911 BATTALION SWATF

BORDER DUTY 1988

By Marcus Duvenhage

(Email address:

marcduv@xtra.co.nz)INTRODUCTION

After matriculating from Fochville High School in 1981, I began my university studies at Potchefstroom University, completing my studies in 1986. The following two years I did my two years national service, commencing at Infantry School outside Oudshoorn in January 1987. The two years spent in the army would be some of the most fulfilling but also some of the most heartbreaking times of my life. From the age of sixteen all white male South African citizens received call-up instructions once a year. If you were still at school or busy with tertiary education you could apply for exemption from military duty for that year. If, on the other hand, you had completed your schooling or studies, you had no option but to report for military service usually to the station or designated assembly point nearest your home. From these assembly points the conscripts would be sent to different training units across the country. During my last year at university I received my final call-up papers. Most national servicemen were sent directly to one of eight South African Infantry Battalion camps, the so-called SAI-camps. National servicemen who had completed one or other form of tertiary education were sent, if possible, to military units that corresponded to their line of study. Engineers for example, were sent to the School of Engineers outside Kroonstad, while doctors, dentists and the like were sent the South African Medical Services training establishment outside Potchefstroom. The majority of teachers were sent to Infantry School in Oudshoorn. So it was that several of my university friends and I found ourselves reporting for duty at Infantry School's main gate on the afternoon of 12 January 1987. Little did we know what the following two years would hold in store for us.

Most of the teachers in the January 1987 Infantry School intake were placed in Bravo Company. In the beginning of the year there were more than six hundred recruits in Bravo Company. At the end of the year the number would only be about three hundred. All the recruits in Bravo Company were automatically streamed onto the officer's course, while most of the other companies at Oudshoorn were on the Non-Commissioned Officer's course. After completing the eleven-month course, members of Bravo Company would be promoted to second lieutenants while most of the other recruits in the unit received the rank of Lance Corporal.

Memories of Infantry School are mixed, some positive but mostly negative. An opinion I still hold today is that emphasis was placed on the wrong type of training for recruits at Infantry School. If the recruit was earmarked to join an SAI training camp the following year as a platoon commander or platoon sergeant the training received at Infantry School was sufficient. If on the other hand, the new Officer or NCO was slated to go to the operational area the training he received at was inadequate. At Infantry School recruits were taught how to train new recruits during their second year of national service. The new cadre of junior leaders was not properly taught nor trained how to lead their troops in an operational environment. That would only be learnt the hard way at their respective operational units the following year.

An anomaly and irritation to many troops at Infantry School was Foxtrot Company. Although not acknowledged as such for obvious reasons by camp authorities, Foxtrot Company was nothing more than a sports company. If a new recruit was good at some or other sport but especially rugby, he was immediately placed in Foxtrot Company. Here the recruits lived under better conditions and had more privileges that the rest of the troops. But for a few exceptions, hardly any member of Foxtrot Company ended up on the border in an operational unit. Most of them completed their second year of national service at one of the major Command Headquarters to play rugby or one of the other national sports.

The duration of the officer's course was eleven months. During that time about two and a half months was spent on the border. During 1987 Infantry School deployed to 51 Battalion HQ. at Ruacana. From there we did foot patrols in the area around Ogandjera about fifty kilometres south of the border. Ogandjera's main claim to fame was that it was the birthplace of SWAPO leader Sam Daniel Nujoma. After our deployment we returned to Oudshoorn to complete our Candidate Officer's course.

At the end of 1987 South African forces were embroiled in the bloody fighting in the South Eastern area of Angola. The South African troops were supporting Jonas Savimbi's forces in their struggle for survival against Cuban and Angolan forces. The now famous battles at the Lomba River and Cuito Cuanavale were fought during this time. The South African code names for these battles were Operations Hooper and Moduler. The Chief of the Army had promised the national serviceman taking part in the protracted battles that they would be home for Christmas. This seemed unlikely as the battles continued unabated, dragging on till the end of the year. A large percentage of the junior leaders taking part in these battles were national servicemen, and would be finishing their national service in the middle of December 1987. An urgent need arose to replace the outgoing junior leaders with new ones. The answer was to dispatch the 1988 junior leader cadre to the border earlier than planned. For those of us earmarked for border duty it meant we received our rank a week before the rest of our comrades did. At our passing out parade we received our "pips". This meant we were now Officers with the rank of Second Lieutenant. After a short, two-day pass, we began preparing for our final journey to the border. On the Wednesday after we had received our rank all those officers and NCO's destined for SWA climbed aboard two SAFAIR Hercules C-130-30 aircraft at Oudshoorn's airport. We had hardly left the ground when a bunch of SWATF parabat lieutenants began chanting and singing. They were going home while we were leaving home. A new and exiting adventure lay ahead of us.

After a flight of just over two hours we touched down at J.G. Strydom airport outside Windhoek. As the C-130 taxied to a halt on the apron in front of the terminal building the large rear clamshell cargo door slowly started to open. The first thing we noticed was the heat. It rushed into the cool cargo hold of the aircraft like an express train. The captain of the aircraft did not even bother to cut the C-130's engines. With the aircraft's four Allison turboprops still running, our "ballsakke" (Dufflebags) were ejected out of the aircraft on to the tarmac of the apron. With everybody out of the plane, the cargo door slowly started closing again. A minute or two later the aircraft started to roll forward to its takeoff point. The total time for the aircraft on the ground could not have been more than ten minutes. With a whining roar the Hercules rushed down the runway, lifted gracefully into the air and disappeared into the clear blue sky. All of a sudden everything was deathly quiet. Rohan De Beer, a friend from Infantry School and I stood unhappy and forlorn, feeling very, very lonely. Eventually we and several other officers who had also de-planed with us were greeted by a Commandant wearing unfamiliar rank insignia. We soon to learnt that this was the insignia of the South West African Tertiary Force (SWATF). After a pleasant introduction far removed from Infantry School's formal and bombastic ways, we were taken to Sector 40's HQ at Luipardsvlei on the outskirts of Windhoek. After being welcomed and duly processed we were taken to our allotted units where we would serve for the rest of the year. For the next thirteen months my home would be 911 Battalion, South West Africa Territory Force, situated sixty kilometres south of Windhoek at Oamites an old disused copper mine.

The Officer Commanding 911 Battalion was Commandant Gert Uys. During the following days we were made to feel at home in our new unit. The first few days were spent getting to know everybody and learning the day-to-day routine of the Battalion. Our initial welcoming phase was completed with a game of golf at the Windhoek golf club. Many of our fellow Infantry School officers were not so lucky. When they arrived at their new units they were issued with overalls, web-belt and water bottle and made to go through a gruelling physical initiation that lasted up to three weeks for some. After we had been accepted into the Battalion we were assigned our individual duties. After an interview by a board comprising the CO, Chaplain, welfare officer, Battalion second in command and the Regimental Sergeant Major, I was appointed second in command of Alpha Company. At that time of the year Alpha Company were still busy with operational duties on the border. After they had returned from the operational area their national service officers would finish their national service and return to the Republic. The rest of the Company where granted a few week's leave. After the troops return from leave we, the new 1988 officer group, would assume command and responsibility for them. In essence they would become our Company. All we were waiting for was our new company commander who was yet to arrive. In due course Captain Willem Prins, our new Company Commander arrived and we began to prepare for our first border deployment. Willem Prins was a short man with black hair and black moustache. He would turn out to be a brilliant CO, whom we all respected and learnt a great deal from. We were extremely fortunate to have him as our CO.

911 Battalion was made up of various ethnic groups in SWA. We had Hereros, Damaras, Tswanas, Basters and Coloureds in our unit. The Battalion had a reputation for being an undisciplined bunch that would not think twice before shooting one of their own officers, and in fact this had actually happened in the past. The future looked daunting. To contend with not just the enemy but also with our own troops did nothing to improve our self-confidence.

