CHAPTER THREE

THE AG COMPLEX

THE MEDICAL SECTION OF SECTOR 10

COMMANDANT JAN POTGIETER

The Officer Commanding the Medical Section of Sector 10 (Pronounced 'one zero' and not 'ten') was Commandant Jan Potgieter. Marius had told me about him; that he was a 'bit of a Nazi', but fine otherwise. He looked the part, a stocky blond Aryan.

He wasn't there when I first arrived, and he would often disappear suddenly for a couple of days to go hunting. He lived in Oshakati with his wife and little identical twin daughters. Major Kevin Holmes, in satirical mood, suggested that with the girls being twins, the Commandant only found it necessary to have the photograph of one of them on his desk. His house had been damaged in at least two different revs.

His favourite topic was that his medical section was the only operational medical section in the world. He was clear about that - 'the world', not just on the border, or in southern Africa. No-one dared challenge him with the possibility of similar medical commands existing in Israel (Don't mention Jews to the Commandant!), or that the Russians might have something similar in Afghanistan. He stated proudly that anyone injured in the Sector could be sent to 1 Military Hospital in less than two hours, and again no one queried this. He believed that this knowledge of how well looked after the injured would be spurred soldiers on to brave acts - the only problem was that with the sector arranged the way it was, there were precious few opportunities for soldiers to commit brave acts.

The Commandant was a law unto himself; he would sit in his office late into evenings, but no-one was sure what he did. He had a short temper, and would flare up easily, but in fairness, he would soon calm down again, and the provocation would most likely be forgotten. He protested that he was not anti-Semitic (`I just don't like Jews!') but he always had a point to raise about complaints made by some Jewish Rabbi, who had said that the Jews 'could not forget and could not forgive'. "What right does anyone have to say that they cannot forgive and forget?" the Commandant demanded of those who knew that it was a rhetorical question. Had he not forgiven and forgotten the way that the British had put crushed class in the porridge given to his ancestors in the concentration camps during the Anglo-Boer War? (Not really!)

The Commandant had originally trained as a dentist, yet as the OC of a Medical Section, he was in charge of doctors. This was to be a continual source of conflict.

I actually liked Commandant Potgieter very much, and he was always very decent with me. I was careful not to cause offence, and I outwardly agreed with everything he said.

He would never be without his military issue radio, and he commented at some stage that he was always pleased when people called him using it to report developments. I heard him say this several times, and I was never sure whether he meant this at face value, or whether he was being ironic, and wanted the staff on duty to be sort out minor events without troubling him. On reflection, he probably did mean it at face value.

The Medical Section at Sector 10 consisted of:

(a) A doctor and one or two Ops. Medics (Militarily trained paramedics) posted to each camp or outpost.

(b) A Military Base Hospital (MBH) at Ondangwa Air Force Base; specialising in surgery; to deal with surgery cases likely to be 'casevaced' down to `the States'. This was most often staffed by consultant surgeons called up specifically for two week camps. The OC of the MBH was Major Roland Berry, whose beautiful wife was a social worker in the sector.

One surgeon, called up for a two week camp, applied for permission to fly up in his own aircraft, but this was denied, so he drove all the way (normally a four day drive) in his sports car. The man had style! - and money!

(c) There was a Sickbay at Oshakati, in the Headquarters camp, twenty metres away from the Protea Officers' Mess. This was staffed mostly by national service doctors doing three month rotations. Those lucky enough to remain in Oshakati rather than be posted out to 'the sticks' usually had special skills in internal medicine. The doctors when I arrived were David Dix, Conrad Smith, Basil Abromowitz and `Sakkie' Loftus. The Sickbay was open to all soldiers of Oshakati, the local police (including Koevoet) and the local white civilian population.

Military personnel had initially also worked at the State Hospital at Oshakati, but they were asked to leave by the Owambo administration. Do these people really want us here? Not according to the evidence ...

