Services School & 5 SA Infantry Ladysmith, Etale & Oshikango

(1976 - 1977)

Convoy of Bedfords at Boschoek near Ladysmith.

Call-Up

I was called up to Services School for Basics, not too far from home at Voortrekkerhoogte. My brother had been to the army before me and had a keen interest in military things. I was dropped off at Milner Park and the train from Johannesburg left from some railway platforms in a valley behind the Rand Easter Showgrounds. I didn't know anyone on the train but had brought a pack of cards. We played cards most of the way and got to our destination in the early afternoon.

Services School, Voortrekkerhoogte

We were issued trommels (trunks) and blankets, and told to just find a bed anywhere. We'd be allocated to companies the next day. At this stage it was a bit like a holiday camp, we were thinking the army wasn't so bad. Next day companies were allocated along educational standard, with A and B remaining in camp while C company was sent out to Elandsfontein, a remote place where the bungalows had no windows.

I was allocated to Bungalow 1642, and a number of beds were left empty for the arrival of the Cape Town contingent. A day or two later, late at night a train whistle blew and an hour later they filed in. There were four married men in the bungalow and they each had their own little room in one of the corners. The bungalow was an old brick structure that accommodated about 30, with a long verandah along the front. We walked across to SAMS ("medics") for our medical tests - it was a relief to find out that all the schooldays rumours about "tapping your balls with a teaspoon" were false. The group was 70% Afrikaans speaking, 30% English (including one guy who grew up in England and couldn't understand Afrikaans at all). About half were from the Cape, the rest from around the Transvaal.

The platoon was then ready to start basics. We met our corporal - a real crosspatch who never smiled. When the training began it was a huge shock - how did life suddenly get this horrible? Not only that, but it was going to go on for a full year. The even bigger shock was PT - the objective seemed to be torture and humiliation rather than actual physical fitness. The hour of PT went past very slowly. There was full-on verbal abuse and in return some pathetic whining from amongst the victims. At one PT session I went and stood at the side of the field for 10 minutes or so. Nobody questioned me, and it gave me a brief break to recover some strength. However such chances could only be taken once in a while.

Worst of all was pole PT - a huge telegraph pole had to be lifted and carried by 4 people. Just to stand and hold the thing on my shoulder made my heart beat loudly and I started to feel faint. It was also hard to share the load across 4 people - inevitably the taller ones ended up with the load. Some of the very loud mouths - those that were so excited to be in the army, were going to be officers, might even join PF - became very quiet as the reality of army life set in. There was a rush to the telephones by some to see if some doctor somewhere could uncover a dark medical secret, enabling a reclassification away from G1K1. We had to run in formation every afternoon around the streets, and after a few weeks had a route march out to Elandsfontein (30 km).

The rumour during school days had been that the army would tip copper sulphate into the coffee to deaden all sexual desires. Apparently there was indeed an additive, but it wasn't copper sulphate - whatever it was, it was indeed potent. We were focused on the more base needs of food (will today's punishment finish before the mess hall closes?) and shelter (can I sleep on this bed and still have it ready for inspection?). Sex was a far away concept, and in fact on an icy Voortrekkerhoogte winter's morning, a hot cup of coffee was far more useful than an inconvenient erection.

At one point there was a big meeting called on the parade ground. Some unfortunate guy was marched in for sentencing, he was off to DB (Detention Barracks) - his crime was hitching on the highway. This gave us a sick feeling as he was just being used as a victim - national servicemen hitched on the highway every day. It showed us what a temperamental hierarchy we were dealing with.

One day the wrath of the instructors was really let loose - there was some misunderstanding and they thought that they had been insulted. There was a huge straf (punishment) PT session from mid afternoon and into the night. During the very first minute I ducked behind a wall and disappeared - this was known as a "gyppo". I was able to have dinner and read some Car magazines in the library, before rejoining the platoon for roll call that night. The whole time I was in fear of what the consequences would be if I was found out - in fact I wished I was doing the straf PT. If my gyppo was detected I could be severely punished, or worse the whole bungalow could be punished on my behalf. Once I realised I had gotten away with it, there was a feeling of great satisfaction for outsmarting the system. This and the one PT session were the only occasions when I recall getting out of anything. One guy in the next bungalow had apparently been living with a 25-year old woman before reporting for army duty. She used to drive him around and pay for things. Even more impressive, he didn't talk about this himself but another guy who was his school friend told us - so this story had real credibility. And 25 was really mature - not quite as old as your mom, but getting there. The idea of a chauffeur, bank manager and Penthouse Pet all rolled into one made us realize that the army was seriously wasting this guy's precious time.