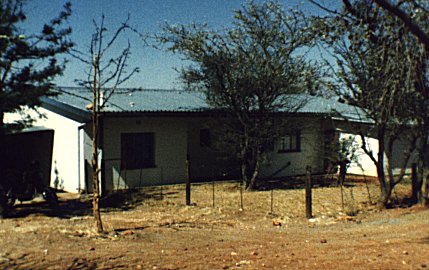

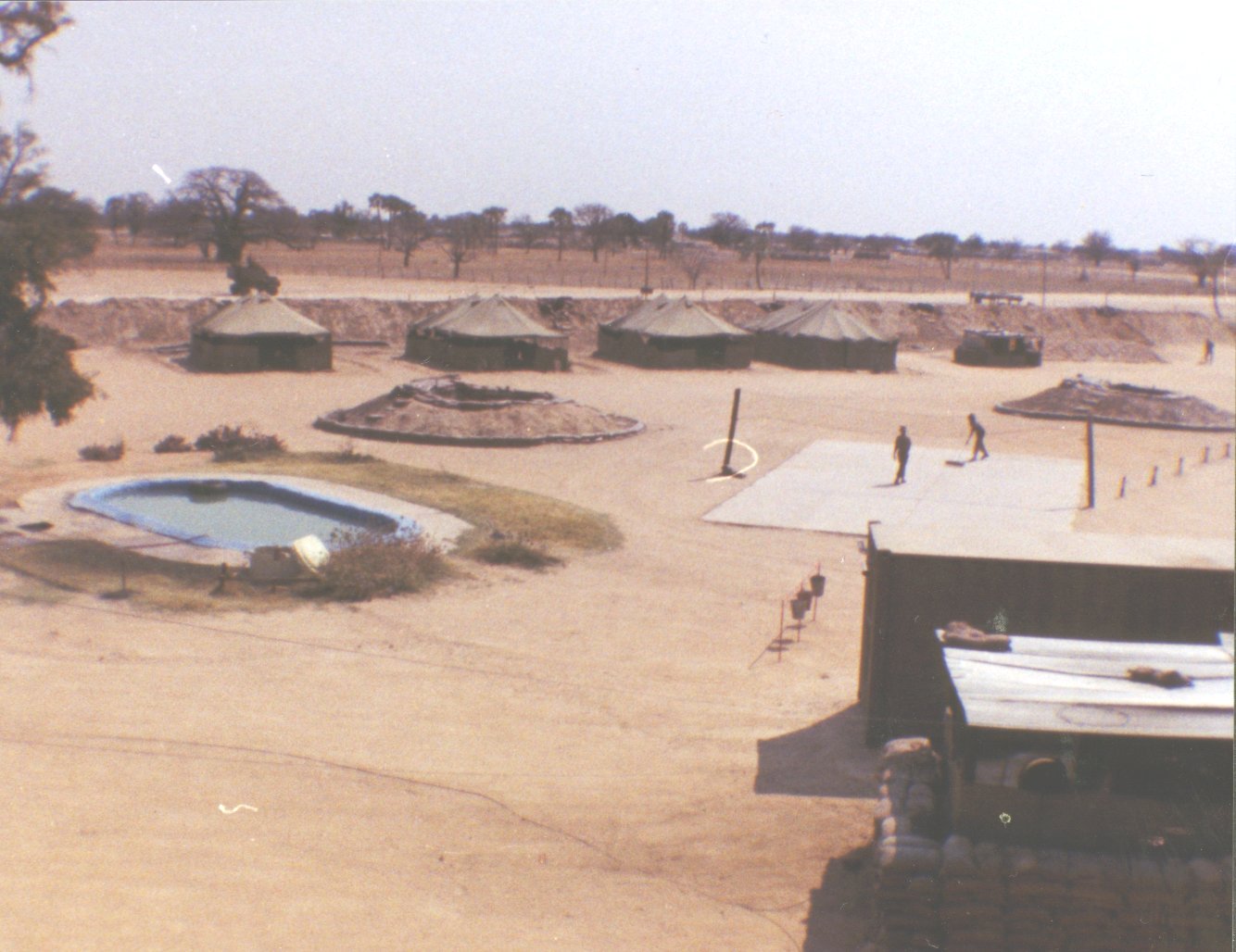

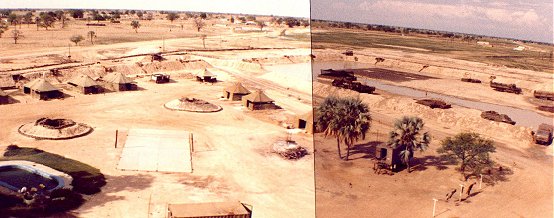

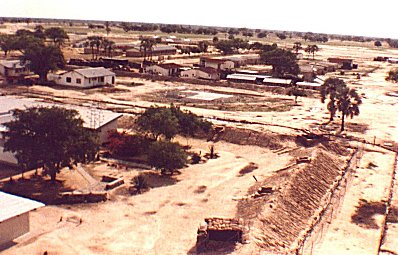

PHOTO 1 - PHOTO 4

Photos one to four depict 911 Battalion HQ. SWATF at Oamites. Photo one is a panoramic view of the HQ, general base area and the troop's sleeping quarters. In photo two and three the old mine houses the junior officers and permanent force members lived in while in the base, can be seen. There were twelve lieutenants to a house though it was unlikely to have all twelve at home simultaneously as two companies, at least, were busy with operational commitments in Ovamboland at any one time. Photo four is a view of the officers' mess a stone's throw from the sleeping quarters. The mess had a bar, snooker table, dartboard and an excellent lounge. The bar in the mess was undoubtedly the focal point of attraction for most of the officers. Many a pleasant night was spent here discussing anything from politics to philosophy.

PHOTO 5

A few weeks after our arrival at 911Bn, Alpha Company's new Commanding Officer arrived. Captain Willem Prins came to us from 2 South-African Infantry Battalion in Walvisbay. He was a 28-year old Permanent Force officer. We, the junior leaders were all national servicemen. In the coming year we would all grow to respect and admire him. He was undoubtedly the best officer I have ever had the privilege of serving under. From day one we all got on well with each other. He was strict but fair and knew how to handle his charge of national service lieutenants. We were all to learn a lot about leadership and responsibility from him during the year.

Shortly after the arrival of Captain Prins, Alpha Company's troops returned from their post border leave. Captain Barnard Alpha Company's CO up and till then, handed over command and control to Captain Prins. With the new leadership cadre in place we immediately started preparing for our first operational deployment to the border. Slowly we got to know our troops and NCO's. We began the process of re-training our troops with their new platoon commanders in charge. Pl. 1 was commanded by Candidate Officer; Willem Jobs. Pl. 2 by Candidate Officer Richard Schumacher; Pl. 3 by Lieutenant Rohan De Beer; Pl. 4 by Lt. Armand Kruger and Pl. 5 by Second Lieutenant Michael Smit. Our Company Sergeant Major was Staff Sergeant Witbooi.

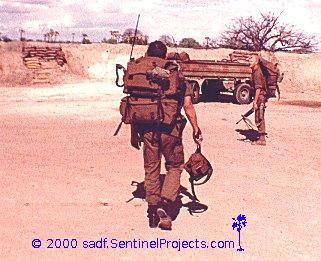

At six minutes past eleven on the morning of Thursday, 3 March, 1988 we left Oamites in a six vehicle convoy destined for Oshivello. The convoy was made up of five Samil 50 and one Kwevoêl 100. Except for one Samil that had a puncture, everything went according to plan with the trooping. At regular intervals we would stop to let the troops stretch their legs and have a smoke. It was during one of these periodic stops that the photo was taken.

PHOTO 6

SWA/Namibia is a beautiful country with many tourist attractions. One of the better-known tourist sights in the northern part of the country is the Otjikoto Lake between Tsumeb and Oshivello gate. The water in the geological formation joins up with several subterranean caves in the vicinity, all linked by underground canals. The bodies of the one or two people who have been unlucky enough to have fallen into the lake have never been found. It was strange seeing normal tourists at the sight while we were on our way to wage a war.

PHOTO 7

Photo seven depicts a typical view of the camps we usually set up at Oshivello. We arrived at Oshivello late on the afternoon of 3 March, 1988, and immediately began setting up camp, which we completed the following morning. Just as we were finishing the job at hand, personnel from Sector 10 Training Area came to inform us that we would have to move our camp, an idea we did not take kindly to! Apparently we were in the direct line of fire from the Infantry School unit doing border training at the time. We had no choice; we had to move. By Friday evening we had completed our second camp erection exercise in two days.