There was a Major 'Cubby' Van Rooyen, a doctor, but doing 'Operation Work' - whatever that meant. He was the person that the SWAPOL and Koevoet always asked to see.

The OC of the Oshakati Sickbay was Major Kevin Holmes. Kevin was an unlikely person to find in the permanent force. He appeared to be very British, having studied at the University of Cape Town before studying medicine through the Defence Force (He had been a 'Mildent'). He had been the OC of the Oshakati Sickbay for two years. He apparently had responsibility for doing any autopsies which were necessary, and also seemed to have responsibility for doing the baby clinic. He had a slight build, was always neat and smart, and had an immaculate small moustache.

He lived on his own in a caravan, and lead a rather isolated existence. He was staunchly tea total, about which he was teased when we persuaded him to come out with us. He had the capacity to mix well when he chose to and had a good sense of humour. He remained a pleasant but enigmatic figure throughout the time I knew him.

He hosted a barbecue at his caravan one evening for the medical staff, at which I learned more about him. He had a large collection of tapes of church services which his parents recorded for him at the church that he had attended in South Africa, and which they had posted on to him.

Kevin was rumoured to have had disciplinary problems with some of his troops before I had arrived. Apparently they had done as they pleased, unchecked, and had called him by his first name. Kevin was a very careful fence sitter - he seldom took a stand on anything, and with the Commandant usually in very close proximity, he appeared seldom to need to. The psychologists needed Kevin's agreement with our decisions to refer patients down to 1 Mil, and he accepted our judgement that they needed to go. That was good!

I enjoyed a playful antagonistic relationship with him, and I would always honour him with 'my best salute' when I first encountered him each day. He always looked slightly pained as he returned my salute, and he probably wished that I wouldn't do this.

Kevin told of Pieter Griesel having done a border tour, and told of him living in the Protea Officers' Quarters and tormenting a dominee who lived to the room next door to him, by whispering pseudo 'Satanic' or 'Divine' messages to the dominee through the walls.

THE AG COMPLEX: HEADQUARTERS OF SECTOR 10 MEDICAL COMMAND

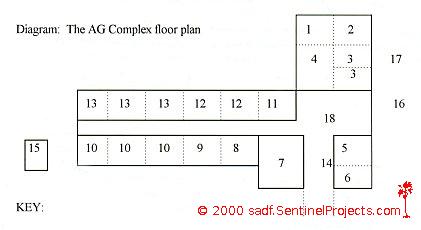

Diagram: The AG Complex floor plan 1 2

KEY:

|

1. My office |

2. Baby Clinic room |

|

3. Extra office |

4. Sister Bertha Syman's office |

|

5. Commandant Potgieter's Office |

6. Ops. Room |

|

7. Tea Room & switchboard |

8. Charl's office |

|

9. Psychology play room |

10. Dentists clinical rooms |

|

11. Toilets |

12. Admin. offices |

|

13. Health inspector offices |

14. Papier-mache elephant |

|

15. Storage shed |

16. Flag pole |

|

17. Parking area |

18. Entrance mall |

The AG Complex was about two kilometres from the Headquarters complex where the Officers, NCOs and Privates lived. (I never found out what 'AG' stood for!) To get there each working day, the staff met at half past seven and piled into an army van, and a duty driver would drive us there. `Breakfast' was not part of the routine. We would be driven back to the mess at 10 am, for 'brunch' and then back to the AG complex for 11, where we would remain until the end of the working day at half past five. We were expected to work from 08H00 - 10H00, 10H45 - 12H00 every second Saturday; which was a good time to see children who would be at school during the week. We (officers) were allowed to wear civilian clothing on these Saturdays. It was implicit that, although the psychologists had designated `office hours', we could be required to do out of hours work if necessary. For this reason, the psychologists were not given duty officer duties.

