Chapter Three

Transferred to the Army Service Corps

The journey was relatively short, as our destination proved to be Army Services School, also in Voortrekkerhoogte, and here our real army experience began. We had hardly pulled up when we were greeted by a bunch of screaming Corporals, all Afrikaans, who seemed to take offence at the slightest word or look from any of us recruits. We were first bullied into a line outside the barber and, with little ceremony and a lot of shouting, shorn of even the short hair we thought we had already cut so neatly a few days ago, and then chased at double time to the stores, where we were issued with our uniforms, kit and rifles.

The stores ritual is a saga in itself, and well worth describing. In a sane world, you would go into a store, get an item of clothing and try it on to see that it fitted you properly. But in the army you were accosted by some sharp-eyed stores Sergeant who would look you up and down briefly, as if you were some kind of dead meat, and throw a couple of nutria shirts, trousers, jackets, a jersey, webbing and ammunition pouches, ground sheet, PE gear, boots, shoes, dress uniform items, belt, water bottle, helmet and bayonet frog at you, without so much as a second glance - and God help you if you suggested that his judgement as to your shape and size was perhaps amiss, once you had tried on the shirts and found them to be too short or too long! Those of us with mismatched clothing very quickly swapped what we could with others in the same predicament, rather than incur the wrath of our Corporals or the Sergeant.

Once we had received all of our kit, we were issued with a 7.62 mm R1 rifle, plus a cleaning kit for it, and then we were unceremoniously hounded back onto trucks and driven out of Voortrekkerhoogte, and eventually Pretoria, and onto the Rustenburg road. By this stage we were wondering what the hell was going on, but after what seemed an hour we turned off the main road and onto a dirt, or metal road, leading into the veld. Another uncomfortable few minutes passed in the back of the trucks until we came out at a camp, literally hacked out of the surrounding bush. This was Elandsfontein, a sub unit some 25 miles outside of Pretoria and attached to the Army Service Corps (ASC). It was the home of the ASC's Catering School. In short, we were to be turned into chefs, or cooks!

Even now I cannot adequately describe my disgust at this turn of events; after all, real soldiers didn't cook food, they either shot people or stitched shot people up! Again, I am talking of my reaction as a 17 year old, for that is how old I was at the time. All my old desires to be transferred to the infantry resurfaced in a rush, and I felt like crying, I was so low.

These thoughts didn't remain for long though as our screaming Corporals hounded us into one of the unoccupied prefabricated bungalows, and it was every man for himself as far as a bed and `kas', or cupboard were concerned. I lagged behind in this rush and only managed to grab one near the rear end of our bungalow, No.3, where I threw my gear and sat down despondently, wondering what else could go wrong. Plenty could, and would of course, but I still believe I was fortunate in my ultimate vocation and service, although I would not have chosen to do so then, or now, given the opportunity again.

Army Catering School, Elandsfontein

Elandsfontein was a relatively well built camp, but also quite new and isolated, and it had none of the basic facilities that the recruits at Services School in Voortrekkerhoogte enjoyed. It was so isolated in fact that one could hear the jackals and other wild animals calling to each other, just outside the fence line at night! The camp, rectangular in shape and surrounded by an eight foot high wire fence complete with main gate, was quite Spartan in layout. At the one end there was a vehicle park, where all the unit's trucks, cars and other vehicles were kept. In front of the vehicle park were the mess halls and the kitchens, the latter equipped with both fixed stoves and ovens, and army field kitchens, as we would learn to cook under field conditions also. Next came the Commanding Officer's and other offices, in front of which was a small garden and next to which was a small parade ground. Then we had the barracks or bungalows, placed in two neat rows, with a toilet and communal shower block off to one side of these. These latter two deserve a better description, as they would have a profound effect on the health of a number of us at Elandsfontein in the winter of 1978.

The toilet and shower block was a brick building with corrugated iron roof, but it had a series of open slots along the top of the walls, between roof and walls, that were entirely open - no windows of any kind. This meant that the inside of the shower block was entirely exposed to the cold at all times, and were pretty chilly to visit, even in the middle of the day. To top it off, there were no hot water facilities at Elandsfontein at all, all water having to be pumped up to the camp from the main water pipe near the main road, This meant we had to wash dishes as well as ourselves in ice cold water, in the middle of winter.