Oshivello was about two hundred kilometres south of the SWA/Angola border. The moment you entered Oshivello gate you were in Ovamboland. On entering the Oshivello gate you passed over the so-called `red line' which meant in effect that you were officially on the border and in the operational area. Oshivello was the joint training area for units sent to Sector 10 for operational deployment. All units either from the SADF or SWATF had to undergo a period of refresher training before they could proceed to the northern part of Ovamboland. Once allowed to deploy to the northern part of the country, units were deemed fully operational. The time spent at Oshivello varied from a few days to a few weeks. If units did not achieve a satisfactory pass rate during their evaluation they were kept behind for further re-training. Oshivello was made up of several smaller camps, the best known being Omothea where 61 Mechanized Brigade where usually stationed. During our stay at Oshivello, with Infantry School, the year before we woke one night to hear hundreds of vehicles, armoured cars and tanks move out of 61 Mech's positions. They started moving early at night and the last vehicles did not leave until dawn the next day. It seemed as if the procession would never stop. Later we found out that this was the SADF force deploying to south eastern Angola in support of UNITA during Operations Hooper and Modular.

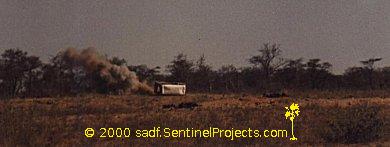

PHOTO 8

I had grown up going to a lot of airshows, lucky to have a father with a wide interest and the willingness to take me. I read all I could about aircraft and especially about the South African Air Force. According to the books, films and TV documentaries, we had one of the best Air Forces in the world. But there came a day in my life when I doubted this assumption.

During the final phase of our training at Infantry School in 1987 we did our counter insurgency (COIN) training at Oshivello/Omuthea. One day during training we were marched out to the shooting range. A firepower demonstration had been laid on by the SAAF for our benefit. There was a wreck of an old VW Combi serving as a target lying in the veld. Two Impalas were to use live ordinance in the form of rockets and 30mm. cannon against the target, followed by an Alouette III gunship which would add its 20mm cannon fire.

Now was the time to sit back and see how the pro's did it. We were expecting the wreck to go up in one great big whoosh after the first pass, as the Impalas were to initiate the attack using their 68mm. rockets. In the distance we could hear them approaching. The next moment there was a lot of dust followed by a "wruuump" like sound. When the dust cleared we were surprised to see that they had missed the target! The second pass fared no better. Was this the much-vaunted SAAF that could not even hit a stationary target? The third pass was to be with 30mm. cannons only. This also missed the target. We all started to wonder what would happen if we needed them in a real emergency. Only during the fourth pass did they manage to hit the target.

After the dust had finally settled we waited for the chopper to appear, our faith in the SAAF having just taken a tumble. Soon we heard the characteristic whine of an Allouette. Somebody in the group chirped, "Show time." He was right. It seemed as if the Allo was hanging, permanently banked over the target. Above the whine of the turbine the distinctive thud, thud, thud.... of its 20mm. cannon could be heard. With every few thuds the Combi would disappear under a cloud of dust. It was soon shot to pieces. With the help of the Allouette and its 20mm. cannon the SAAF had redeemed itself. Our confidence, momentarily lost, was soon restored. During the following year I was to witness on more than one occasion the true ability of the men and machines we saw that day.

PHOTO 9

During our period of retraining we gave a lot attention to three major battle drills, i.e. patrols, vehicle movement and night ambushes. In photo nine we see Lt. Armand Kruger the platoon commander of platoon 4 and his platoon sergeant, sergeant Mabarukua. The photo was taken during one of their vehicle movement evaluation exercises at Oshivello. Alpha Company was in the lucky position of having a large percentage of full lieutenants. Rohan, Armand and I had all completed tertiary studies before commencing our national service. We were a few years older than Willem Jobs, and Michael Smit who were second lieutenants. Richard Schumacher was a diesel mechanic but as he did not have a university degree or diploma, at that time, he still had the rank of Candidate Officer. Later in the year both he and Willem Jobs would be promoted to the rank of Second Lieutenant. There was an advantage to having somewhat older and more mature officers in the company. All the officers got on very well with each other during the year. We did our work enthusiastically, thoroughly and with pride. We were undoubtedly the most successful company in the Battalion during 1988. This success ranged from the best training and operational results to winning the battalion's rugby trophy for the year. This success was due in no small part to the dynamic leadership of our company CO.

It was during our first stay at Oshivello for the year that something very interesting happened. One night, just after supper, Sergeant Mubarukua approached me and requested to see me privately. I agreed, and we walked a short distance away from the rest of the troops. The sergeant informed me that he and the rest of the platoon had a problem with their new lieutenant. I was both shocked and surprised to hear this. He continued by telling me that Armand did not want to be part of the platoon. According to the sergeant, everybody in the camp, including Captain Prins and myself ate directly out of our dixies, dirtying them in the process. Armand did not do this. Before he ate, he would pull a Jiffy plastic bag over his dixie. He would then place his food on the plastic inside the dixie. After he had finished eating he would pull the plastic bag off the dixie and throw it away, keeping his dixie clean in the process. This was unacceptable to the troops. They wanted him to get his dixie dirty just like the rest of us. I respected the sergeant's wish and asked Armand, in future, to eat directly out of his dixie. I learnt a lesson that night. Nothing is too small to be unimportant.

The incident mentioned above was not the only one Armand was involved in during our stay at Oshivello. As part of the retraining program all the platoons had a host of tasks to complete. One of the most important battle drills to be practised was the setting up and initiation of night ambushes. The initiation of a night ambush is a very spectacular affair. There are lots of mortar bombs exploding, flares bursting into brilliant light, mines detonating and, LMG and R.4 tracer fire criss-crossing the night sky. Being part of such an ambush definitely gets the adrenaline flowing. If done correctly it is an experience to behold, but if performed incorrectly it can be very dangerous for all those taking part. We had set rules and procedures known as Standard Operating Procedures (SOP's) for the laying and initiating of an ambush. The following incident happened during Armand and his platoons last, live training ambush before their scheduled evaluation a day later.

Armand and his platoon had moved out of our base during last light and proceeded to their predetermined ambush position. Once at the position Armand and his platoon sergeant went about preparing the ambush position. This entailed the setting up of the Claymore mines to cover the ground where the enemy would supposedly be walking. This area was commonly known as the `killing ground' or `death's acre'. The two leaders had further duties, such as the sighting and placing of the 60 mm patrol mortar, the positioning of trip-flares and lastly the laying out of the arcs of fire for the LMG's and riflemen with their R.4 rifles. During training it was important to place the deadly Claymore mines at least thirty meters away from the positions of your own troops as the nasty little mines had a back-blast that could kill a person who was near enough.

After Armand and Sergeant Mabarukua had completed their preparations, they entered the predetermined ambush position. They would stay in these positions until the ambush was initiated. Just after 21:00 hours we received a radio message from Armand informing us that we could come out to the position to witness the initiation of the ambush. Apart from experiencing the thrill of the ambush, it was also my personal task as safety officer to ensure that everything was safe at the ambush site and that all the prescribed drills and regulations had been adhered to. After arriving at Armand's position I climbed out of the Buffel Armoured Personnel Carrier, and walked over to where Armand and his squad were lying, being careful not to step on any of the wires for the Claymore mines. As I knelt next to Armand to confirm that everything was safe, he told me that the Claymores were not the regulation 30 meters away, but a little nearer, due to trees in the vicinity. He assured me though, that he had placed them in such a way that when the mines detonated their back-blast would be directed back into the ground, and the lethal fan of steel balls would explode forward and upwards. I had to make a decision, should we continue or should we disengage? I decided to go with the ambush but told the troops to keep their heads well down until the Claymores had detonated. We would all be safe as long as everybody stayed well down until after the mines had detonated. I told Armand that he must wait for me to lie down next to him before he detonated the Claymores. After doing my final checks along the line of waiting troops, I started to kneel next to Armand intending to lie down next to him, when there was a blinding flash accompanied by a very loud explosion. The air was punched from my lungs as I dropped the last few centimetres to the ground. During the next few minutes all hell was let loose, as the trip-flares were ignited and the 60mm. mortar began to fire illumination and high explosive rounds. The troops were shooting with mixed ball and tracer ammunition and the LMG gunners were really enjoying themselves. It was a sight that would make any man's adrenaline rush. For just two short minutes the fury continued unabated, and then stopped, as abruptly as it had begun. While all this was going on, I had got my breath back and started looking for Armand. He had initiated the ambush without waiting for me to lie down.

