5 SAI Assault Pioneer (1986-87)

Martin was trained at 5 SAI as an Assault Pioneer in 1986, and served a year on the border, mainly Owamboland.

84545698 BG

"From the earliest days, we were dancing in the shadows"

-Live, The Secret Samadhi

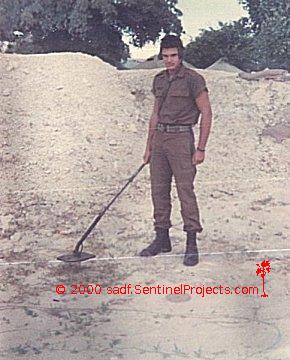

Mine Detector, Ogongo, Sector 10.

PREPARATION FOR NATIONAL SERVICE

Any preparation for what was to come was, in retrospect, futile. Nothing could prepare a relatively naieve, protected youngster for National Service in the Defence Force of South Africa. Sure, I was eager. I read everything I could lay may hands on and eagerly hung on the lips of the older, experienced chaps that crossed my path from time to time. All the GV (Grensvegter) stories I grew up on moulded my perception of what I was going to be required to do. To be honest, the concept I had was so totally romanticised that it was almost laughable. It all became brutally real in those first, few short days.

I was, at first, called to a camp, 2 SA Infantry Battalion, in Walvis Bay. This was at the other extreme of our country, on the West Coast. It would have necessitated a 3-day journey by train just to get there. It is an alien place with the great desert on the inland side and the vast Atlantic Ocean on the other. My friends laughed at me, as I was the only one called there. I sometimes wonder if they laughed because of the strange place & the great distance I would be from home, or, if they were just secretly relieved that it was not they? As fate would have it, I received a second call up instruction exactly 2 weeks before I was due to leave. I had been reallocated to Ladysmith (5 SA Infantry Battalion), considerably closer to my hometown of Salt Rock, on the Natal North Coast. I often wonder how things would have been different, had I not been reallocated...

REPORTING FOR NATIONAL SERVICE

It was a warm, sunny day when my parents loaded up my kitbag, myself and my brother & left for Durban Command. This is where we were to leave from. It is difficult to describe the emotions that I felt. I certainly was not sadness. The adventure was about to begin. There was definitely a measure of excitement and nervousness. I can remember my stomach being in a knot, all the way there. We arrived and had to park a good distance away. There were literally hundreds of cars and bodies milling about. We gathered in front of one of the big steel gates and joined the group of people. What struck me was how different all the chaps were, standing around me. Up to that moment I had been in my own peer group, right through school. Attending school functions was always in the presence of my fellow scholars & teachers. Here I was confronted, for the first time, with what was going to be my new peers. There were guys ranging in age from 18 to, what appeared 26. One could see from the body language of everyone that we all felt the same. Nervous glancing about, always one eye on the gate. We knew this was where our new lives were going to begin. Eventually the time arrived. A portly Sergeant Major with a red beret called for attention and asked everyone to say his or her goodbyes. I turned to my folks, this I remember, and kissed my mom. I shook my dads' hand and I must honestly say, I can not quite remember what words were spoken. That gate was drawing me like an irresistible magnet. Like a force, beyond my control. Little was I to know that the beast that was the SADF had struck home its first talon and had me firmly in its grip.

I think the memories of my Army days start here, in earnest ...

We were all bustled through the gate and immediately told to form groups, about 30 strong, and line up between these strange rectangular buildings, painted a drab grey. What was also immediately apparent that the businesslike, stern demeanour of the Sergeant Major had changed. He was now surrounded by a group of much younger, also red beret corporals. What struck me was that his whole manner was now like that of a caged bull terrier, waiting to be unleashed. He barked orders left and right. Oh yes, the show for the mommies & daddies in front of the gate was over. This boy was on his own turf and no one was pissing on it, no one! We were to unpack our entire kitbags in front of us. We were not to take one step away from it until one of the corporals, with a German Shepherd on a leash, had been by. I was confused and puzzled, a fellow next to me quickly stuck something into his pocket, a dog was yelping its head off at the bag of a chap in another group, the corporals swooped and there was yelling and shouting, the guys kitbag was literally pulled apart by the red berets, I stood silently, watching.

The guy next to me was now in a state. The red beret was 2 guys down and coming closer. At this stage I seem to remember the dog literally standing on its back legs, straining at its leash, trying to get to my neighbour. I needed the toilet badly. The dog let out a strangled whine and locked onto the bag next to mine, just to let go and stick his slobbering snout into the crotch of the now trembling owner of the bag. More shouting and yelling which just stirs the dog into more of frenzy. The red beret then screamed the one question that brought it all home: "Waars jou stash!!"