We were paid for our time in national service - I think the rate was about 37c per day. This would be left to mount up (took a while at that rate!) and would be paid out at random intervals. Maybe something was deducted to pay for haircuts, I'm not sure but I seem to remember this. The food was good but very predictable and there was no shortage. I don't remember any canteen in Services School but there may have been one. I met up with some guys from the Cape and we became a group of good friends. There were always lots of jokes and laughter at the expense of the army, our instructors and our fellow troops.

We were told that our week at Rashoop was planned to be the worst week of our lives - there even the slackest of "rowers" (recruits) was going to be beaten into shape. We were loaded into Bedfords and driven out beyond Brits, to a forsaken camp in the bush near the settlement of Rashoop. We joked that it translated as "the hope of our race". It was a Saturday when we got there. We each had to pair up with another guy and pitch tents made out of two canvas sheets. I remember on the Sunday we were joking around a lot with bogus army commands ("vir inspeksie, vou kombers") ["for inspection fold blanket". It's based on "for inspection present arms" - a command that led to a four or five stage convoluted process that all us poor dom troepe struggled to get right!!] while from the other tents came the sullen looks of other rowers.

On Monday morning, the jokes were over, the instructors were in a foul mood and the training was full-on - leopard crawling, running up and down the embankment behind the shooting range, and a route march from 25km out of town. We did shooting during that week, I had prior experience and my score was quite good (this point relevant later). The toilets at Rashoop comprised a long board with several holes all in a row, open to each other with no privacy at all. The secret was to wait for nightfall when the flies were asleep and the procedure was less visible. Finally the week came to an end and we went back to the camp. The bungalow seemed like some sort of luxury after Rashoop.

On our return, the sergeant downed a bottle of whisky (or most thereof) and called us together to deliver his great speech, "Basies is Oor" (Basics is Over). Despite his drunken difficulty in pronouncing his words, this speech was music to our ears and we hung on his every word. I'd say it was one of the greatest speeches I'd ever heard. Monday morning we discovered that sadly most of the instructors had missed out on this captivating delivery. A few troops tried to bring them up to speed - strangely this was not appreciated at all. Basics was anything but over. In fact if anything it had moved up a notch and was worse than ever. I think Services School had the approach of ensuring Basics was really tough, as the troops were expected to become filing clerks, storemen and cooks - so would have an easier nine months ahead of them. The logic was that a full year of torture needed to be fitted into the first three months.

We got one pass from Services School - it might have included an extra day I think, because a lot of guys flew back to Cape Town. I had actually been home for dinner once during basics - there was a weekday evening when we were allowed out to church. I met my parents in the carpark and they took me home for about an hour, and dropped me back at the church. It was really enjoyable to have outsmarted the system - might not have been such fun if the car had broken down though. On Sundays sometimes, my friends and my brother would drive out to Voortrekkerhoogte and park at the church, and I would sit in the car and talk to them. They always brought some food as people in the army are always hungry.

As the end of basics approached, those who volunteered for specific roles (JL's, PTI's etc) were allocated to their new units, while all the schoolteachers were packed off to Oudshoorn. The rest of A Company were transferred to Infantry - about 30 of us had the objective to stick together, and we were sent to 5SAI at Ladysmith, by train.

5SAI Ladysmith

The camp at Ladysmith was an architectural disappointment - ancient bungalows made out of boards, unpaved roads - it looked like surplus premises from before World War II. Even worse, as we were marched to our destination we went through the camp, out the other side and down the hill to a remote hangar. This was C Company, made up of three sections 7, 8 and 9.

The nearest facilities (toilets and showers) were about half a kilometre away up the hill. There was an enclosure of "piss buckets" near the hangar. Meals were fetched from the mess in a jeep and served in the hangar. We got to 5SAI just before school holidays started, so in the distance were the cars of holidaymakers heading down the N3 highway to the beach, just to add to our desperation and mental torture.

It was evident to the Sgt Major that the group from Services School were very good at drill. Life settled into a harsh routine with each day starting with the "two comma four" - running 2,4 km in under 12 minutes, and if this was not achieved it would need to be run again. This was done in the dark before sunrise, usually around 5 a.m.