The same bare dimensions applied to the barracks, except that these were rectangular bungalows housing one Platoon each, or about 30 men. Their walls were manufactured out of single layer prefabricated board, with no insulation and there were no windows in these either. Instead, the gap between the walls and the roof, approximately one foot in span, was filled with metal grills, which doubled as windows / ventilation, but were entirely open to the elements at all times. There was a door at each end of the bungalow, and beds along the length of the each wall, with a steel cupboard next to each bed.

Beyond the bungalows, was the main parade and exercise ground, a dusty flat space raised slightly above the level of the rest of the camp, so you had to march up to it. As you approached the parade ground, there was a water tower located in the top right hand corner of the parade ground, which we came to know intimately in the next few weeks.

In time, we would come to call it Elendesfontein. (lonely or miserable fountain!)

Basic Training

I found myself and the rest of my new comrades were now part of Platoon 2, and as such we were to do everything together. Our platoon instructors were two sadistic little Corporals, Steenkamp and Jordaan, who were just beginning their second year of service, having started their National Service in July 1977. All of the Corporals in the camp were National Servicemen like myself, but had been through an NCO instructor's course during the preceding year and were now back at Services School to train new recruits.

I had my fair share of run-ins with Corporal Steenkamp in the coming weeks, but overall I found him to be fair, even at the time. Jordaan was a completely different matter. He was a jumped up little shit from a small town (Standerton), who believed that his new found authority, granted him at the end of his NCO's course, was a licence to do whatever he pleased to any recruit, whether legal in the eyes of the military or not. When I think back on him now, I still hope that he came to some nasty mischief eventually, as it was the least he deserved. In my two years National Service I found the army to contain a number of objectionable characters, but Jordaan was the worst of them that I encountered. He delighted in torturing all of us, often beyond the letter of the law, and was eventually caught and punished while we were still undergoing basic training.

His basic pettiness surfaced not long after we were transferred to Elandsfontein. The barber would come around to the camp once a week from Pretoria, and anyone requiring a haircut would then be told to report to the barber. Despite all of us having all been fairly shorn already, Jordaan decided that our hair was too long, and he marched the entire Platoon off to the barber one day, and ordered him to give us all a crew cut, or marine style haircut. We were all basically bald at the end of this, and the laughing stock of the rest of the Company - until Lieutenant MacFarlane found out. He was furious, and gave Jordaan a tongue lashing second to none, unfortunately all too late for our hair or dignity. It took a long time for the hair to grow back too, and I still have a photo, taken by my mother on a visiting day almost a month later, where my very thin top is obvious - this after a month of growth.

Basic training itself was worse than anything I had imagined it would be, and yet in hindsight I am glad I completed it. It gave us all a wonderful sense of comradeship and achievement, which is I suppose the aim of the exercise.

Platoon 2, Services School National Service Intake, Elandsfontein - July 1978. I am standing in the back row, second from the right.

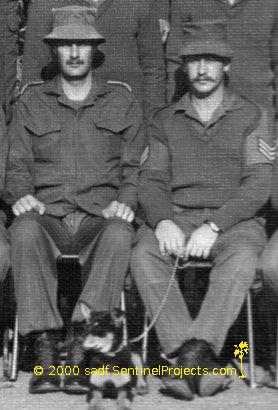

Our two Platoon Corporals, D. Steenkamp on the left and H.J. Jordaan on the right.

To start at the beginning though, we were informed that we were part of a Company, at Elandsfontein, approximately 180 men strong, all of whom would be trained to be chefs. Many had been posted to the Army Service Corps in Voortrekkerhoogte right from the start, and had been sent to Elandsfontein at least a week before we transfers arrived via the SAMS. We were briefed on what was expected of us, and what we could expect if we failed to comply. This briefing was given by our Company Commander, Lieutenant McFarlane, who was one of the few permanent force soldiers (PF's) at the camp. We were all afraid of him to start off as he was every bit as fierce as the Corporals, but he was quite a fatherly figure under his gruff and serious exterior, and always had our welfare at heart, even if he did have a funny way of showing it at times!