I was in the midst of the mother of all drug searches, no holds barred. Judging by the actions of the red berets, they were being paid to bust the dope smokers, drug users and anybody that the dogs decided had a bad attitude. I had never in my life been in contact with so much as dagga, never mind hard drugs. I was overawed. The pile of contraband grew as the search went on. By the end there was a mound of plastic bags, cans and all manner of containers piled in front of one of the trucks. It was hastily stuffed into a black garbage bag and taken away by one of the red berets. I wonder what ever happened to it all. I can honestly not say whether the guys hauled out for possession of the drugs were taken away, or joined our ranks again. At this time I was in sensory overload and my greatest anxiety was that I would not be able to repack my bag in time. Everything fitted at home but know I could not seem to fit in half of my things. I was frantic. We were told to board big brown trucks, standing end to end, in the groups we were in. I still had not managed to get my bag packed when our turn came. I gathered my bag in one arm and the few loose things left over in the other and bundled onto the truck. There, cramped in the darkness, I forced the things into the bag, breaking the zipper. There was no one to turn to, no one to ask for help, no consideration for my plight. We sat there for what felt like 2 hours. All in silence, in the darkness, taking in the musty smell of the canvas covering of the truck. I think I started realising, then, that I was in for more than I thought. It was already getting dark when the trucks started pulling off, heading for the train station.

We arrived in huge convoy. The trucks disgorging its masses of multicoloured people onto the siding next to the train. All the time there was the shouting, yelling, barking of corporals and sergeants, however, gone were the red berets, here were the green ones. A new development. These chaps seemed much more relaxed, despite the commands. They almost seemed bored. They boarded the coaches, 2 per coach, and ordered us to draw down all the blinds. Once again, puzzlement. Why do this? No one was allowed to smoke. Casual talk was only bearably tolerated. We were each handed a small plastic bag, containing a scrambled egg sandwich, and a hard-boiled egg. We were also given a small box of juice. Like this we sat for another 2 hours, maybe 3, who knows? Now one had started talking to the fellows next to, and around you. After the shock of Natal Command this was actually quite peaceful. One thing that I noticed was that many of the guys did not eat their sandwiches, they were at least a day old, or the eggs for that matter. The rougher crowd flung the eggs about as soon as the corporals were not looking. This was not my scene; I was not brought up that way. I was also not in the mood for these musty sandwiches and stuck them into a bag on the floor. My fellow passenger got my egg. Everyone drank the juices though; they were nice you see. Bags of eggshell & sandwiches started piling up in the aisles. The place started to smell. Appeals to open the window shutters were strictly denied. Boredom started to set in. The crowd started to grow restless. The corporals called the sergeants when things got rowdy. At last the train started moving and there was something to distract ones attention.

Halfway to Ladysmith a great weariness overcame me. I was not alone. Everywhere were guys dozing off on their kitbags. A quietness came over the train and I realised it was 11h00. The excitement of the day had caught up with us. It was normal bedtime for the boys. How terribly this peace would be shattered...

5 SAI AT LADYSMITH

It was about 01:30am that the train stopped at Ladysmith station. In one sentence, all HELL broke loose. There was a full contingent of the green beretted corporals, sergeants, and for the first time, officers waiting for us. There were young ones and old, hard looking men with beards and moustaches. They all seemed to have one goal, to get us from the train, onto more trucks, and away from the station. They screamed, punched, shoved and kicked us from the platforms into the street in front of the station. I saw more than one guy go down, just to be dragged by his collar, arm or leg, to the nearest truck. Guys were loosing their kitbags in the melee. I clung to mine like it was my only salvation. This was nothing like Natal Command. These guys did not, and did not try to pretend to, give a damn about us. We were cattle, going to the slaughter, why waste any compassion? Once crammed into a truck, it was time to sit in the dark again. I was shivering. I know now that it was a combination of shock & the cold. Myself, and everyone around me, was wearing short sleeved T-shirts. We had after all come from Durban, Sunshine City of Natal. It was 01:00am in Ladysmith, in the early winter; it was cold, very cold.

What happened next can simply be described as the initiation into what was to become so commonplace in the Army. The drivers of the trucks would take off at high speed, just to slam on brakes 20 meters on. Everyone unprepared would be hurled to the front of the load body of the truck. Screams of surprise and pain filled the air. I was lying on top of a heap of guys, with a few chaps on top of me. The truck took off again, causing the opposite effect, everyone was off balance and we all ended up in a heap at the back of the truck. More screaming, swearing and yelling. The truck would drive over pavements and curbs, causing us to hit the top of the frame. This was the dreaded "Roof Ride" [`roof' being Afrikaans for `recruit' or `rookie'], truly an initiation. As we filed into the 5 SAI base guys were jumping off the trucks in an attempt to get off at slow speed. They hit the tar hard; not many stayed on their feet. Once off the trucks we were ordered onto the rugby field, and told to form into loose companies of approximately 200 guys each. I later learned there were 2000 of us on that rugby field that night. Rumours started flying that there were 3 guys with broken bones from the "Roof Ride", how true this was, I will never know.

It was now bitterly cold. It was 02:00 in the morning. Frost had formed on the grass. We were marched to the "Bungalows" that were to become our home. We were tired, cold, hungry and disorientated. The bungalows were a welcome sight. Blazing electricity, warm water and, no beds, no mattresses. We were allocated 30 to a room, 2 to a cubicle. The cubicle was open to the passage leading down the middle. It was so clean it appeared sterile. A sharp whistle, a rugby referees whistle, called us all outside again. Mercifully we could leave our bags behind. We were each given 1 slice a buttered bread and a polystyrene cup of thin soup. No one threw away any bread; no one spilled 1-drop of soup.