The Regimental Sergeant Major of the Medical Section of Sector 10 was not there when I arrived, but I met him about a week later. He was a 'drunken old sod', and when I first met him he was sporting a magnificent black eye, apparently from having been in a fist fight from which he had emerged the loser. He did not possess the bellowing voice and high blood pressure one associates with an RSM, and if he had ever had it, he had lost it - possibly burned out. He was a mild and relatively nice person under all the military crap, though possibly I had this impression because I was an officer and had nothing to fear from him.

When given a chance he could talk of interesting things, and I enjoyed hearing him talk on the history of the development of helmets from WWI to the present day. He had his moments!

A rumour that I think could be traced directly back to him was that he was going to be transferred to be the RSM of the SAMS College, which would be surprising, because the place was probably the SAMS' showpiece. He had no initiative whatsoever, and when you asked him to arrange something, he would tell you that it couldn't be done, and then rack his brains to try to think why not, before coming up with '... because it had not been done before.'

I found communication to be one of the biggest difficulties in trying to work in Sector 10: "1987/08/10. A major frustration in my life at the moment is difficulty in making telephone calls - not to the Republic (which one would expect to be difficult), but in the small town of Oshakati. Most of the people I wish to contact are within two kilometres from where I work (the AG Complex). The calls involve arranging appointments, or trying to get collateral information from social workers on people at the units. Difficulties encountered lead one to contemplate returning to the tried and trusted method of using a runner with a cleft stick.

"To make a call, one first has to find the local switchboard operator, a disinterested national serviceman called Victor (Victim?) Dewey. He was trained as a radio operator, which is where his interests actually lie, but he is used as a switchboard operator, while we have no permanent radio operator.

Step 1: Find Victor. First one has to find Victor. He is seldom to be found manning the switchboard, and is more often to be found talking to his ghostly friends on the radio network. He could also be adjusting aerials on the roof of the building, or he could be anywhere else.

Step Two: Persuade Victor to return to the switchboard and to try to place your call. Now the other eight or ten people who work in the complex see that you have found Victor, and they congregate around him to get him to put through calls which they remember they should make, some of which they are convinced are more important than the call for which I have hunted Victor down.

Step Three: Then Victor has to try to get through to another switchboard; either the town switchboard, or else the military one. Should any call whatsoever 'come in' at this time, Victor tells us that an incoming call overrides all outgoing calls, and there's nothing he can do about it. So you lay siege around Victor, making sure that he doesn't flit off while the incoming call is being dealt with.

Then its your call again, and the central switchboard is not available - Victor tells you that the line is busy. So you besiege him still, getting him to repeat the procedure. At last, via the central exchange, you get through to the unit exchange, where, if anyone answers, the person you want is not there right now, and you leave a message asking them to phone you back, which they never do."

Victor would try to make any call by radio if at all possible, and shout; 'One Zero, One Zero, One Zero, One One' into the static. When dealing with an incoming call, he will far rather debate the probability of a person not being in his office, than actually go and look.

Drivers say that whenever one of them is taking a Rinkhals through to Ondangwa, Victor is always on-board pining for them to start the engine so that he can start to play with the radio. If the radio is being used when the engine is started, the radio gets 'blown'.

To make matters even worse, Victor had a stutter, which deteriorated when he was under stress. A military switchboard operator with a stutter! - a coincidence one would not believe if I had not met him in real life. Victor had to bear the brunt of the Commandant's ranting and raving when he could not put a call through, at which stage his attempts at speech were indecipherable.

Victor told me about the battered papier-mache elephant which remained at the AG Complex throughout my stay. It apparently belonged to the Oshakati nursery school, and had been damaged at a fete or some such activity. Someone who managed to represent the medics had volunteered the services of the medics to repair it for them. Koevoet or SWAPOL members overheard this, and they got stuck into it, damaging it further because the medics had volunteered to fix it. So they have a sense of humour - of sorts? And so it remained, awaiting repair.