The Company Sergeant Major, a misnomer surely given his actual rank, was Sergeant Janse van Rensburg, another PF who was always immaculately turned out, even in his brown nutria uniform. He had a quite manic expression, and frightened the hell out of me most of the time, but I was to be eternally grateful to him one day, as he saved me from serious harm in a most unexpected way. Janse van Rensburg was very quick to punish even the slightest infraction by us, usually by delegating the task to one of the Corporals, but I was filled with admiration for him from the start, as he set out to show us that he could do anything he asked us to do, which is more than either of our platoon Corporals ever managed! It came about at a PT session, where he joined in with the Company and did all the press ups, push ups, sprints etc., that we were asked to do, and in less time than it took any of us to do so! He was no youngster either, being married with teenage children as I was later to discover.

Lieutenant MacFarlane (left) and Sergeant Janse van Rensburg (right). The dog belonged to the Sergeant and followed him everywhere.

Each platoon was commanded by two full Corporals, both National Servicemen, and there were sundry PF's working in the kitchen, plus a few National Service Privates. I wasn't aware of it then, but the latter were the top candidates from the previous intake (January 1978) and were destined for promotion to Lance Corporal, and to become our instructors during second phase basic training. We had nothing to do with them at first though, as all our training was undertaken by our platoon Corporals.

The last two instructors we had to deal with on a daily basis were our two PTI Lance Corporals, who gave PT to the entire Company. PTI's, or Physical Training Instructors, had to complete a special PTI Instructor's Course, at the conclusion of which they were awarded a single rank promotion, to Lance Corporal. After a time they were promoted again, to Corporal, depending on their performance. Our two were positively mad, but as fit as hell, and they were very hard on us initially. Over the years I have forgotten their names unfortunately. The PTI's made an interesting contrast, as one was swarthy and had black hair, and the other pale faced and blonde.

Once at Elandsfontein, our fellow recruits already there gave us hasty instructions on how we were expected to lay out our uniforms, beds and equipment for inspections, and how to polish our boots. For the purposes of training, we were issued overalls, and had to wear these throughout our basic training, instead of our uniforms. We also wore the plastic inner from our helmets, rather than berets, bush hats or full steel helmets. This plastic inner was known as your `doiby', and was hated by us all. It all seemed silly to me at the time, and still does. What was the purpose of giving us helmets and bush hats if we couldn't wear them while undergoing what is in effect basic infantry training? All of our instructors and officers wore bush hats each day, as we were effectively being trained in field conditions.

Polishing boots was another interesting exercise, as it wasn't just a case of slapping on the polish and buffing the boot until it shone. We were required to `bone' the toe piece of each boot, as well as our dress uniform shoes, besides polishing the rest of the boot or shoe to a gleaming shine. Boning entailed vigorous application of a number of layers of polish to the area you wished to shine, and then rubbing this until it was as smooth as glass and shone as brightly as a mirror. It was as difficult as it sounds, and we spent many hours each night just doing this, in an endeavour to avoid the wrath of our Corporals. Mind you, it looked impressive as you could literally have shaved yourself, using your boots as a mirror, if you had wanted to.

Our actual basic training, delayed due to our late arrival at Elandsfontein, began on Monday 17th July, and I got off on the wrong foot straight away! Perhaps it was my height, as I was taller than many of the others in Platoon 2, and I stood out when we were on parade or standing inspection, but my first two dawn inspections were a disaster. For no reason that I could see, Jordaan threw my bed over and screamed at me, and on the Monday in particular I spent most of the day doing afkak, or punishment of one kind or another. In fact, as a consequence I ended up at No.1 Military Hospital two days later for x-rays, as I hit one knee rather badly on a rock during all this afkak. The damage proved to be superficial and all I got for my trouble was a couple of days light duty (no afkak!). Of more interest, I met my brother David at the hospital, as he was also having x-rays - on his back! He told me that our parents were concerned as they had still not had any of my letters since my move to Elandsfontein, and the bloody army had not bothered to inform them where I was either! Our fortuitous meeting meant that he could call and let them know where I was, so some good did come of my visit to the hospital.