Playing cards during 'hurry up and wait" time.

The emphasis at Ladysmith was more about fitness than presentation for inspection. I remember one day the Sgt Major told us that Jody Scheckter (a famous racing driver) would be visiting us, and we were to be on our best behaviour. I was excited to think that now we were in the Infantry, we would be getting visits from celebrities and national heroes. To our horror "Jody Scheckter" turned out to be "waentjie PT" - pulling a very heavy cart (intended to be towed by a Bedford) around the base. I remember that when I was rotated into the front position at the "V" of the wagon, my heart started to beat audibly and I almost passed out. Jody Scheckter made many unwelcome visits from then on - but never in person!

Pole PT was not as bad as at Services School - the poles were smaller and it was two to a pole, so at least each person only carried 50% of the weight. We covered great distances with the poles - across the river at the base of the camp, and up the hill across the road from the main entrance gates. During lectures there would often be the command "om die magazyn" [Around the magazine]- we'd have to drop our books and run down to the magazine at the edge of the camp, and back again. The last third back would be intercepted and sent again. A 5SAI speciality was "skaapdra" (carrying like a sheep). I had a skaapdra partner who was quite big but was amazingly light as a feather.

The hangar, where C Company lived during national service.

Another frequent activity was night PT. The hangar was far from the main camp and was therefore largely unsupervised - the instructors could do virtually what they wanted. A whistle would blow in the middle of the night and if everyone was not out of the hangar on the count of 10 (which of course was impossible) then we had to carry our trommels around a pole in the parade ground. This would be repeated and varied over the next hour or so. After a while some guys would lose all dignity and start to beg for mercy.

Rifleman M. Senior and the bungalows of Ladysmith.

Finally after some months there was the possibility of one weekend pass. Initially this was to be for everyone, then the rules started to change and the pass depended on the time taken in the 2,4 km. Almost everyone cleared that hurdle and on the Friday when the pass was to be issued, we ran to the shooting range. The shooting scores were recorded, then once we had made the return run back to camp, we were told that only the highest scores had earned a pass. Those going on pass were all those who had been at 5SAI for Basics - because they understood that it was necessary to bribe the guy in the "skietgat" who was marking the score. So we had some excellent marksmen who even earned a golden "baltjie" (badge) for shooting excellence - they were the ones who had paid the skietgat well.

Among the punishments was one called "Liter Liefde". The objective was to drink a litre of water, do straf PT, drink another litre, more PT and so on, until people were throwing up for the entertainment of the instructors. One morning it was decided my inspection was not up to scratch, I was a "slegte" (bad guy) and I was told to "klim in die bus" (join the punishment squad). To the lieutenant's disappointment I was able to down every litre and not vomit. I was left out of Liter Liefde after that as I spoiled the fun. There was a trampoline in the centre of the hangar for the outworking of any remaining energy at the end of the day. One guy used to trampoline frequently wearing nothing but a pair of army socks. I'm not sure whether the constant bungy-jumping of his genitals would have done him any harm, but I doubt that it was much of a health tonic.

Graham preparing for river crossing training.

We had to spend a week at Boschoek, located north of Ladysmith on the road to Standerton. It was a large piece of land with the Biggarsberg mountain as a backdrop. All gunfire was to be directed towards the mountain. We had to dig into trenches, and could not move around freely in daylight in case of being seen by an imaginary enemy. After dark we could go up the hill through a graveyard to get food. At night there were patrols to find and identify checkpoints and features in the landscape. Boschoek was meant to be uninhabited but I remember one time at about 3 a.m. we ducked down behind an embankment and a human figure walked past. In the lap of the mountain was a small abandoned village. On daytime manouvres, always after scaling some hill, leopard crawling in a fire-and movement exercise, or on a route march, at morning tea time no matter what the terrain, a Bedford with a tea urn would appear.

At around that time a member of the company wrote to a magazine called "Armed Forces" - they usually wrote about mercenaries, new weapons etc. - and as a result a journalist arrived to investigate C Company. The contact had been anonymous and many people thought I had written it. The journalist wrote an article and took a number of photos - he focussed on our section (Section 8) as that was where his contact was from. The journalist took the rifleman out to dinner in Ladysmith as a reward.