THE HEALTH INSPECTORS

There were three different health inspectors based at the AG Complex. Their profession earned them the nickname 'fly spies' throughout the defence force, and probably further. The other nickname, `drain surgeons' was not used as commonly. The health inspectors had to inspect hygiene conditions in the various bases in the sector, inspect food, and spray uncured wooded statuettes taken back to the 'States' to certify that they were free of disease.

Captain Dirk Cloete was the head of the department, and he had been a civilian for a number of years working in the Transkei before joining the SAMS and being sent, with his young family, up to Sector 10. Dirk was a straight-forward and good man.

He had a national serviceman health inspector to help him. National service health inspectors were resented amongst the medical service officers - the bulk of the SAMS officers were professional graduates, except for the administrative and some of the operations personnel, who had all done the `blood, sweat & tears' Junior Leaders officers course. Graduates in subjects like micro- biology became corporals if they were lucky, whereas health inspectors with a three year diploma

(Philip Christiansen, who was a health inspector in Sector 10 while I was there corrects me thus: '[Health Inspectors] must have a three year National Diploma in Public Health - the equivalent of a bachelor's degree. However, we Health Inspectors were one of the least qualified officers in SAMS in terms of years study. I never let that worry me, though!") were Lieutenants along with doctors and dentists. It was probably just snobbery on our part.Because of the perceived nature of their work, SAMS health inspectors had vehicles made available to them, and they appeared not to have to answer for what they used them for. The NSM fly spy was given an almost brand new Toyota 4x4 bakkie (pickup with canopy), which he appeared to be allowed to do with as he pleased. Doctors, dentists, and psychologists had to walk around, or humbly beg lifts - at times from him.

The health inspectors did not seem to have much work to do, and appeared to spend most of their time in Dirk's office, staring at each other.

I chatted with Dirk about how we could arrange for fathers to appear to be rescuing heroes to impressionable young children. A stooge could stage a kidnapping the child, and the father could then burst in, and smite the kidnapper (carefully) on the pro- offered chin. Blood then trickles from the kidnapper's mouth as he slumps senseless against a wall. The father then picks up the child and strides away, holding the child firmly in his arms. Repeat once a month.

One of the functions performed by the health inspectors was to condemn 'rat packs' which had passed their expiry date. They did this in the store room at the back of the AG Complex, and we were invited to help ourselves to the crystallised fruit, energy bars, puddings, and everything else which was unlikely to be unfit for consumption. There were lots of fun foods in a rat pack, providing that one did not have to live on them for weeks at a time.

Also in the Health Inspector's department was an Owambo soldier called Petito. He had the title of 'Assistant Health Inspector', and we had no idea what he did with himself all the time. He lived in the house he was born in, and was paid more than R 800 per month - and danger pay. (That makes it more than three times what white national servicemen, like the dental assistants, who worked in the same building, under military discipline, were earning.) He had been awarded the Pro Patria medal for his efforts to `combat terrorism'. He kept a very low profile, and was most often found speaking to his wife on the telephone, and occupying the lines that the rest of us were waiting to use.

He survived because he was the Commandant's pet. I mean that literally. The Commandant saw him as a special project; like a wild animal that he was taming and domesticating. I think that this was a reasonably accurate description of their relationship.

Petito arrived at work one day unshaved - probably a couple of days growth. I shat on him - outraged at the injustice of what would have happened if one of the national servicemen had done so. He answered back, and tried to walk off, and just then the Commandant arrived, and asked what was going on. I reported what I was disciplining Petito about, and the Commandant took me into his office and gave me a father and son talk about how we cannot expect the same standards from these people than we can from our own kind. (Whites as opposed to blacks.) He might have told Petito to go and shave, but I don't remember it. But remember, this man is getting paid three times what South African national servicemen are being paid - supposedly to protect his own people!