I suppose the best way to describe what basic training was like, is to describe an average day, and then perhaps some anecdotes. Our day generally started at about 4.30 am, when the camp generator was started and we turned out of our beds to prepare for inspection. This was a daily routine during basic training and much feared by us all. No matter how hard we tried, we seemed to always have missed some minor detail, or left some fine film of dust on something, for which we would be punished. From Mondays to Thursdays, inspection was carried out by the platoon NCOs, and on Friday mornings we had full uitpak inspection, which was taken by either our own Company commander, Lieutenant MacFarlane, or another more senior officer from Services School, who would travel to Elandsfontein from Voortrekkerhoogte for the privilege.

At about 6.00 am the Corporals would come through the barracks and do their inspection, turning over beds, throwing our equipment around and generally making our lives a misery. If your equipment or person were considered to have failed inspection, you were put on a charge and had to appear `on orders' before the Lieutenant. This was usually just after lunch the same day, when the defaulters were marched, one at a time, into the Lieutenant's office, there to be dressed down in no uncertain terms and given a punishment. This could range from the dressing down itself, to further punishment PT, depending on the severity of your so-called 'offence'. The latter were usually minor in nature, such as a dusty pair of boots or a slight crease in your bedding, but were punished fairly severely all the same.

There was a perception in the South African Army at large, that soldiers assigned to chef training were generally soft and probably gay, hence the `easy' posting they received. Before I became one, I was guilty of this perception as much as anyone at the time. The truth was very different though, as our numbers were allocated on a needs basis only, with no regard given to our ages or education, and we were all fit enough to have served in the infantry if required. As far as I am aware too, I don't think any of us were gay! To make matters worse, our instructors were well aware of the lack of esteem we were held in by other arms of the service, and went out of their way to see that we were a harder bunch of bastards than even the infantry were. Nobody was allowed to make any disparaging remarks about chefs around our instructors, and that included us. They made great store of informing us that the infantry were the really stupid bastards, as they were too dumb to train at anything else! In time, I came to realise that this too was an unfair statement born of ignorance, and I ended up with more than a sneaking respect for the PBI (poor bloody infantry) in my later service.

As strange as it sounds, we used to look forward to the officers' inspection on Fridays as, although the Corporals accompanied the inspecting officer on each occasion, the officer decided whether your inspection was up to scratch, and they were generally more lenient than our Corporals. This wasn't always the case though, one occasion being particularly notable! A certain Services School Commandant, who shall remain nameless, came to take inspection. We were always given advance warning of who would be taking Friday inspection, and this occasion was no exception. One of the guys doing basics with us was delighted as the Commandant was no less than his uncle, and he spent most of the week telling us just what a nice guy his uncle was. Well, come Friday we discovered just what an arsehole he was instead! Having already inspected some of the other bungalows, the Commandant duly arrived at our bungalow and we all stood rigidly to attention as he went from one person to the next, finding the most niggly things wrong with each inspection, and placing all of us on a charge - the entire platoon! In my case, it was because he found dust on my helmet, or so he claimed. I could not find any straight afterwards. You weren't allowed to complain of course, and we merely stood to rigid attention and starred ahead while the Corporal, in this case Jordaan, took down each name in turn. I'll always remember the look of absolute disgust on his face though, and he was strangely quiet about our supposed transgressions, when normally he would have jumped at the opportunity to punish us all. We discovered why soon afterwards, when we were eating breakfast. It seems that the Commandant went through all six bungalows and placed all of their occupants on a charge for failing his inspection, all except one man that is. No prize for guessing who this was either - the Commandant's nephew! I have never seen such bald faced cheek, before or since.

Our Lieutenant was furious at this favouritism, especially as he was no doubt well aware that we could not possibly have all failed inspection, with one exception. Being outranked though, there was nothing he could do about the injustice. We were paraded that day after lunch and informed that our punishment for failing inspection would be to all stay in camp for the weekend (this particular inspection was held some two months into our basic training, by which stage we had begun getting semi regular weekend leave passes). The one exception was the Commandant's nephew, who was given a leave pass for the weekend, more for his own safety than because he had passed his inspection, although the latter was the official reason given. I think the Lieutenant thought that some of us might harm him if he stayed in camp! What the Commandant failed to appreciate was that his nephew was there for his whole basic training, and after this little episode the Corporals made his life hell!