PHOTO 10

An infantryman is not known as a foot soldier for nothing, he marches where he wants to go. In this early morning photo of Platoon 4 the troops have just started on their way back to camp after rounding the Buffel that was the turning point for their route march. The total distance for this training route march was 16 kilometres. It might not seem far but the troops were in full kit and the terrain underfoot was very sandy which made the going difficult and tiresome. Most of our troops were relatively fit. They were all volunteers and were known as Fighting Support Service troops. Several of the troops had been in the Army for more than ten years and were well versed in the ways of soldiering. During their time in the army they had learnt their respective positions and roles within the company in general, and their platoons in particular. For example, rifleman number one knew exactly what to do in the event of a mine incident. He ought to have known seeing that he had been doing the same job for ten years. The average age of the troops was nearer 26 than 19 as in the case of the SADF. Our troops were experienced soldiers with a lot of operational time to their credit. The advantage of this was that they always achieved above average marks, usually in the 80 percent range during their evaluation periods at Oshivello. It was not uncommon to have a unit sent back to its home base for further training after failing to make the grade at Oshivello. Luckily this disgrace did not befall us with our three visits to the training area during the year.

PHOTO 11

In this scene two members of Alpha Company are busy with platoon weapon training. The weapon they are training with is a 60mm. patrol mortar also known as a Patmor. The bomb they are about to drop into the mortar is a 60mm. smoke round. The Patmor was originally developed by the Israelis in the late 50's. It differed from the standard 60mm. mortar in not having the normal heavy base-plate and tresses, nor a standard sighting device. The Patmor was designed as a light man-portable weapon so it could be carried on patrol by infantrymen. The weapon was very simple to operate. One simply took hold of the mortar by its handle, jammed it down on the ground, aimed and elevated it in the required direction, armed the bomb and let it slide down the tube. The range of the Patmor is about 1 100 meters with full charge and can fire several different types of bombs; i.e: high explosive (HE), smoke, illumination, and training rounds. The illumination bombs were set to go off seven and a half seconds after being fired. The morning after a heavy night's shooting, the veld and trees would be covered with small white parachutes from which the burning illumination pods had hung. The colour of an illumination bomb is not white as is commonly believed, but more a copper/brown colour. As the illumination round drifted to earth it would make eerie shadows on the ground as the light from the flares danced between the branches of the trees.

The troops became quite adept with the Patmor. It was not uncommon to see them hit a target at more than four hundred meters after only one or two practice shots. During one of our training ambushes an amusing incident occurred. Some new troops were giving support and illumination fire with the Patmor when all mortar firing suddenly ceased. With the mortar not firing illumination rounds the troops could not see what was going on. In the sudden darkness, I ran over to the mortar emplacement to find out what the problem was. The troops informed me that the weapon would not fire. As they were inexperienced with the weapon, they did not complete the immediate action drills required by the training manual. The problem was quickly found. A strand of elephant grass had got caught between the bomb and the inside of the mortar pipe. The grass had effectively wedged the bomb in the mortar. I simply turned the mortar up side down and let the bomb drop into my hand. The troops did not like this as they believed it might still go off. Luckily it could not, as the bomb first had to be fired before it could arm itself.

I can not vouch for the following incident as I did not personally experience it, but rather heard of it along the grapevine. Apparently some troops were busy one day, erecting tents at a border base when one of their number needed a hammer for the tent anchors. He could not find one quickly enough so he took the second best thing that was lying nearby, a 60mm-mortar bomb. Unfortunately for him it was of the high explosive (HE) variety and it did not take kindly to being used as a hammer!!!

PHOTO 12

PHOTO 13

The time the company stayed at Oshivello varied from three days to two weeks. At 12:30 in the afternoon of Friday 11 March 1988 we departed from Oshivello in three Samil 100's for Ombalantu. The journey to Ombalantu was not without incident. On the way, one of the Samils hit a horse and injured it so badly that it had to be shot. Another Samils rode over a donkey that ran across the road and to crown it all, one of the troops had his foot run over and broken by yet another Samil, and had to be left at Ondangua sickbay. We arrived at Ombalantu just after four o' clock the afternoon. Just as we were driving into the base, we were greeted by the whine of two Allouette III helicopters landing on the base's chopper-pad. Minutes before our arrival they had been supporting Koevoet with a contact seven kilometres north of Ombalantu. We soon realised that life on the border was going to be somewhat different from what we had been taught at Infantry School. `Sideshows' were out. Here we would have to think and act on our feet. A wrong decision could mean the difference between life and death for one's troops and for oneself.

Ombalantu was situated next to the main and only tarred road in northern SWA, roughly half way between Oshakati and Ruacana. Oshakati was the HQ of Sector 10 and Ruacana the HQ of 51 Battalion. Ombalantu was a company sized support base with a normal contingent of between a 150 and 200 troops. Ombalantu's single greatest claim to fame was a huge Baobab tree in the base. Inside the trunk of the grand old tree was a small chapel with a stone pulpit and stone seating for about twenty troops. It was never used for its intended purpose while we were in residence there. What it did present to a lot of us was a place of solitude where one could experience some peace and quiet. It was always quiet and cool inside the tree, an ideal location to escape the scorching Ovamboland heat. Another well-known tree on the border was the one in the Caprivi strip that had a toilet in it. Our tree had the advantage of being bigger and a place of worship to boot!

The building with the yellow roof was our "coffee bar". Inside there was a video, TV and some Christian reading matter. The vehicles just visible in photo 12, belonged to 32 Battalion. For a number of weeks we had a troop of 127mm. Valkery rocket launchers stationed in Ombalantu. They were to lend fire support to our base in the event of an enemy attack from Angola. At that time the Cuban 50 Brigade was just across the border from Ombalantu. There was the very real possibility that a joint Cuban/MPLA force might invade SWA and overrun our base. If they did this we would not have been able to stop them with our two puny 81mm mortars, the biggest support weapons we possessed at the time. The range of the 81 mm. mortars was insufficient to counter SWAPO's 82 mm mortars, 122mm. Katyusha rockets or, for that matter, most of its artillery.

PHOTO 15

The creation of a unit and sub-unit identity is very important in the military culture. The creation of an identity helps to foster a feeling of pride and unity amongst the members of a Battalion and Company. It builds the esprit de corps of the troops involved. One of the ways of forging a strong bond between individual troops and their unit is by way of unit badges and emblems. Each 911 Bn. Company that served at Ombalantu had its own badge or emblem on permanent display next to the operations room. Alpha, Bravo, Charlie and Delta Companies emblems are visible in the photo.

Contrary to what most outsiders think, military bases on the border were at all times clean, neat and tidy. Under the ever-watchful eye of Staff Sergeant Witbooi, the troops kept Ombalantu in a good state of repair. The sand in the base was swept and raked every day. Neat patterns were made in the sand, in our so-called garden, where the emblems were kept. The troops took great pride in the upkeep of their base. It is understandable they felt this way as they spent a large part of their working lives in it. The feeling of loyalty the troops felt for their border home is clearly highlighted in the following incident.

Near the end of our final border stint a new doctor was posted to Ombalantu. During his first night in the base all the officers and our new doctor were having a drink in the officers mess. Feeling the need to shake the dew from the lilly he stepped outside for a moment to answer the call of nature. This he proceeded to do against the wall of the officers' mess. He had hardly rejoined us when one of my troops asked if he could see me. He requested me to inform the doctor that relieving himself in public in full view of the troops against the outside wall of the mess, was not to be done. There was a toilet for that type of thing. I fully agreed with the troop and informed the doctor accordingly.

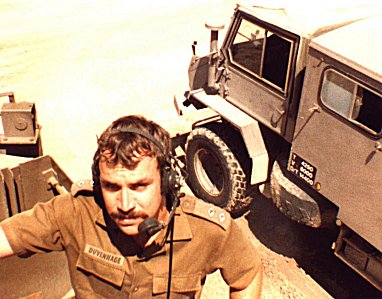

PHOTO 16

Corporal Liebenberg, more commonly known as "Lieb", was the only white NCO in the company. He was our transport NCO but was more a jack of all trades. He was older than the national service officers and was one of the few of us already married. How he came to be at 911 Bn., we never could find out. Apparently at some or other time he had struck a senior officer. This led to him being demoted and posted to the outback of the military world. In the photo Lieb is sitting on the "bin" at the back of a Buffel mine resistant vehicle and he is holding the handset of an A-53 VHF radio.