Our group of 30 were then told to walk down to the "K.M", [Quarter Masters store], the great big warehouse sheds at 5 SAI. Once there we sat down, in group formation, behind what seemed like 20 groups in front of us. We were not allowed to lean back on our arms, we were "not at the beach anymore" according to the corporals. It was 02:30 in the morning. We sat like that till it was our turn at about 04:00. By this time all spirit and smiles had disappeared. No one said a word. We were each issued with a large steel trunk, 5 woollen blankets, a pillow and a steel folding bed, and ordered to take this lot up to the bungalows. How does one person carry all of this? Suffice it to say, for the first time we had to call on one another for help. We were not allowed to make 2 trips. Two people's things were stacked onto the beds and carried up hill, to the rooms. I can honestly say I do not know how we did it, it took forever. It was torturous work, in pitch darkness. It was so cold our hands stuck to the exposed metal. We still had nothing more to wear than what we arrived in.

We got to the bungalow at approximately 05:00am and told to now sleep. We would be called to go and draw our kit when the corporal blew his whistle again. No time was given. About half an hour later I had set up my bed, put my stuff in the "kas" and crawled under the new, scratchy blankets. The pillow smelled like old mildew. My last thought was that my first day working for Constand Viljoen & Sons was not a good one. For the first time since that morning I thought of my parents & home. In spite of being surrounded by 2000 men, I had never felt so alone.

If one had ever wondered what it must be like to be woken up by a bomb exploding in your house, come talk to me. The corporal assigned to our platoon woke us up in the old, traditional way reserved for "roofs". He placed a metal dustbin in the middle of our bungalow and detonated a Thunderflash in it. Now, this is a device made to "safely" simulate battlefield explosions such as hand grenades, anti-personnel mines and general mayhem. It looks innocent enough, but it has been used to launch the steel helmets we used, 3 stories high, over a bungalow. Detonated inside a room is akin to sucking all the air out, blinding you with light and creating instant deafness. It is a singularly Shiite experience, doubly so if it is used to wake you up. We staggered outside, all the while being sworn at for being slow. We were all still dressed in the clothes we came in, I don't think it was more than 5 degrees outside. The corporal was dressed in an "Aapjas" a thick, lined coat. It was 6:45am. We had slept for 1 hour & 15 minutes.

All of us had to "tree-aan" and were promptly marched down to the K.M again, to draw more kit. The same scenario awaited us. Row upon row of men, all sitting quietly, straight up, like meerkats. We joined the ranks and sat there for 2 hours before being issued with 2 brown overalls, 2 pairs of boots & a floppy bush hat. The corporal gave us 5 minutes to sprint back to the bungalow, stow the gear & "tree-aan" again outside the rooms. We tried our best but did not make it. The corporal was actually timing us. We took 7 minutes. The first of an untold number of punishments awaited us. For being too slow we were sent to run around a designated parking area, about 200-m away from our aantree-area. We were once again given a time limit. We ran around that parking area at least 10 times that day. We were battered & bruised, some had feet bleeding from running in sandals. A short run up behind the bungle was the mess, or kitchen. We formed up there and was each given a "varkpan", a square tray with compartments, a "pikstel", your knife/fork/spoon and a plastic cup. We looked at each other with wonder. We were going to eat for the first time since the previous night. Some of us, like myself, had only had the soup since leaving home. Inside the mess hall we were confronted with something none of us were ready for. We were served a helping of cereal, a helping of mash potatoes, a hamburger patty; mixed vegetables all topped with a helping of jelly & custard. All on one tray. The whole lot seemed totally overwhelming. We literally were given breakfast & lunch in one meal, at 10:00am in the morning. As I sat down the corporal in charge of the mess hall stood up and declared we had 5 minutes to finish our meal. We had to "swallow now & chew later". This turned out to be the format for most of our meals for the next 3 months.

Down to the K.M again, to sit in the sun and wait. The first cracks started to show. Guys were asking why we had 5 minutes to eat, all but to run down to the K.M to sit and wait for 2 hours. These was the first experience of the Army's hurry up and wait policy. It took us more than a week to come to the realisation that this is the way it was done. We sat, and waited. Waited and collected the pieces of what were to become our full military kit, all except for the rifles. When asked when we were to be given rifles the answer was always the same, "rifles are for soldiers, you are not soldiers, you are roofs". Well, the roofs were now in the middle of what we came to know as the sausage machine. What followed was an endless process of waiting, completing documents & forms, being sent back to the K.M to wait to collect another piece of equipment. All this interspersed with the 10:00am brunches, followed by 14:30pm suppers. The days started all the same, routine was beginning to set in. There was still tension between the men, seemingly encouraged by the corporals, why, who knows? Fatigue was a major factor. The early mornings, little foods, and late evenings, were taking its toll. The one thing that was a positive factor was that we were now all dressed the same. Brown overalls, boots & bush hat. All of us also had the famous no4 haircut. This uniformity seemed to create a certain type of bond between us, the likes of which we did not seem to grasp at the time. It was to be another month before I would realise what exactly was happening to our group. We were all in a world of shit, but it was the same world for all.