At one stage, the RSM called a meeting of all the junior officers and demanded that we enforce military discipline amongst the soldiers that we worked with; 'You are soldiers first, and doctors/dentists/psychologists second.' I pointed out the hypocrisy of Petito getting away with murder, sanctioned by the Commandant, and the RSM looked sad, and said that Petito was 'unfortunately' a special case. It was impossible for him to tell us to set an example and discipline our men when the Commandant as the OC undermined the fundamental work of the RSM. And things like that happened so often!

ADMINISTRATIVE PERSONNEL

There was a administrative NCO, Sergeant Major (WO2) Venter. I automatically spoke to him in Afrikaans, returning the compliment he had paid me by speaking to me in English. It was only when one of the other staff told me that he had been light-heartedly offended by me speaking to him in Afrikaans all the time that I learned that he was actually English speaking. There was apparently no love lost between him and the RSM.

There was a civilian woman, wife of a military person, also English speaking, who was the senior Administrative Clerk. There was another English speaking civilian woman who was responsible for transport arrangements - she was always decent to me, even if over familiar, but was shunned by just about everyone else because of her socially inappropriate (embarrassing) behaviour when she was out socially. She was very loud, and apparently attended some semi-official function in a very tarty outfit. Lastly we had a typist, who was Afrikaans speaking. She had a serious row with her husband one night, got in the car and drove back to the 'States'. We never saw her again. When I arrived at the sector we had a typist and a photocopier. When I left we had neither, and I was sending out carbon copies of hand written reports.

OPERATIONS PERSONNEL

The Commandant was in charge of Medical Ops. in the sector, assisted by Major 'Cubby' Van Rooyen. There was also a permanent force Lieutenant Niewoudt, a woman who had trained as a nurse, who doubled as the receptionist for the dentists. This created a bizarre situation for her, as a PF, outranking people who out-qualified her, and on whom the service depended, and this lead to a brand new set of conflicts.

There were also young ops. Lieutenants, school leavers who had done the 'blood sweat and tears' Junior Leaders officers' course. When I arrived, the young ops. Lieutenant was the son of one of the top Generals of the SAMS, Knobel, if I remember correctly. He left about two weeks after I arrived. I don't think that I had any dealings with him, but apparently he was immune to everyone, no one daring to expect anything of him because of his important father.

He was replaced by Lieutenant ____

(Bryan Abbott remembers his name as `Percy', though he was Afrikaans. That doesn't sound familiar to me.), a very lonely teenager. He was the only school leaver amongst the SAMS Officers. He was eighteen or nineteen, while the rest of us were between twenty four and twenty six. Even the fly spy Lieutenant was a couple of years older than him. Inevitably there was very little for him to do. The medics officers had all cliqued into professional groups, and were not particularly interested in this rather thick teenager. So he did what is understandable, if not militarily acceptable; he started to mix with the troops, who were his own age. But there was conflict within him that he wasn't mature enough to cope with; as an officer he had to keep his distance, but his loneliness demanded company. He would mix with his age group, and then suddenly revert to his role of officer and shit on them for being familiar.They then ignored him, or got back at him. This familiarity with the troops was not much of a problem for the professional officers; we were separated from the troops by our ages, and by our qualifications and experience. Unfortunately, to us, the young ops. Lieutenant stood on the same side of the great divide as the troops. I spoke to him a couple of times, after he had some confrontations with Private Bruce Van Laun, two years older and three times brighter than he was. I asked Bruce, man to man, to leave him alone, and then advised the Lieutenant to try to make friends with the army lieutenants who were more his age, which he might have done. The impression he gave me when I took him into my office, was very much like a school boy expecting to be caned after fighting on the playgrounds. I saw Bruce first so as not to publicly humiliate the Lieutenant.

I felt very sorry for him. He tried so hard to be liked by his brother medics officers, who prayed that he would sit at someone else's table over brunch or supper. He would strike up a conversation about subjects we were not interested in, like military breakthroughs, or military etiquette, while we laughed and joked and cried on each others shoulders about the absurdity of the military, 'M*A*S*H' style!