To get back to the average day though, following inspections we had to form up in our platoon, where a roll call was taken by the Corporal. Your options here, when your name was called, was to acknowledge your existence if you were fine, Ja Korporaal ! (Yes Corporal !), or to report yourself as ill if you were not, when you would be ordered to report to the visiting doctor after you had eaten breakfast. The doctors came each day from Voortrekkerhoogte. A few of us tried this as a way of getting out of the punishments we knew were coming, but if you were discharged by the doctor as being fit, when you had reported sick, your punishment was usually a lot worse! Personally, I never did, always making damned sure I was either sick or injured before I reported myself as such.

Once through roll call we were marched off to breakfast, and then formed up again afterwards to march up to the top parade ground, where we would drill for the rest of the morning, until morning tea anyway. I used to enjoy drill when it all went well, but initially, while we were learning, it didn't of course, and then we would get chased around by the Corporals again. One of their pet hates was men marching out of step, and we had one unfortunate in our platoon, J.J. Eckley, who seemed to make a habit of this. As a result we all got punished more than we would have liked and poor Eckley got cuffed around the ear by some of the rougher guys in the platoon when the Corporal wasn't looking too closely. One of the favoured ways of punishing us during drill each morning, was to drill us at double pace, which felt like you were running at times, or chasing us around the water tower.

After morning tea, we would again parade briefly before the Lieutenant's office, for any announcements, and then we had lectures in our platoons, given by our Corporals again. These often were just another excuse to give us more punishment PT, in the guise of `training'.

The unfortunate J.J. Eckley, who had two left feet when it came to drill.

On one occasion Corporal Jordaan decided that we needed to practice an attack on a strongly fortified enemy position. For this, he chose a typically rocky piece of open veld outside the confines of the camp, and his instructions were simple. To simulate enemy fire he would blow his whistle, and each time he did so, we were to drop full length and take cover, before crawling along on our elbows, rifle safely cradled in your outstretched arms in front of you. The latter was known as leopard crawling, as you laid as prone as you possibly could and dragged yourself along on your knees and elbows. When the whistle blew a second time you had to get to your feet as quickly as possible and attack once again. We were wearing basic webbing and had our helmets on for this exercise, and each time we charged across a particularly stoney or rocky section of the ground we were attacking across, he would blow his whistle, and we had to dive headlong for cover. Many elbows and knees were scraped or bleeding after this had happened a few times, but the more of us who were injured, the more Jordaan seemed to delight in it all.

To make matters worse, I had consumed a large amount of tea at morning tea, and was rapidly becoming aware of an urgent need to urinate. I brought this to his attention at a suitably moment, but his response was to scream at me once again and order me to piss in my pants if I needed to. I held on as long as I could, but in the end common sense prevailed on my part, and I did just that! I remember thinking that I just didn't care any more, and as perverse as it sounds, I was so exhausted and worn out, that relieving myself like that was wonderful. Besides, I was so filthy and covered in dust (we all were) that it was barely discernable among the general grime I was covered in. I think Jordaan was horrified, but his response was muted, no doubt aware that he had, once again, overstepped the mark by refusing me permission to do something as basic as relieve myself. He merely told me to change myself when he dismissed us at the end of the training.

Leopard crawling, while being harassed by our Corporals (standing left and right). Who said an army Chef had an easy life in basic training?

Late morning lectures were followed by lunch, which was always welcome due to the excessive amounts of physical activity we had done during the morning. In all my time in the army, the food was good, and I don't just say this because I was a chef myself. We were given balanced meals and could always top up with bread or whatever else we could scrounge around the camp and mess. Some guys used to stuff their pockets with sandwiches, to eat later, as our mealtimes in basic training were kept short.

The biggest problem we had at Elandsfontein was the lack of basic facilities, like hot water for washing and showering. As we were in the field, there was none of the niceties of plates, bowls and cutlery, as supplied at many permanent base camps, like SAMS Training Centre and Services School in Voortrekkerhoogte. We were expected to use our field implements, which consisted of our dixies, two aluminium half containers that fit one into the other and had a collapsible handle, and our knife, fork and spoon set. As a result you tended to get the food mixed up into a big mess, before you had time to begin eating it, but it all tasted the same so didn't bother me personally. We had to wash our own eating implements and dixies after meals, and then were given no soap of any kind to do so. We improvised as best we could, using toilet soap and cold water, mixed with some grit or sand if the meal had been particularly greasy (Irish stew!), but without hot water our dishes were no doubt covered in germs, and this led to frequent bouts of the trots, or diarrhoea, which we all suffered from at least once. Diarrhoea was no excuse for not doing training though, and we just went along with the cramps and relieved our protesting bowels as best we could in our breaks!