PHOTO 17

PHOTO 18

PHOTO 19

These three photos were taken about 50 meters south of the border with Angola in the vicinity of Beacon 10. In photo16, Lt. Armand Kruger with the cigarette is talking to two Forward Observation Officers from 32 Battalion whose battery of 127mm Valkery MRL's was stationed in Ombalantu. The officers had their observation post about ten kilometres from the base in the general area where it was expected the enemy would place their heavy weapons if they were to attack Ombalantu. If the enemy had attacked the FOO's would have brought down counter fire onto the enemy's positions, from the MRL's back in the base.

Every ten kilometres along the border there was a cement beacon. These beacons were about a meter high and a meter square at the base tapering to a squared off top. On the one side was inscribed "SWA" and on the other "Angola". We used these beacons as handy navigation way-points. As can be seen in the accompanying photos the terrain in the vicinity of the cutline was mostly flat and featureless. It was very easy to cross the border without realising it.

PHOTO 20

The photo was taken from the observation tower or "OP" situated on top of Ombalantu's operations room. The buildings in the foreground housed the two generators a 35 and a 100 KvA which the base needed for its electricity needs. The swimming pool was for the use of the troops as was the cement slab, where they played volleyball. No border base was complete without its volleyball-court. The tents in the background were the sleeping quarters of the troops. One platoon was kept in the base on a rotational basis, while the other four platoons were out on patrol. The platoon doing duty in the base had to look after the day-to-day running of the base as well as providing protection for it.

The two oval-shaped dugouts in the middle of the photo were the emplacements for the base's two 81mm. mortars. These two mortars were the only "heavy" weaponry permanently in the base. Their task was to lay down a counter bombardment in the event of an enemy attack on the base, a task they accomplished more than once during the year. The mortars were generally in a poor state of repair. Countless requests to 51 Bn HQ for new weapons fell on deaf ears. It always seemed incomprehensible to us that an operational border base was unable to get decent, serviceable equipment. The 81mm. mortar had a range of about five kilometres when firing HE bombs and three kilometres when shooting illumination rounds. We were to find out that this range was insufficient to counter SWAPO's 82mm. mortars or his 122mm Grad-P rockets, that had a range in excess of ten kilometres.

PHOTO 21

In this view looking east the vehicle park and chopper pad are discernible. The Ratel IFV at the right of the photo belonged to a troop of artillery men seconded to Ombalantu. They were equipped with three 120mm mortars. Where as the 81mm mortar was still seen as an infantry support weapon, the 120mm variety fell under the control of the Artillery Regiment. The chopper pad with its tarred landing zone was protected from small arms fire and shrapnel by the earth embankment surrounding it.

PHOTO 22

These are the remains of Russian made 122mm. rockets fired from a Grad-P launcher, after a SWAPO stand-off bombardment on Ombalantu. These 122mm rockets were well known to a lot of South Africans who took part in Operation Savannah in Angola in 1975-1976. During Savannah they received the nickname of "Red-eye". The name was due to the fact that it was possible to follow the trajectory of the missile from its launch till it exploded on impact with the ground. It was possible to follow it due to its bright burning exhaust signature. The Red-eye was more commonly known as the Stalin Organ especially when fired in salvos from Ural trucks. The rockets in the photo were fired from a single tube Grad-P launcher. The launcher and a number of missiles were usually brought across the border from Angola at night, most often on bicycles. SWAPO would set them up two or three kilometres south of the border and fire off a salvo at South African military targets that were in range. These targets were mostly permanent military bases. After they had completed "revving" their intended target they would scamper back across the border before any follow-up action could be initiated by the security forces. At this stage of the war late in 1988, SADF and SWATF forces were prohibited from crossing the border in pursuit of SWAPO elements. The same could not be said for SWAPO though, who violated the border as and when they pleased knowing full well that a blind eye would be turned to their actions by the UN and the rest of the world.

The 122mm rocket was known as an `area denial' weapon. The weapon's high explosive warhead was encased in thousands of small steel balls that spread out in a lethal killing field after the rocket had exploded on or near its intended target. The weapon was not very accurate but it did not need to be as its intended use was against large troop concentrations. After one attack on Ombalantu our walk-in fridge was so peppered with shrapnel that it looked like a colander. The Grad-P had a longer range than our 81mm mortars while our 120mm mortars could just about match its range. To counter any further Grad-P attacks or any other attacks for that matter on the base, Ombalantu received a troop of four Armscor built Valkerie 127mm MRL. South Africa's version of the Stalin Organ.

PHOTO 23

During SWAPO's first bombardment of Ombalantu during Alpha Company's stay, they used two 82mm. mortars. They were positioned a little over 1 700 meters from the base. Their base-plate positions could be roughly judged by looking for the flash from their mortars every time they fired and counting the seconds till the bang was heard. With the `flash to bang' principle, it was possible to judge the distance. Once the enemy's positions had been ascertained, it was possible to lay down counter fire with the base's 81mm mortars and the LMG's in the guard bunkers. The morning after the first attack, the little goat in the photo was found near the site of one of SWAPO's mortar positions. It was lying next to its mother who had been killed in the crossfire. It was still so young that its umbilical cord had not yet fallen off. Like most troops the world over, our troops immediately adopted the little goat. They brought it back to base where they started to hand-rear it. However, its future did not bode well. The troops took it back to Oamites with them after our first border stint was completed, but unfortunately it died soon after one very cold night, due to exposure.

PHOTO 24a

For a large part of 1988 I was seconded to 51 Battalion at Ruacana. My job at 51Bn HQ was that of SO.3 Ops. In other words I was the battalion operations officer. 51 Bn. had no permanent troops of its own but rather drew company sized detachments from normal SADF and SWATF infantry units as and when needed. During 1988 some of the better known units to do duty at 51 Battalion were companies from of 201 Bn. The Bushmen from Omega, 701 Bn. from the Caprivi, 2 SAI from Walvis Bay and 911Bn. and 32 Bn. as well as small elements from 5 Reconnaissance Commando from Phalaborwa. During my tour of duty at Ruacana, I stayed in the lines belonging to a troop of armour men and their Eland 90 armoured cars (`Noddy cars'). Our sleeping quarters were situated about 50 metres from 51 Battalions underground operations room. While walking with fellow officers from my home unit, we heard a distant rumble. We all recognised this as the sound of powerful jet aircraft. It was not the whine of a helicopter, as the sound of an Allouette or Puma is very distinctive. The rumble had a much deeper tone to it. I mentioned to my companions that it was strange for our Mirages to be flying about in our sector of operations as we seldom heard and much less saw them. We were used to seeing and hearing our Impalas. If the Mirages were flying so far north it usually meant that a major contact or battle was underway.

All of a sudden two sleek jet aircraft flew over our base at a very low altitude. I immediately recognised the type and origin of the aircraft, and urged my friends in no uncertain terms to get moving. We set off like scalded cats for the relative safety of the ops. room. At least it offered a measure of protection against shrapnel.

Situated around the base at strategic positions where three anti aircraft towers. The crews manning these towers came from a South African Cape Corps Anti-Aircraft troop. Just as we ran into the ops. room we were in time to hear them reporting by radio to the ops. officer on duty that: "Twee van ons Imp. mechies het nou net hier oor gevlieg!" (`Two of our impalas have just flown over!')

The planes that had passed overhead were not SAAF Impalas but Angolan MiG 23's. The Cuban pilots had kept radio silence all the way from their base, probably Lubango, and flew under our radar cover. We later found out that they had done a photo-reconnaissance of Ruacana. I still wonder today what the AA troops, who are supposed to know these things, would have reported if a 747 had flown over.

During later duty I stayed in the lines of a company from SWA-Special forces. Their speciality was tracking, hence the emblem in front of their tents. Apart from their tracking prowess they were also exponents of the 500-CC. motorcycle scrambler.

Photo 24b

Ruacana, being the HQ of 51 Bn. had a permanent MAOT (Mobile Air Operations Team) on the base. There were two Allouette III's permanently stationed at Ruacana and a Bosbok fixed-wing aircraft at Hurricane Base three kilometres away. The choppers were on continuous standby for any emergency, from a bee-sting to a contact with the enemy. The CO of the MAOT usually held the rank of Major. One of the most pleasant officers I had the privilege to meet on the border was Major Chisolm. He came from 15 Squadron at Durban and was on detached duty as CO of the MAOT at Ruacana. From time to time the "blues" would take on of us "browns or pongos" on a so-called "Bakkie ops." as in light delivery van operation. These flights were flown with the Bosbok stationed at the landing strip at Hurricane, an infantry base about three kilometres from Ruacana.