Our section had a PF corporal, who was so "kop-toe" (keen) that he got his own Citroen sprayed in a military green colour. He liked to fire canisters of teargas at us after a long run. When he lost his temper (which was several times per hour) he would be unable to speak anything further than "fffffff.." - even his favourite word he could not utter. His eyes would flicker open and shut and his eyeballs would roll back into his head. The rumour was that both his parents were brain surgeons in Durban, and that they had used him in some bizarre experiment. I'd wake up in the morning and think, why is this man in control of my life?

We had a Portuguese major, a guy tried and tested in the liberation war for Mozambique. It was rumoured he'd killed many people and didn't care if he added a few more to his tally - especially a couple of "dom troepe" (stupid troops). We had to jump off moving Bedfords - regulation speed for this exercise was 25 km/h but the corporals were laughing and had a mad look in their eyes, and through the back window we could see the needle hovering at 40. Anyone who was hesitant would be killed or injured, we had to run full speed to hit the ground standing. Amazingly nobody was hurt. We heard that B Company was not so lucky and on one of their exercises at Boschoek a Bedford rolled and someone was killed.

We were sent home on a 7-day pass. With so few passes during the year it was strange to be out of the army for a while. The army seemed to widen the gender gap in South Africa. I remember going to a party and being lectured by a girl my age, about how it was necessary for guys to go to the army, that it was character building, that wimps were turned into men, and so on. I thought how easy it was for this spoilt upstart to say when she had no concept of the suffering in the army. She had the superiority and smug satisfaction that she was unaffected by the call-up. From that day onwards I saw the merits of Israel's system, where the girls were called up too. On the train back to Ladysmith, one of the guys in my compartment was a fairly stocky and aggressive troep who decided to go to the lounge car to try his luck. He met a girl and they agreed that at the end of the evening they were going to go back to her compartment and “put it” (exact quote). I think her idea of the end of evening was intended to keep her options open, and sure enough a better offer came along in the form of another 5SAI rifleman, taller and better looking. So she decided to trade in the first guy on this more upmarket character. The first guy however was not giving up that easily and started a fight, getting them both thrown out of the lounge car. The fight continued in the passageway outside our compartment - a feat in itself as swinging a punch in that confined space was no easy task. The girl meanwhile realized that these two guys were now fully focused on each other, and shuffled back to her compartment to sleep off whatever alcoholic beverage had made either of these “vuilgatte” (deadbeats) seem in any way desirable in the first place.

Graham standing near the big pink gates, 5SAI Ladysmith.

Back in camp, on Christmas Day we were allowed to buy a few beers after church and sit near the swimming pool behind the canteen. There was no jeep collection for food and we had to eat in the mess hall. One of the guys - the company clerk - miscalculated his tolerance for beer and during lunch his face flopped down straight into his meal. He passed out and had to be carried down to the hangar to sleep it off. Actually in this case the words "straight" and "company clerk" don't belong in the same sentence.

The Border

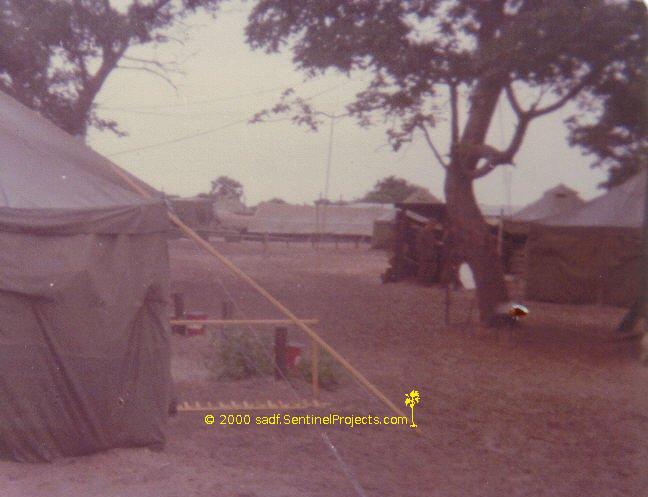

Etale, 18km south of the border crossing at Oshikango.

The day arrived to set off for the border - 3 days by rail to Grootfontein, and then onto Bedfords for the rest of the way. The Owamboland countryside looked like a heavily populated garden situated on a vast flat beach of sand. Our base was Etale, 18km south of the disused border crossing at Oshikango.