The day dawned when we were all marched to the 5 SAI medical bay. For us it started the same as the day before. When we arrived we were made to sit down and wait. When our turn came, somewhere about mid day we were told to file into the long passages of the sick bay. We all nervously clutched our little ARMY ID booklets, in which our names, surnames, serial number etc was written. One by one we were sat down and asked a series of medical questions. List upon list was completed. We were asked to urinate on a little strip of paper that then turned all different colours. Back into a queue to hand it to an orderly who examined it and made more notes on the, now considerable, handful of documents we carted with us. I seem to remember one of our groups chaps little strip of paper turned a very deep shade of red. He was quickly ushered away to the doctors' office, poor sod. Another fellow dropped his strip into the piss trough in the men's room. Too scared to ask for another he fished it out and handed it in as is. Heaven knows what the orderly made of that one, he passed whatever the test was anyway. Another confused bloke licked his. He also passed the test. Stout fellows we were! The time arrived for the dreaded inoculations. We were sat down between 2 orderlies and told to peel our overalls down to our waists. We were given 2 shots per shoulder. We later called it the Castle, Black Label, Hansa & Lion shots. The chap on my left took 3 tries to get the needle through my skin. He joked and said they did not have veterinary strength needles. I think they were using 3rd grade stock, if you ask me. The last test was sight. As I was already wearing glasses, I was allowed to take the test with them on. All went well, until the colour test came. I was given a booklet with 9 circles full of coloured dots. I was supposed to identify the number that was highlighted by an arrangement of dots in each circle. I was able to identify only the first 2. For the first time in 18 years I was officially declared partially colour blind. I did not know how to react. I saw that it was noted on one of the myriad forms I had with me and that was the end of it. It was never spoke of again. The impact of this colour blindness became all too real later on...

I was declared G1K1, the designation meaning I was in perfect shape for the training to come. Our group, for the first time, lost some members. All the fellows not graded as G1K1 were put into their own group. It was not 2 days later that we started seeing them in the mess hall, serving food, or in the K.M, packing boxes. The worst of the bunch were seen carrying brooms around the base, sweeping the roads. I believe there were only 3 guys that were ranked G5K5. This was the honorary grading for being sent home, medically unfit for National Service. 3 Out of 2000 men. You had to have been practically dead on your feet for this to happen. Not one single person was given a discharge for mental unfitness. There was no test for this. I know of 3 cases where such a test would have saved lives...

We were now 2 weeks down the road to becoming South Africa's finest young men. Tentatively, and progressively, we were becoming accustomed to our surroundings. The routine became comforting. It was something we could cling to, maybe a kind of security? Even the increasingly harsh treatment from the non-com officers was something one could count on. We new which ones one could talk to, or ask for help and which were only there to provide misery. We drew strength from slowly developing friendships, how foolish of us. If we only knew how short lived those would be! It was now, after we were medically graded that the actual training could start. Only one more thing remained. We had to be divided into companies of approximately 800 to 1000 men each. We were told that there would be a "Delta Company" that would have the men that were earmarked to be sent to Oudshoorn Infantry Training School in the Cape Province where the Non Coms and officers were trained. At this point all I wanted to do was be in that Company. It held all the prestige and promise I longed for. Rank held power and power had privilege. I seriously thought that if I could become an officer that I might even make the military my career. To be chosen for Delta Company the entire intake of men had to write a type of military aptitude test. We did this in the mess hall over a period of 3 days. These days are a blur as all we did was wait for our turn, interspersed with meals, inspections of our bungalows, being sent to run to the far reaches of the base and so on, and so on. All done to keep us busy, naturally. Eventually my turn came and I sat down to write the test. I prayed that I interpreted the questions correctly and tried to give my answers a bias to what I thought the Army would want to hear, and guess what? I was successful! I was elated. Under a blaring sun on the base's main rugby field the day came where we were divided into training companies and I got Delta Company!

Immediately we were put into platoons and marched away from the "rabble" down to a corner of the base. Here were row upon row of 16` x 16` tents erected that were to be our new home for the next 3 months. There was an air of expectancy and elation. There were also brand new faces amongst the non-coms. They wore recognisable insignia but in addition had the coloured whistle lanyard around their left arms. Little did we know the significance of that lanyard later on. They had "Stable Belts" beautifully coloured belts with the crossed bayonet and scabbard buckle signifying the Infantry School graduates. As a final flourish they wore the Infantry School beret badge. I was in utter awe. The officers had a detached attitude, as if we were not even a nuisance, we were not even there. Quickly the platoons were allocated tents. These were bare and had no floors, just plain grass. The tents were in a shocking state of disrepair. Some were not even complete. It was in stark contrast to the spit & shine of our previous accommodation. We knew however that this was temporary. Once allocated tents we were reformed into squads and marched to the Q.M again. What a disappointment! Once again we went through the process of having to carry beds, double bunk beds this time and heavy as hell, down to the tents. Then having to collect our kit from the bungalows and transplant ourselves to the tents. This took the rest of the day and by 16:30 we were called to form into squads for supper. Here on of the first real changes became evident. We were run up to the mess hall and we had to reform into squads after and run back in formation. No more walking for us. That first evening was a shambles. The electricity supply was not on and we only got it working at around 10pm, scurrying around in pitch darkness. We all got to bed around 12pm, exhausted. I remember a last feeling of pride before going into comatose like sleep.