I was at the duty desk in the sickbay one evening when a call came in saying that a casualty was on his way, having lost an arm in a MVA (Motor vehicle accident). Our teenage ops. Lieutenant - whom I assumed would have known what procedures to follow when something of that kind happened - did not make a valuable contribution. He wandered around for a while with an earnest concerned expression, and a frown furrowing his forehead. "This is terrible," he said. "A man has lost his arm." Then he disappeared, and we didn't see him again until the next day.

I did quite a lot of work that night which I think he was supposed to have done - making radio contact with the OC etc. Towards the end of my tour, the young Lieutenant seemed to have palled up with the other medics officer outcast, the fly spy.

I heard about him later, though. He had apparently gone on holiday to the Etosha nature reserve, got drunk, and then tried to throw his weight around, declaring that he was an officer in the SAMS. I did hear what trouble he got into, but the details escape me.

DENTISTS AT THE AG COMPLEX

There were three dentists working at the AG Complex. Enrico was my room mate. Wilhelm was a good rugby player, and it was an open secret that he lived with a girl in the compound outside of the military base - this would have been officially stopped if it had been officially known about. The third was Mark Allison, who was English speaking. They were each staying at Oshakati for the balance of their initial two years national service, following basics and officers' course. They had volunteered to do so, saying they preferred the stability of the place. If they had elected to stay in the 'States' they would have been likely to have been moved around a lot, and not had the satisfaction of watching their cases develop. It appears that there is more to dentistry than putting fillings in teeth!

Enrico was obviously the best known to me as we shared a room together. Wilhelm was generally arrogant and aggressive, and Mark tended to be his lackey. Enrico was annoyed with Mark, who only mixed with him when Wilhelm was not around. Mark was tall, sleek and sharp-featured. He was a very quiet person, and I only got to know him towards the end of my tour. He had a very subtle sense of humour which he did not waste on just anyone.

Mark drew my attention to a SABC Broadcast featuring Captain Wynand Du Toit, who had been held captive in Angola for a couple of years after having been caught on a reconnaissance mission in 1985. What he said was: 'Toe ek in Angola was ...' ('When I was in Angola ...') which, in the English sub-titles was translated to; 'During my sojourn in Angola ...' Forced literacy!

(Wynand du Toit was released in an exchange of prisoners in the third quarter of 1987. See Soule, Allan, Dixon, Gary & Richards, Rene (1987) The Wynand Du Toit Story)There were two Dental Assistants, both young English speaking national servicemen who volunteered for this job with a view to dentistry as a career. They were Craig Venter and Bruce Van Laun.

The dentists were probably the biggest problem area for the RSM when he tried to impose military discipline on the medical services. The national service dentist Lieutenants worked very close to their assistants physically, and being busy, did so all day. They allowed or encouraged their assistants to call them by their first names, and they tended to socialise together after hours. They would occupy spare time playing darts; this could be when patients did not arrive, or when they were waiting for X-rays to develop, or moulds to harden, or whatever else dentists leave people lying on their backs for hours with their mouths open for.

Familiarity got to such a level that one of the dental assistants made a comment about 'Raw Dutchman', a derogatory reference to Afrikaners. Enrico took offence, and moaned to me about the 'Raw' part. That irritated him most, implying uncivilised, and from the bush, yet he was a dentist, from a prestigious dental school, and with genuine Dutch grandparents.

Once Enrico offered suckers around. I commented on my surprise at this, from him, a dentist. He smiled, and told me that he considers it to be an investment for the future.

A Koevoet Officer's wife was having cavities filled by our dentists. The husband threatened the dentists with violence if she felt any pain. Koevoet were never disciplined, or made to apologise for such objectionable behaviour, thought it was often complained of.