One day I heard my name being called on the base public address system. I was to report to the MAOT tent immediately. Talk about greased lightning! They had hardly finished calling me when I charged into their ops. tent. After receiving a R.5 rifle and a few clips of ammunition, I was introduced to the pilot. I cannot recall his first name but he was nicknamed "B.C", short for Beresford-Carter, his surname.

The aim of the flight was to look for any suspicious vehicles or civilians across the border in Angola. If we saw any, we were at liberty to have a go at them with the R.5 rifle I was holding. The aircraft itself was not armed. After flying for a while, B.C. asked me if I wanted to fly the plane. First he showed me what the little pointed hat on the control column did if you moved it up or down. Later I was to find out this was the aircraft's trimming device. Remembering what I had read in books, I did not grab hold and choke the control column. I held it gently and tried to focus on something on the horizon, trying to fly straight and level. After a few moments I felt the aircraft pitch down. "You are climbing" was all I heard from the front. After this happened a few times I made a mental point to concentrate more closely on the altimeter. We never flew higher than 50 metres above the ground during the whole sortie.

After taking off we flew east, parallel to the cutline for a number of kilometres, then turned north until we were over Caloueque. From there we proceeded south west until we reached the Ruacana dam and waterfall. B.C. told me to fly low over the dam. I tried to do it but it seemed as if we were about to hit the water. He then took over and showed me what he meant by low over the water. The Bosboks wheels were centimetres away from the surface of the water. After a few passes over the dam we returned to Hurricane. As we were nearing the base, we spotted two Allouette III's on their way to Ruacana. The two Allo's diverted and landed at the airstrip from which we had taken off, from were we hitched a ride back to Ruacana with them.

We did not see any Cubans, FAPLA or SWAPO. It did not matter. I had just enjoyed the flip of a lifetime and the best of all, I did not have to pay; that is if you don't count the two years of my life spent in the service of Botha, Malan and Co. This was not the only bit of pleasure the SAAF provided me during my time on the border. The following incident is worth mentioning if only for its visual impact it had on me and those few who were lucky enough to see it with me.

While travelling in a Buffel between Ruacana and Ombalantu, a distance of about eighty-six kilometres, and had a short, sharp, encounter with a Hercules C-130 of the SAAF. I was standing in the right-hand side of the Buffel when in the distance, I saw a large aircraft approaching. As it got closer I recognized it as a SAAF C-130. It could not have been higher than 30 metres, or so it seemed, above the tarred road charging headlong towards us. I frantically grabbed my A-53 radio and started to change the frequency to 47 000 Mhz., which was one of the air to ground frequencies we used. All this fumbling took time and by the time I was ready to speak the Hercules had rushed overhead. I still tried to call him up but I doubt if he ever heard me. The sight and sound of that huge aircraft thundering overhead, just a few feet above the ground will stay in my memory for a very long time. It was a most magnificent sight to behold.

The Airforce and Army's different working procedures were brought into perspective by comparing the SAAF's to the Army's way of doing things. The SAAF had a more laid back approach to a lot of things, but one always got the impression that they knew what they were up to and did their work very professionally. The permanent force members of the Army, especially the senior officers were for the most part bombastic and in some cases totally incompetent to do the work at hand. Some officers were the archtipical "Colonel Blimp" types. One got the distinct impression that some of them had an inferiority complex and could only function by keeping subordinates in constant fear and trepidation.

It was while serving at Ruacana that the long held belief I had about the invincibility of the South African Army disappeared very quickly. For as long as I can remember the idea was fostered in the youth of South Africa that the SA defense force was well nigh invincible. An idea given impetus by the old National Party's propaganda machine. On more than one occasion I was to see senior officers not being able to master a difficult situation. When things started to get difficult these officers would start shouting and screaming at the people around them. It was not uncommon to see an officer of junior rank take over and bring some semblance of order to a potential life-threatening situation. After the crisis had passed it would be the same officer who could not handle the pressure who would make derogatory remarks, swear at and chase subordinates out of his office for no greater reason than their not answering quickly enough when shouted at. Luckily not all the officers were like the ones just mentioned. Most were competent, hardworking and trustworthy. In a difficult situation the following holds true: When the going gets tough the tough stay calm and start making decisions. (The tough are not supposed to crack-up and go to pieces.)

The most important characteristic that marks a young man's journey from youth to adulthood is his ability to comprehend and accept responsibility. He must learn how to be take responsibility for his actions and must be able to make the right decision when this is called for. The decisions that a lot of young soldiers had to make on the border were at times awesome. It was not uncommon to see a nineteen-year-old second lieutenant take control of 200 men and millions of rands worth of equipment. A wrong decision by him could lead to the death of any number of his troops and the loss of irreplaceable military hardware. The burden of responsibility lay heavy on such an officer. How ironic it was that this same officer was not allowed to see a 2 to 21 movie back in the Republic due to the amount of violence depicted in it. Some of these young men saw more real life violence in a day than Hollywood could dish-up in a year!

The responsibility that a lot of officers shouldered is illustrated in the following incident. During the final stages of the war, Armand Kruger and his platoon were working in the vicinity of Beacon 10. At that time a joint Cuban/FAPLA/SWAPO attack on SWA was a distinct possibility. During my regular visits to the platoons deployed in the field Armand Kruger informed me that he could hear the enemy's vehicles moving about, barely three kilometres north from his position just across the border. All that Armand and his men had to protect themselves with in case of a full-scale attack was one 60mm Patmor with twelve bombs a RPG - 7 rocket launcher with six projectiles and their personal R.4 weapons. The Cubans on the other hand had tanks, armoured personnel carriers and artillery. If need be they could call on air-support from the newly constructed airbase at Xangongo barely sixty kilometres from the border. After dinner one evening, Captain Prins and the rest of the officers retired to the observation post above the ops. room. Here we would watch the sun go down and while away the hot day with pleasant conversation. While discussing the following day's tasks Captain Prins remarked that if Armand was to be attacked at his position, he would not hesitate to send in the whole SA Army to go and save him. He continued talking, remarking he could not bear the thought of talking to Armand's fiancé if he were killed, seeing that it was he who had given Armand his patrol orders. At that moment I realised how demanding it was to take responsibility of other people's lives and how difficult it can be at times to be a worthy leader of men. The old adage of "The loneliness of command" rang true on that cool evening. The lesson in human understanding and responsibility I learnt that night is something I shall never forget.

No decision is more difficult to make than the one relating to another human being's life. But these types of decisions had to be made and we made them daily. We had to take command and we had to lead our troops, there was no choice, it had to be done. It was a time of being young and feeling vibrant and confident. We learnt to do things quickly, correctly and with confidence. We learnt about ourselves and we learnt about each other and we learnt about trust and honesty. Above all we realised that we were capable of much more in life than we had at first thought possible. It was in these circumstances that one could become addicted to adrenaline. I am of the opinion that is why a large number of troops could not at first adjust to normal civilian life after completing their national service, especially those that came from the border. It usually took a week or two to get accustomed to civilian life again. Here I might add that I do not believe in the "Bossies" syndrome. A lot of national servicemen returning from the border would claim PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) when all they were looking for was some attention back home. A lot of so-called PTSD cases were never near the operational area but would claim to be Rambo's when back in the Republic. This is the despicable type of person that even today proclaims to all who want to hear, how brave they were and how many terrs they killed. They usually become very vociferous after a few drinks when they have enough Dutch courage to talk the rubbish their IQ's permit them. I, like the majority of us who were on the border, have nothing but loathing and contempt for these so called "bush fighters".

That certain soldiers suffered from PTSD can not be denied but that it was endemic was not the case. It is interesting to note that there was no psychological support from the side of the Army for soldiers once they had completed their border duty or national service. If there was such a support service, I for one was not aware of it. Once a national serviceman had completed his compulsory duty to his country, the Army conveniently forgot about him. That is until he was needed to do one of his periodic camps. Most of the returning soldiers did not talk much about the war on the border. Mainly because they believed the people at home would not understand if they did. This inability to communicate one's emotions played a large role in a lot of ex-servicemen's social adjustment problems after their return home.

Photo 25 - Photo26

These two combined photos show a view looking north from the base. The dark ridge on the horizon is in the general area of the border with Angola. The vehicles on the chopper-pad belong to the troop of 120mm mortarists seconded to our base. The dirt road passing the base on the left makes a T-junction about 900 meters away in the vicinity of the green cuca shops just visible in the photo. It was from this T-junction that SWAPO would commence their attacks on the base by firing an RPG-7 rocket so that it would air-burst over the base. This was a signal for their 82mm mortars and 122mm rocket launchers to start firing.