We were woken up at 4:30am by shrill blasts on those whistles and screams of "tree aan" (fall in). We scurried out of bed and formed up into our squads on the strip of tar road in front of the tents. We stood there, shivering, some dresses in nothing more that their underpants, while we were allocated platoon leaders, 2 stripe Corporals that were to be our begin all and end all for the future. Our chap was Corporal van Wyk, a short, stocky fellow about 2 years older that the average recruit. He swiftly got us set aside and in a loud, but not screaming voice, ordered us back to go and dress. "Here at last we were getting somewhere", I seem to remember.

The sun was not yet up when we reformed, this time looking a little better. Corp van Wyk ran us back to the Q.M and we collected an A4 sized notebook each. Our "schooling" was about to commence.

The next few weeks are a blur in my memory. I will have to call on my friends of those times to try and recall details, however, I do know it was during this time that the most intensively physical period started. We ran, were chased, and were subjected to daily P.T sessions, never ending; gruelling, painful torture is the only description that comes to mind. Whenever we complained we were reminded that we were Delta Company and therefore had to be better, faster and smarter than the common Alpha & Bravo Companies that were the "leftovers" from selection, never mind Echo Company that were the dregs that Alpha & Bravo didn't want. This was all interspersed with hour-long academic sessions where we were taught all manner of military lore, the theory of how to be a soldier. It was during these sessions where sheer exhaustion often got the better of us and we would simply fall asleep after sitting down for more than 10 minutes. This "disinterest" was severely punished by having to sprint to real or imaginary points of reference in the base, all which obviously did nothing to remedy the situation. Tests were written after each week to see how well we listened and studied all this theory. Needless to say any outcome of the test that was not 100% was seen as failure and a personal insult to the instructor and another "opfok" (intense PT session to put it nicely, to fuck you up to but it plainly) followed.

At last the day dawned when we were unceremoniously marched to the Q.M. We did not suspect what for, nor did we really care at this stage. It all turned into great excitement when the first fellow emerged with grease encrusted R4 assault rifle clutched in his hands. We were given a gun belt and a cleaning kit. Right there on the burning concrete, sandwiched between the baking Q.M metal buildings we were officially made soldiers. Not the running around, rolling in the dust, sweating from every pore kind of soldier, the proper rifle carrying, tall and proud, capable of killing kind of soldier. It is difficult to put into words exactly what happened right there, from an emotional point of view that is. I cannot honestly say one would have seen a blatant change in manner looking at us but there was a change, immediately, however subtle. Having grown up hunting from an early age I know my feelings were not ones of trepidation or fear of the weapon itself, as was the case with some of the chaps around. Mine were more of a sense of purpose. I had a sense of knowing that these things were not my faithful old pellet gun back home or the large hunting rifle I was to inherit from Dad. This was a proper man killer, nothing more, nothing less. It was an unfriendly, hard instrument to be used for its intended purpose, and I was to wield it.

Immediately our theory classes changed to include sessions on marksmanship, rifle handling etiquette, the capacities, dimensions, operating procedures, and capabilities of our new tools. Failure to remember anything was harshly and immediately dealt with. Rifle drill was introduced to us and this we did, hour after hour, day after day, till our arms cramped up and fingers became so numb that you could not hold your fork at suppertime. The sense of seriousness and urgency became more pronounced. With these rifles our lives of little reward and frequent punishment were given new hues. Dirt & rust on the rifle, imaginary or not, were opportunities for immediate `opfoks'. Letting the thing fall or dropping it earned you an opportunity of falling next to it, without being allowed to use your hands to break your fall. The worst offence was forgetting your rifle somewhere, losing it entirely, or not having it with you at all times. The penalty for this was not anything as easy as being run till you pass out, or doing PT for 2 hours. The threat of the Detention Barracks, or D.B came into existence. The Military Police then took over and this was a fate worse than death. You were "taken away" and given a DD 1, a formal charge under military law. Time in the D.B was also added onto your service at the end, meaning you couldn't klaar uit (be discharged) with your mates after 2 years. So horrid was this threat that till today I still sometimes wake up and in that split second my first thought is where my rifle is, 14 years later. Because all these rifles were identical the only means of identifying yours was the rifle belt and the unique serial number under the barrel. This number became as much part of you as your force number and I can still remember mine to this day.

2 Months later on and we knew those firearms inside and out. They were as much part of us as our arms and legs. We ate, slept, ran, sat, went to the bog, all with them either in our hands or no more than an arms length away, all the while not having fired one live round. Talk as to when we would and how it will be was becoming the topic of conversation. Rumours started; tomorrow, next week, next month, tantalising us all the time. And then it came, one evening we were told to pack our battle jackets, ground sheets, "staaldak" (steel helmet), dixies and cups. It was here; we were going to the shooting range!