Oshikango was the border post on the main road north to Angola.

The rumour was that Etale had been attacked in the recent past. Each week all but one of the companies or sections would be sent out on patrol. Our first patrol was to a place called St Mary's - there was an old hospital that had been destroyed by mortars, just south of the Yati Strip (the 1km wide no-go zone) at that point. We were tense that first day patrolling the border and sure enough before long a shot rang out. We jumped from the unimogs (vehicles) and crawled under cover - but it turned out to have been an accidental shot fired by the unit's own Rambo. He spent a few days running around with sandbags on his shoulders after that, and became a far more humble human being.

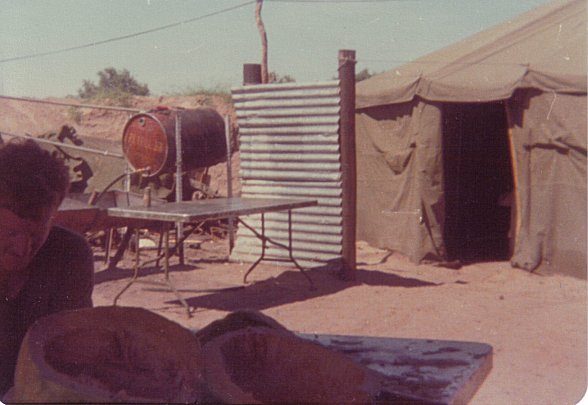

There was a canteen in the camp at Etale, which had been dug out and built underground. One day there was a rainstorm and the canteen was turned into a sea of brown water, with Tex bars and Castle Lagers bobbing on the surface. They built a new canteen after that.

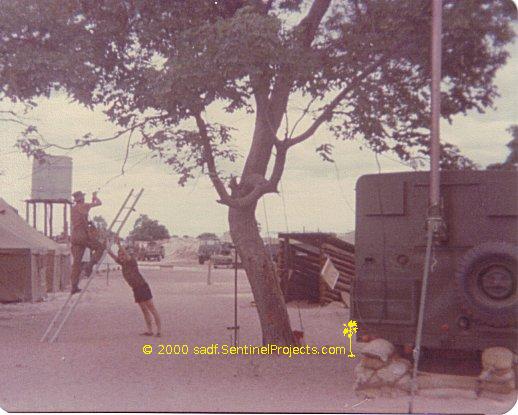

The canteen picture (which also has an NCO on a ladder fixing an aerial wire, while a dom troep holds the ladder) shows the entrance to the underground canteen. It is this canteen that filled with water during a downpour.

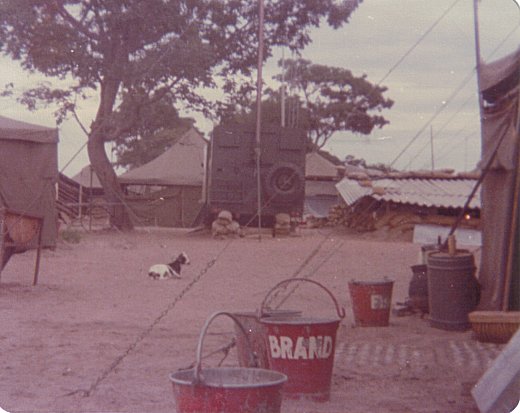

The kitchen scene shows one of the cooks at work (on a pumpkin it seems) while the goat photo (I think it was a sort of pet) shows one of those trucks in the background, maybe a generator truck or a mobile comms post - not sure.

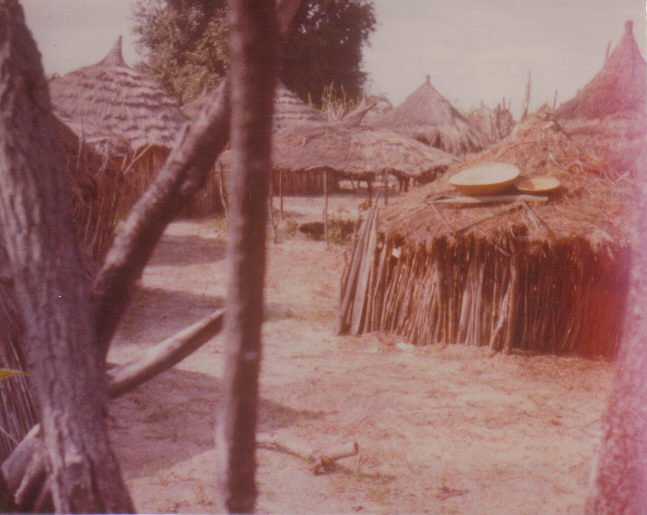

An Owambo kraal visited whilst on patrol.