Bruce Van Laun told a magnificently animated story about his and the dentists' attendance of a party with - emphasised throughout on - 'The Right People'. The story consists of much heavy drinking, and getting peckish, the guests frantically looking for food in the fridges, only to find each one packed to overflowing with still more beer. Finally, at around two in the morning, the host announced that they would start to barbecue as soon as the ashes were right. He went away, and Bruce was expecting him to return with the meat to be barbecued, but he returned with a 'fucking big tree' which he cast on to the ashes, which would have to burn through that before the meat could be cooked. Bruce's descriptions of the Ethiopian agonies of the guests was the highlight of this story.

He told this story finally at my request at my farewell party attended by myself, Kevin (the only other PF invited), the national service doctors and dentists and the two dental assistants. The RSM had by now given up hope of separating the dentists and their assistants.

THE SANDWICH STORY

The NSMs and I go to brunch at the mess between ten and eleven each morning. The PFs have tea between 10 and 10.30, and go for lunch supposedly between 12 and 1. PFs pay R5 per month for tea, of which they have more than three cups a day - it is only a token fee. Sandwiches are provided for the morning tea, three loaves worth, amongst about eight people.

Enrico Van Dijk helped himself to a sandwich once, while our transport to brunch was delayed, because another NSM dentist was finishing off with a patient he was working on. The Nursing Sister, Bertha Snyman, pounced on him and told him that he was not allowed sandwiches because he did not pay tea money. There was more than enough for all.

Enrico asked an Adjutant Officer - Lieutenant Smith, (One of the Afrikaans 'Smith's) who lived with us in the mess, whether NSMs were entitled to have some of the sandwiches or not. Lieutenant Smith told him that NSMs were entitled to sandwiches. Next day, Enrico deliberately took another sandwich. My co-psychologist Captain Charl de Wet shat on him this time, but Enrico stood his ground, and said that he was entitled to the sandwich. Charl then reported this to Commandant Potgieter, OC MED SEC 10, who phoned the Commandant in charge of logistics.

We are not sure what the Log OC's reply was, but Enrico was called in to the Commandant and asked, not to discontinue eating sandwiches, but to avoid confrontations with Captain de Wet. Enrico was livid, as the Commandant had sided with another PF rather than for what was right. Charl afterwards approached Enrico and said that some of the fault might actually lie with him after all, but Enrico doubts his sincerity.

At least one psychologist was required to attend the Order Groups on Mondays and Fridays, from 13H30 - 15H00. At work I spoke Afrikaans almost all the time, and spoke reasonably fluently as well. At an order group one Friday, Commandant Potgieter announced that the T-shirts which had been ordered several months previously, bearing the legend 'Oshakati Medics' had at last arrived.

"Unfortunately," he continued, "They are in English!"

"What's wrong with that?" I asked in Afrikaans, and the Commandant did a double take before glaring at me and then chuckling.

A beautician of some kind arrived and set up shop in Oshakati. He was a big hit with many women, who would go and have themselves `colour coded'; and be given a little booklet showing what colours they could best wear to compliment their natural complexions. These seemed to be described in terms of the seasons; women might be classified as `Spring', `Summer', `Autumn' or `Winter'. Commandant Potgieter enjoyed this situation, and stood one morning as the women filed into the staff tea room. "Morning Spring, morning Autumn, morning Summer," he greeted.

Chief Fly Spy Dirk Cloete also got in on the act. In a soft tone, he mentioned that he had swallowed his pride and taken himself off to be colour coded, and that he had been advised to wear brown for several years. I did a double take in realising that he was referring to nutria army uniforms.

Most of the dentists that I came across in the army had, at some stage in their training, made themselves a grossly distorted set of dentures to fit over their own teeth, to scare or stun people occasionally. Even Commandant Potgieter was not above wearing his on humorous occasions.

Published: 1 July 2000.

Here are shortcuts to the

Next Chapter, or back to the Grensvegter?: Table of Contents page, or the Sentinel Projects Home Page.