The next morning no whistle was needed to get us to "tree aan". We were ready at 4:00am, waiting for the trucks to arrive. Once again a new dimension to misery was introduced. We were formed into large platoons, dresses as we were, rifles and all, and RAN the 12 kilometres to the range. When we eventually got to the range we dropped down, totally exhausted. The Corporals had run with us, although not weighed down as we were, and they were in a foul mood for having to do so. We paid for that mood. The sun was breaking over the mountain and it was cold. You could hardly breath the thin air. We were made to sit in platoon formation and wait for the officers to arrive, which they did eventually in their truck. Our first day at the range started slowly with a platoon having to draw the targets from the store, put them up and man the "skietgat" (shooting hole behind the targets). Our platoon was lined up on the 100-meter range and allocated places to lie down. Then we were ordered to draw ammunition. At last the magical moment. Weeks of training to get to this point. We were each allocated 4 boxes of rounds, 20 to a box. When broken open the fresh 5.56mm bullets cascaded out like liquid gold. We loaded our magazines and our rifles suddenly weighed more than before, a strange feeling. This is how accustomed we had become to them. We were issued with earplugs, soft yellow sponge like cylinders that one rolled between your fingers till thin and then inserted into the ear canal where they then expanded. Quite effective, cutting out any noise as well as very efficiently blocking any commands from the Corporals in spite of how hard they screamed. This cost us dearly in the end as this very fact never seemed to convince the non comms that we could actually not hear them.

Lying down on the firing line presented its own problems. All the targets were identical and the big numbers on the embankment behind were too high to get into the same sight picture. Shooting on someone else's target lost you points, which in turn earned the wrath of the Corporal; so getting yourself lined up was critical.

Firing the R4 assault rifle is akin to a factory going to work in your hands. The trigger "creep" is atrocious, and as mentioned I was used to the finely honed hunting rifles back home. You almost have to yank the trigger as opposed to squeezing it. The whole gas blowback operation that cycles the firearm causes it to buck and move totally off target. Being only 5.56 calibre means there is not much recoil to speak of, however, it would almost go unnoticed with all else considered. Imagine 40 of these rifles firing at the exact same time. The air literally shudders around you. Blowbacks of the muzzles kick up an almighty dust cloud. The air was filled with the sharp crack of the rounds. The smell of nitro cellulose powder filled the air, mingled with oil from the rapidly heating barrels and actions. Rounds were slamming into the embankments before and behind the targets. Chunks of wood were torn from the frames that held the targets. Some rounds actually found the paper. Sharp clangs sounded where rounds actually hit the metal frames that held the wooden poles in turn. Bits of concrete were torn out of the pathway immediately before targets, singing into the blue sky. Utter, unadulterated chaos! Total, awesome exhilaration! I thought that if an enemy had to face such a barrage, even as inept and amateurish as ours, they would be cowed into submission. The absolute unpredictability of where these idiots were shooting was an ultimate danger in itself. When the last rounds ran out and we could stand back from the firing line, the silence was deafening. Mother nature herself was in check after such an event. The Corporals stepped into the breech, (excuse the pun) and let loose a barrage of their own. We would never be allowed to fire a rifle in this mans army. We were useless, incompetent, a danger to ourselves and all around us. They were going to take our rifles away, etc, etc. Very little could dampen our spirits at that point in time though. We were soldiers and we had fired our weapons.

The day wore on much in the same vein with all being berated and scorned. By that afternoon we were weary of the sun and dust and having been chased all over the 800 meter shooting range. We must have run many kilometres over and above the mornings trek. We were sat down in platoon formation and told to wait for the trucks to fetch us. We were tired and sore. So we sat for 2 hours, the sun was starting to draw low. Grumbles were heard. Corporals barked harshly. The odd person was sent on a run for transgressing somehow. Eventually by some unseen signal we were all ordered to stand up and form into sections. So started our long run back to 5 SAI base, 12 kilometres along the tar road. I could not imagine a more sadistic torture. That evening was spent cleaning our rifles that were encrusted with the carbon, dust and mud of the day. Many of us actually stripped our weapons down and showered with them, the hot water loosening the oil and carbon. The next day was to be the mother of all rifle inspections. I really don't know when we got to sleep and for how long. This much anticipated experience had turned out to be a nightmare.

Needless to say the inspection the next day turned into one unholy opfok for the whole company. I don't think one weapon was deemed to be satisfactory. In retrospect, could any have been? One reason is as good as another my good man. Now the reason became clear why such great care was taken that none of us could bring even a single live round back to the base. When pushed so far and beyond, and having the means to make it all stop with a single shot, who would not contemplate lining up the source of ones pain in your sights and ending its miserable existence? When speaking to friends afterwards it was shocking to learn how most of us were contemplating the same thing.

The concept of actually shooting another man, regardless of who he is, has lost its protection of total ludicrousness. I know in subsequent years there were incidents where troops had actually shot a training instructor. Granted, it was after the IFP, ANC, PAC cadres were incorporated into the South African National Defence Force, and lets face it, the discipline just has never been remotely the same. However, I think it came pretty close. One specific incident comes to mind. After yet another such shooting range mayhem days, one of the mortarist troops was caught balancing his trommel (footlocker) on the 3rd story fir escape landing, filled with bricks. When asked what he was doing he replied, with total honesty that he was waiting for his Corporal to come by for inspection. He was going to dump that locker on him from the 3rd story. He had enough. He would rather spend the rest of his service locked up. The lance Corporal that found him talked him off the landing and had him report sick. He spent 2 weeks at bed rest and was reclassified as G3K3 due to a nervous breakdown. He became a storeman, surrounded by trommels full of heavy stuff, stacked 2 stories high in the QM. Such was the irony of the Army.