The owner of the green cuca shops had bought a brand new 1988 model Mercedes 230 C. He was a local SWAPO supporter as were most of the local population. During one of SWAPO's attacks on Ombalantu, one of our mortar bombs fell near his car resulting in it being substantially damaged. The morning after the attack he pitched up at the entrance to our base and demanded to see the commanding officer. He demanded full compensation for the damage we had caused to his car. Captain Prins told him in no uncertain terms that it was his friends from across the border that had started the fracas and he should get his compensation from them. After this little incident we gave some thought to targeting his shop and car if there was another attack on the base. We would first drop one or two bombs in the general vicinity of his cuca-shop before switching fire to the enemy. In the end we never did it and I doubt if we ever really would have.

PHOTO 28

The white buildings in the photo were Ombalantu's post office and telephone exchange. It was a typical African post office. Time had no real meaning for the workers in or the people using the post office. It had one advantage though it was possible to phone home from it. After giving the number to be dialled to the operator, he would contact Oshakati from where a link would be made to South Africa. I often wondered if the South African military authorities realised how easy it was to get in touch with the outside world, directly from the border.

PHOTO 29

This photo was taken the morning after one of SWAPO's attacks on Ombalantu. One of SWAPO's 122mm rockets landed near the foot of the water tower. The surrounding area including some of the water tanks was peppered with shrapnel. 25-Field Regiment from Oshakati had to come out and install a new tank for us, the green one, and had to repair our walk-in fridge which was also full of holes.

The building in the foreground was our mess and kitchen. This kitchen served both as the officers' and enlisted troops' messes. Church services were also held in the troops' mess. The cultural differences amongst the peoples of Southern Africa came to the fore during one particular church service. A group of white artillerymen were stationed in our base for a short while. Everyone not busy with essential duties had to attend the Sunday morning church service. We duly began to sing traditional Afrikaans Hymns and Psalms. The troops had hardly begun to sing when everything suddenly became quiet. They all stopped singing at the same time. One of my sergeants quickly came over to me and explained that our black and coloured troops could not sing with the white troops as they had no rhythm and they sang in the typical Afrikaner, drawn out way of singing. I asked the white troops to fall in with my men and from thereon the service was a huge success. The harmonising and beautiful voices of my troops made singing in church a pleasure once again.

PHOTO 30

The red and silver roofed buildings in the centre of the photo belonged to the local branch of the SWA security police detachment. They differed from their SWAPOL-COIN (Koevoet) cousins in respect to their unit size and operating procedures. We used to liaise very closely with them. Any information relating to enemy activity that we received, we would share with them and vice versa. On more than one occasion we handed enemy spoor over to them after we were fortunate to find them. They were better equipped with their Casspirs to do a quick follow-up then were on foot.

Like most of the policemen on the border they were a wild bunch, but they got the desired results. They achieved better results than we in the Army ever did. Just before we arrived at Ombalantu at the beginning of the year a Koevoet team brought in a number of dead SWAPO insurgents. The mortar lieutenant from Charlie Company took out his camera to photograph the bodies when one of the security policemen told him to put it away. He did not comply quickly enough with the policeman's request, so the policeman walked over to him knocked him flat and broke his camera. Rank was not an issue with the police as it was with us in the army.

During the first enemy attack on our base the security policemen also returned the enemy's fire with 60mm mortars from their base. Unfortunately they had to fire over our heads to get at the enemy. Their aim was not all that good with the result that some of their bombs fell closer to us than they did to the enemy. Captain Prins was not to very pleased with this state of affairs and made his feelings clearly known to the policemen. One usually slept with one ear open on the border. The slightest unusual noise would wake a person. On more than one occasion we were rudely awakened by .50 Browning gunfire emanating from the police base. The gunfire was most often directed at dogs running around in the vicinity. It might have been fun for the policemen but it was not conducive to our state of mental health. The sound of a .50 being fired full-tilt in the still of the night could be quite frightening, especially when one was not expecting it. One never knew when it was the enemy attacking or the police shooting.

The two white buildings to the left and centre of the photo belonged to Julius Taipope the local Kwanyama headman. Taipope was a SWAPO supporter and informant. A good indication of a pending attack on the base was the absence of Taipope from his home for a number of days. When he left it usually meant something was going to happen. SWAPO would warn him to get out before attacking the base. Here I would like to point out the fallacy that SWAPO would indiscriminately kill their own people to terrorise them into supporting the movement. This never happened in our area of operations while we were on the border. The Ovambo people would support SWAPO of their own accord. It was not necessary for SWAPO to force them. The result of the 1989 election bears out this fact. The story put out by the South African authorities, that the Ovambo people wanted the SADF to protect them from SWAPO intimidation was not true. Quite the contrary. They did not want SADF or the South Africa government institutions there. How the South African authorities believed they could win an election in SWA when the military intelligence people on the ground, knew it was not possible is difficult to understand. The South Africa government cannot blame faulty intelligence for the election loss, as anybody on the border knew the degree of animosity felt by the local population towards the SADF and South African government. The South African administration must have known that they could not win the election. If the South African government knew this and I reiterate once again, they must have, why did they continue the war in SWA with its huge financial burden and the resulting loss of life? Thousands of people on both sides of the political divide lost their lives for nothing.

The twin row of fencing to the right of the photo encloses the minefield that was laid around the base. Thousands of R2M2 antipersonnel mines were laid around the base as protection against any conventional attack on the base by Cuban/FAPLA/SWAPO forces from Angola. On more than one occasion stray dogs would enter the minefield with fatal consequences. The trouble then, was to get the dead animal out of the minefield, as it was not possible to walk in and fetch it. If it was in the middle of the minefield we left it. Near the side we would try and lift it. The trouble was that the dead animals would attract other dogs and the cycle would be repeated. Before the minefield was laid we would place Claymore mines around the perimeter of the base as protection against a possible enemy ground attack. On more than one night Richard Schumacher and I slept on the chopper pad armed to the teeth, ready for the expected conventional attack from across the border. It never came. Only after the war would I discover the reason for this non-event.

Unknown to most people, South Africa had developed its nuclear capability to the extent that they had built six nuclear devices and were busy building the seventh. The National Party government of F.W. De Klerk terminated the project for fear of it falling into the hands of the incumbent ANC government of Nelson Mandela in 1994. Parallel to this Armscor was developing the ability to deliver the A-bombs by aircraft and/or SRBM (Short Range Ballistic Missiles). This technology was acquired from Israel in the form of the Jerico ballistic missile system. In South Africa the missile was known as the "RSA" and by the Americans as the Arniston. The missile system was developed further in South Africa and test-fired at Bredasdorp testing facility on the southern tip of South Africa adjacent to Cape Aghullas.

After the battles at Cuito Cuanevale and at the Lomba River in late 1987 and early 1988 Cuban and FAPLA forces started to advance southward to the border in the south western area of Angola, directly opposite western Ovamboland. This Cuban strategy immediately placed SADF and SWATF forces in the region of Xangongo, Techipa and Ngiva under direct conventional military threat. The South African forces were compelled to withdraw to positions south of the border inside SWA. This lead to a military vacuum in the southern part of Angola that was quickly filled by the advancing Cuban/FAPLA force. It was this force that ensconced itself just north of the border opposite Beacon 10 indirectly threatening Ombalantu and the interior of SWA. According to information available after the war, South Africa had informed the US government that it would use its nuclear arsenal against the Cuban/FAPLA forces should they cross the border and attack SWA. If this is true it meant that we at Ombalantu would have been directly involved in a nuclear war. Thinking back now, ten years later, it seems beyond belief that such a dangerous situation could have been allowed to develop in the region.

PHOTO 31

In this photo we see the "aap-kas" literally, monkey cage viewed from the officers sleeping quarters. Although an excellent observation point, it was seldom used, as it was unprotected and was clearly visible from a considerable distance. There is an interesting photo on p.155 centre left, of the same monkey cage in Al Venter's book "The Chopper Boys".