Back in Etale, the major had a huge problem on his mind. The 5SAI radar unit had been set up in the Yati Strip just west of Oshikango, and it was picking up a large number of troop movements across the border. The major contacted Military Intelligence, and one morning a convoy of Bedfords took the high-ranking luminaries out to the radar station. After much investigation it turned out that the radar unit had been set up to face the wrong direction, and the troop movements being monitored were the vehicles moving in and out of Etale.

We were told that the staff sergeant had "gone to the States". I was greatly impressed, and envisaged him travelling across New York harbour on the Staten Island ferry, or consulting some of President Carter's military luminaries at the Pentagon. I was troubled though to think that a halfwit should have been sent to the USA to represent his country. It was later that I found out that when in Owamboland, "the States" referred to South Africa.

Unimogs patrolling the Yati fence near Miami, about 30km east of Oshikango.

We went on several patrols west of Oshikango, often through wide patches of water that was thigh-deep. It was the rainy season and often the tents were inadequate and everything was drenched. Our brief was to befriend the local population and one time at a kraal we had to drink a sour home brew with a couple of dead "miggies" (tiny insects) floating on the surface. Later, east of Oshikango, we were lying in formation one night and the person on guard duty fell asleep. In the morning there were tracks through the middle of the formation with a shred of light blue wool on the Yati fence. The lieutenant was devastated as he wanted the credit of a "kill" to his name. Around the same time another section got a kill and buried the body in the Yati with a headstone of "Vasbyt" - people would point and laugh with no regard to the fact that it was someone's grave.

The final month on the border was spent at a camp called Miami. By now the PF's were getting careless and one night they had our section of Yati overlapping with another section, by 2 kilometres. Fortunately the two patrols never met up in the dark that night. Our time at Miami was quite relaxed and the day came when the next company (a group of campers) took over. We were later told that a few weeks after we left, Miami came under heavy mortar fire with several casualties.

Back to Ladysmith

On the way back to Ladysmith, the rumour was that when we got there our time would be extended beyond 12 months. Everyone was depressed, and sure enough a few days later the whole of 5SAI was called together for a meeting in the hall. Dreading the worst, everyone sat in silence. Then the purpose of the meeting was announced - did we think that bottled beer or beer on tap would be more suitable for the new mess? We were disbelieving that a meeting would be called for such a trivial question - the relief was huge and the noise level rose to the point where they abandoned the meeting.

The last few weeks at 5SAI were a bit like being at a country club. There was no forced exercise, lots of instructional movies, beers in the evenings on the verandah of the new mess, and a couple of days spent burning firebreaks at Boschoek. The only problem in life was that we were on guard duty every second night. It was so cold that it was not possible to warm up between shifts - so effectively a guard duty night was a sleepless night.

About this time people started parking their cars on the parade ground ready to go home. There were rows of brand new cars - I later found out that the railways (employer of most of the company) had kept paying their employees during their army service - so there was a lump sum ready to spend on a car. The man's car was the Datsun 120Y, while the truly macho went for the Mazda RX2, which normally manifested itself in a burnt orange or a lime green. Those that were not already employed had definite plans for their lives at the end of that year - they had wasted enough time.

Returning to Civvy Life

The day that I drove out through the big pink gates at Ladysmith was a high point in life. A few days later I was back at work, with the new habit of "strekking" (standing to attention) for the boss. It was hard to settle down and for some months I had nightmares. I was advised that I had been posted to Johannesburg Regiment, and I received call-up papers for a camp the following year. As I was at university part time the call-up was deferred, and in fact I never went back to the army again. I graduated in May 1980 and moved jobs a month later, to a position in Sydney Australia. I sent a polite note to the regiment to advise them of my change of address, just in case I fell into their clutches again in the future.

The most memorable thing about the army was definitely the good friendships made. The ways that the army changed me - it made me enjoy exercise, it instilled a habit of getting up early, and it made sure that I will never voluntarily go on any camping holiday!

Published: 12 August 2004.

Here is a shortcut back to Sentinel Projects Home Page.