By the way, we were warned that should any other troops try this "slapgat" (backbone-less) way out, we would not know the end of our misery. None of us did.

The days and nights rolled into one. The constant routine of running, carrying, standing to inspections, being yelled at, etc... was eroding our will to resist. One thing that contributed greatly to this ‘decay" was that we were not being fed well. I know all the stories about army food, and I will still tell a few myself, but one has to remember that we were Delta Company and not actually seen as 5 SAI troops. Our instructors were Oudshoorn instructors and themselves out of their home base. We were the last company to be fed every day, meaning we had to make do with what was left. We had to run the furthest to get to the mess hall; subsequently we had less time to eat. We were being put under much more pressure than the 5SAI troops as we were being subjected to a weeding-out program. The entire company could not go to Oudshoorn, just the best we were told. After 2 months I had gone down 3 pants sizes and 2 shirt sizes. After 3 months I had gone down a shoe size. I had never been so fit in all my life. I had never been so utterly exhausted. I had never wanted to just be home so very, very badly.

Phone calls home were allowed once a week. You stood in line to use the phones for about 2 hours. The phones were for the whole base, phone time was the same for the whole base. Calls were restricted to collect calls not longer than 5 minutes. It was well worth the wait, believe me. To hear ones parents' voices was what kept the world real. My Dad gave me encouragement to carry on. My Mom reminded me there was still someone with kind words and love out there somewhere. Throughout my Army Service I saw men cry, mostly out of despair, pain, frustration and anger, however, it was at the phone booths where I saw the most tears.

It was 2 weeks to final selection. We were being taught the finer points of parade ground drilling in preparation for Oudshoorn. We spent hours on the bleak, hard parade ground, under the unforgiving sun. If it was at all possible we turned even darker brown as the sun tanned our hides. We were chased through the obstacle course 3 times a week, almost for a full day at a time. At this stage we were tough. I'm not saying this with misplaced pride; we were truly fit and strong. Much more so than the "rest" of 5 SAI. We were treated with a bit more respect by the administration staff. We walked a bit more upright; we ran a bit faster, we kept to our own schedules. We marched better and I believe we shot better. The ragged tents we were living in were square and the sandbags were neat and full. We were "skerp" (sharp). We were all ready to get on those busses and go "home" to Oudshoorn, although none of us have ever been there for one day.

Then the night arrived that changed everything...

We were in our tents, cleaning equipment, washing, scrubbing, the normal thing. The next instant all hell broke looses. The Corporals whistles were cutting the cold night air, shouts and screams for us all to fall in, in platoons in the road. Chaos reigned, boots and kit flew and everyone was running. Once we were all formed into our platoons we were told to line up at tables that were set up inside the ablution blocks nearby. A fine misty rain had started falling and the breeze was just enough to make it chilly on the skin. Each platoon had to stand in line and each person, by alphabetical order starting with A, entered the ablution blocks, one by one. The only reason why it was being done there was that there was enough light and the instructors did not want to sit in the rain. One by one the troops emerged, grinning. "I'm going to Oudshoorn" was the unanimous verdict. And so it drew on. I did not mind standing almost at the back, my surname starting with V. Eventually the line got down to P. The chap emerged, not smiling. `I haven't been picked', he said. The first one. Very worrying, because there should not have been a reason for him not going. I knew him; he was as good as the rest of us. The second R went in, also not picked, same reason. This was the case with all the P`s. The R group, the same story. Then it dawned on me. We were told the group was too big. Although we were told to perform at our best in order to get picked, no one ever saw individual assessments or reports. No one was dismissed during the 3 months, except by own request. This group was the same size as when we started. We were never told the number that would make the grade, and why? Because they did not know, that's why. Oudshoorn draws from all the SAI camps in the country. They can only take so many. These bastards whom we trusted were told the number probably this very night and they were making their "pick" by taking the group straight off the alphabetical list.

When the full realisation of what was happening to us struck me it was almost too much to bear. It felt as if I could go up to the Major in charge and actually strangle him. The enormity of the unfairness was like a hammer to the heart, it crushed me. We were immediately separated and the Oudshoorn group was told to pack. There was elation among them. There was silence among us remaining. That night I had to move to a different tent. The next morning the busses arrived and the Oudshoorn group left. It was that quick. Our miserable bunch was told to pack our kit and sit at the tents and wait for orders. Eventually some unknown Corporal arrived and instructed us to carry our steel bunk beds to the QM stores. We were now officially homeless. We sat on a heap for the next 4 hours, not quite knowing what to do. No one was in charge. The rest of the base carried on as normal and life seemed to revolve around us. Brunch time came and we decided as a group to march ourselves up to the mess hall and see if we could have something to eat. Everything went smoothly and we blended in with the others. Afterwards we went back to our kit and simply sat there, unsure of what to do next. Quite out of the blue, a Lance Corporal came strolling up and in the most relaxed manner possible told us to move into a nearby pre-fabricated shack that was probably as old as 5 SAI itself. It was in a dreadful state, windows missing, almost no flooring, no ceiling, leaking roof. It had bunk beds and 2 working lightbulbs, that's it. This was now our home for the next 2 weeks, until someone could figure out exactly what to do with the Oudshoorn dropouts. It was during this time that I made a friend for life. This quiet, unassuming chap and I naturally drifted together. We started helping each other when heavy carrying was to be done. We shared rations and chatted when there was time for it. His name is Gert Peach and we completed the rest of our military service together. We are still friends to this very day.