Most people are not accustomed to the sound of a modern jet engine. When one does normally work with such machinery, being near such a craft at an unexpected time and place can be quite terrifying. Late one afternoon Captain Prins was approached by a local Koevoet team with the request to arrange a casevac for an injured member of the local population. Captain Prins told the policemen that there was a public hospital three hundred meters away and that the SAAF could not be expected to send an expensive helicopter at night at the same time endangering the lives of its crew for a non military related injury. Apparently satisfied, the Koevoet team left our base and we settled down to our normal night routine. Later the night we retired to our sleeping quarters. Everything was quiet. The sentries were posted and our ops-room manned.

We usually slept lightly as there was the ever-present possibility of uninvited guests. Just after midnight we were awakened by a horrendous sound approaching out of the night. All of a sudden the sound started to shine a light on the base. It was then through my sleepy haze that I realised it was no alien from space but a Puma helicopter with its landing lights on. I couldn't make head or tail of what was going on. Rushing to our chopper pad I was just in time to see the Puma lift off and disappear into the darkness. Soon everything was quiet again. I was baffled!

After the police had been unable to arrange a casevac through the army channels, they had contacted their own HQ at Oshakati and brought in their own casevac, using our chopper-pad. It later came to light that the patient was not an ordinary member of the local population but an important police informer vital to police operations. The sound of the Puma's two jet engines in the middle of a quiet Namibian night was bone-chilling.

PHOTO 32 and PHOTO 33

These two posed photos are of Michael Smit demonstrating the two types of mortars used in our base. Photo 31 depicts the 81mm mortar and its bomb with its full complement of extra charges. The 81 was a infantry support weapon, mostly used by the infantry. Photo 32 is of the 120mm mortar and it's associated bomb. This weapon fell under the command and control of the artillery corps. The 120 had a range of about ten thousand meters when firing high explosive ammunition. Three 120mm mortars were stationed in Ombalantu in answer to the threat of Russian 122mm rockets.

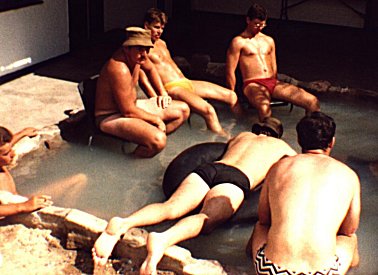

PHOTO 34

The officers never used the swimming pool in the base. We had our very own "paddle pool" in the centre of the courtyard of our sleeping quarters. Jan Theron our doctor built the small pool. It was promptly named "The Doctor Jan Theron paddle pool for tired officers". We usually dressed in regulation uniform "browns" from morning till midday. After twelve, dress code would be shorts and T-shirt. If we were not busy, most officers could be found cooling off in the paddle pool after lunch. Here we would discuss the day's most pressing issues, make the relevant decisions and talk about our future after the war. As there was no pump or filter the water had to be drained every third day or so and the pool scrubbed clean. We were lucky to have sufficient water in the base to keep the pool filled. The use of the pool was a great morale booster. Something so small had an effect much greater than its size belied.

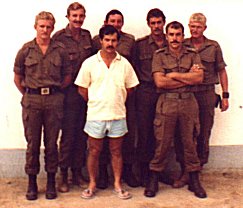

PHOTO 35

This was the last photo I took on the border, minutes before we set off on our return journey to Oamites and the end of our two years national service. From L. to R: 2.Lt Michael Smit, 2.Lt John Hammond, Capt. Willem Prins, 2.Lt Richard Schumacher, Lt. Armand Kruger, the writer and 2.Lt Johan van der Merwe. Up to a day or two before the photo was taken, most of the officers and their troops were still in the bush. It was my task to go and fetch them and bring them back to base so we could make final preparations for our return home. While involved in this task a strange phenomenon occurred. A number of the officers did not want to go home. They wanted to stay in the bush. It may sound strange but it happened. A person becomes conditioned to the life in the bush. Apart from the ever present danger of contact with the enemy there is very little else to worry about. There are no bills to be paid, no forms to be filled in, no phones to be answered and no bosses looking over your shoulder every five minutes. One becomes lulled into a false state of security. It was almost pleasant to be in the bush. This was a feeling most of us shared. The red lights were beginning to flicker for me. The danger signs were present. I realised that if we did not get a move on quickly, we would stay on the border of our own accord. I hastened the officers into the Buffels so we could get back to the base, and start preparing for the journey home. On the way back to base we fired off a large number of 1000 foot signal flares, left by Infantry School in our base. We wanted to see if we could hit an object in the veld from the moving Buffel.

Immediately after the photo was taken we said our farewells and I made sure all the officers got into the homeward bound Samil post haste. We were all sorry of leaving the company and especially Captain Prins. It felt as if we were deserting him. But I knew we had to break as quickly and cleanly as possible. I did not want anybody with second thoughts airing the idea of staying behind. We had done our share. We all had lives and loved ones waiting for us back in South Africa. We had to go, if we had stayed we would have been caught in a mental time warp, not wanting to go back and adjust to the normal world.

PHOTO 36

Ratel Golf-Five-Two-Lima played a central role in an incident that could have had far reaching international repercussions. During the later stages of 1988 the Big Five brokered peace process was in full swing, though we were not aware how of far the delicate process had progressed. In accordance with the peace plan all, SADF and SWATF forces were confined to northern Namibia. SWAPO for its part was supposed to stay north of the border and refrain from attacking targets in Ovamboland. They did not adhere to the peace-plan and kept on infiltrating and doing mischief in Ovamboland. A battery of 120mm mortars from the Artillery Regiment was posted to Ombalantu. The 120mm mortars were there to protect us from a possible attack from Cuban/FAPLA/SWAPO forces in Angola.

The artillerymen were in the enviable position of having three Ratel IFV at their disposal. Their officers, NCO's and troops were still new to the border having just arrived from the Republic. We considered ourselves old and experienced hands on the border. It was fun playing "GV" for a bit. Every few days, usually between seven and ten days, we would rotate our platoons in the field. We would take a fresh platoon out and pick the other up on our way back. We used our Buffel APC's to accomplish this task. Although the Buffel was mine resistant, it was not mine proof. With the Ratels in the base we hit on the idea of changing the platoons in the field with the help of the bigger and more mine resistant Ratels. Furthermore we saw it as a golden opportunity to show the "rookies" the real border as well as giving them a chance to pee in Angola. Their whole leadership assembly where national servicemen and their CO agreed that we could use his personal command Ratel for the task at hand. Their command element NCO's and officers decided to go along. `In for a penny in for a pound' - Richard and I reasoned. We decided that we would personally take them to the cutline. The two Buffels needed to pick up the troops would drive in the Ratel's tracks to avoid any mines. If a Ratel detonated a landmine it usually did not have the same fatal consequences for its occupants than when a Buffel rode over the same mine. The Ratel we rode in was a command Ratel and as such was only armed with a 60mm. mortar that could not fire due to a mechanical defect. The only other weapons we had were our personal R-4 rifles. This did not really bother us at the time, as we did not plan on being away for long nor did we intend to make contact with the enemy, after all we were on a routine trooping mission.

Richard Schumacher, who always enjoyed playing Rambo, volunteered to lead us to Beacon 10 after which we would proceed to fetch Armand and his platoon. This was Richard's big moment. He climbed into the Ratel commanders tower connected the intercom and radios and did a standard radio test. As Richard was a well-built man, he appeared to dwarf the Ratel and almost seemed to strap the Ratel on. He didn't climb in, he sort of `put it on'. Seeing Richard in the scenario, I could picture Rommel charging around in the North African desert forty-five years earlier. "Start up and go", Richard ordered. After clearing with the ops. room, one Ratel full of officers and two empty Buffels set off on the great expedition to Beacon 10.

At first, I was sceptical about Richard's navigation ability in the flat featureless vicinity of Beacon 10. Richard assured me that he knew exactly where to go. He seemed very sure of himself and I let myself be convinced. After reaching the Ruacana-Oshikati tarred road, Richard instructed the driver to proceed in a north easterly direction. I also knew the area very well and told Richard he was going in the wrong direction. He once again assured me that he knew exactly where he was and that he intended to approach the beacon from a different direction from the one we normally followed. He sounded very sure of himself so I let him be. How could I stop him now that he was enjoying himself so much? Nevertheless, the funny feeling I had in my stomach that something was not right, refused to go away. The area we were driving through was unfamiliar to me but I did not want to say anything to Richard at that moment, in case the artillerymen realised we were not the great bushfighters we had made ourselves out to be. Soon Richard was leading the convoy to the left and then to the right. It did not take him long to bring the small convoy to a halt. With sheepish eyes he turned around and looked at me. He did not have to say anything, I knew.