2 Weeks passed with our little group being used and abused by anyone looking for casual labour. Imagine the indignity of it all. Here we were, probably the best trained recruits in the base, the fittest by far, and we have gone from hero to zero in one day. It could have been my imagination but I'm sure there were backhanded smirks when the other companies looked our way. We were seen as the failures, regardless of the fact that it was the Army that had failed us.

Eventually there came an end to First Phase. Orientation was over. Now came the time for the recruits to begin actual training in the various disciplines. We were to be divided into three main companies, Alpha, Bravo, and Oscar. Alpha and Bravo companies were already basically formed. The first phase training companies were just given their rightful names. There was a bit of swapping and adding here and there but basically they were the big "Skietpiet" (rifleman) companies. Anybody that was half alive, could see and hear, and could run was busted into Alpha & Bravo. The rest of us, and here I can say US, because we were now herded into Oscar Company, were allocated nice cosy lodgings in the modern barracks. This was wonderful, hot showers, bright light, cupboards and properly working toilets. Clean, linoleum floors, doors to our buildings.

It was soon thereafter that we were all ordered to gather on the rugby grandstand. The whole of Delta Company was there, about 260 guys in total. We were all abuzz with the reason for the gathering and soon we got to know that this was the day we were going to be divided into our respective vocations. The Corporals all formed up into a large rectangle, covering the rugby field. The Captain in charge of Delta then came forward and started asking chaps to come out and fall in behind certain Corporals on the field. Anyone with a code 10 drivers licence was to go to Corporal so-and-so. Anyone that is was a HAM Radio operator or electronics student was to go to Lance Corporal so-and so. Any person with medical knowledge or advanced first aid went straight to the sick bay Any cooks or cooking students went there, and so on. Eventually we were weeded out to the remaining 60 - odd guys on the stand. I began developing that old sick feeling on the pit of my stomach. I could see myself ending up a grasshopper (gardener) or rock painter (base maintenance) for the next year and a half. Then a Lieutenant and a Sergeant that were standing quietly one side walked up. "Who of you lot has Matric, or finished High School?" he asked. Forty of us had our hands up. "Too many" he said. Flashes of Delta Company shot through my brain. "Of you forty, who has been in hospital with nervous problems, or has parents who had nervous breakdowns?" My ears pricked up, what funny questions are these? What's going on here? There were now about 35 of us left. "Who has, or whose parents have had drinking problems? Don't lie, we will check." Now I was intrigued. We were down to 32. "Who here smokes?" About 15 hands went up. "OK, OK, that's too many. Draw straws between 10 of the smokers, 2 have to go." This is how we ended up with 30 guys, having no clue as to what we have been chosen for. "All the rest of you go with the Sergeant, you are going to be Mortarmen. The little group seemed genuinely pleased with the fact that they were going to be active Infantrymen. Once again, my doubts rose, maybe that was the good choice; we are literally the last of the bunch.

"Can you chaps handle loud noises?" the Lieutenant asked. Sure, why? "This platoon will become Assault Pioneers!" Assault what...? "... You know, sweeping roads, building roads, bridges, water purification, you know, fun stuff, boating and so on!" Brilliant, I thought, after all the blood, sweat and tears, I'm going to be a municipal worker carrying a R4 rifle, dressed in brown. I had visions of having to pack up and being bussed to Kroonstad Infantry Engineering Battalion. Great, just frigging great!

This is all that I have so far, but Martin has promised to send more!

45km Route March at Boschoek

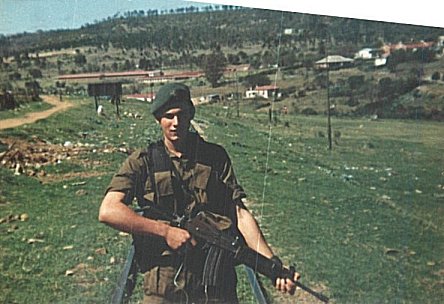

Grahamstown Finga Village

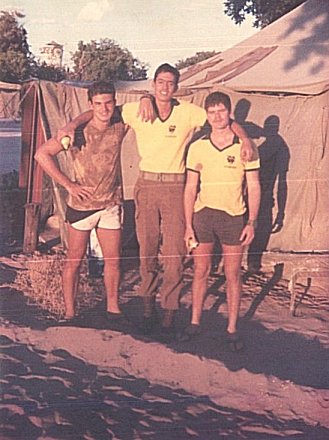

The following photos were taken at Ogongo, Sector 10. Me and 2 mates were the "Sappers" for the base for a 8 month period, it was the best 8 months of my military career.

My Two Mates

Email Martin Vorster.

Published: 26 November 2002.

Here is a shortcut back to Sentinel Projects Home Page.