After lunch and another short parade in front of the Lieutenant's office, it was back to the lectures again. I recall that the afternoon lectures were more inclined to involve actual lectures. In the initial stages of our basic training, we covered such riveting subjects as rank structures in the SADF, rank recognition in different services (Army, Air Force and Navy) and which was equivalent to which. I remember that the naval ranks were all out of whack with the other two services, and didn't even look the same, and I still don't understand them properly to this day! An old friend from my school days, Gary Hodge, had joined the Navy as a PF, and risen to the rank of Ensign, which is some junior officer, but this was about the extent of my knowledge. I didn't pay much attention either, thinking I'd never come across another naval rank as I was in the army. How wrong can you get!

Not paying attention to these afternoon lectures got me into serious trouble with Jordaan yet again, as one day, following a particularly trying morning where I had been punished twice already, I fell asleep during his boring afternoon lecture. It was a hot day, despite being winter, and I just couldn't keep my eyes open. Sadly for me, I was spotted dozing by Corporal Steenkamp, and my punishment was set for later that afternoon, when everyone else had been excused for the day. It was Wednesday afternoon, and we enjoyed `sports parade' each Wednesday. In reality, we rarely did any organised sport as there were no facilities at Elandsfontein and it was too far to travel to Voortrekkerhoogte. Anyway, on this day I was ordered to appear before Jordaan after afternoon tea, resplendent in my full kit with helmet and rifle. My kit was filled with wet sand, making it feel five times heavier than it normally was, and I was then put through an exhausting series of punishments, which included rifle PT, infantry attacks done to the whistle again, push ups, sit ups and pole PT. After what seemed a lifetime of this, I was utterly stuffed and broken in body and spirit, and I collapsed. Jordaan screamed at me to get to my feet, which I was completely unable to do, and his response was to grab my rifle and hit me in the head with it. He hit me bloody hard too, and it was lucky that I was wearing my helmet as I'm sure he would have fractured my skull if I had not been. I was crying, more out of frustration and sheer exhaustion than anything else, and I just could not stand up. Once Jordaan realised that I was not faking, he called over two men from my platoon and ordered them to carry me back to the bungalow. I remember that one of them, Dick, was furious on my behalf, as they had to literally carry me right into the bungalow and lay me on my bed. I was just too exhausted to care, and it was some hours before I was able to stand up on my own again.

The general order of events though, once afternoon `lectures' were completed, was a quick afternoon tea followed by PT. The latter began at 4.00 pm on week days and, as previously mentioned, was conducted by our two PT instructors, both Lance Corporals. We would hastily return to our bungalows and change into PT gear, which consisted of shorts and a singlet or T-shirt, plus sneakers, and then assemble in a company sized squad on the main parade ground.

Private R.M. Dick

Our first few PT lessons were hell, in a word, as we just couldn't seem to do anything right or in time, and spent the whole lesson doing afkak again. Right through basics, every PT session started with a 2.4 kilometre run, 1.2 kilometres from the parade ground along a route that took us outside the camp and up the main road towards civilization, and back again once we reached a rock that had been painted white as a marker. For starters, we were informed we had to run this, and if anyone was caught walking, then all of us would run this again. Needless to say, in the early stages of basic training, we were all very unfit, some more than others, and someone was always being caught while walking to catch their breath. I was never caught, but did stop to catch my breath on occasion, so I was as guilty as the others less fortunate, who were caught. The end result was the same though - we all did it again! The same went for our other PT disciplines, which included the usual push ups, sit ups, squats and the like, as well as short sprints. The latter were done around the water tower at one end of the parade ground.

The first time we were sent on a run around this tower, we were told we had to do this in 13 seconds. That included breaking from our company squad, sprinting around the tower and back, and reforming into company squad. It was laughable to even suggest we could do it in 13 seconds, and must have been very funny to watch us try. However, it wasn't funny trying to do so and we took at least ten seconds longer than the allowed time initially. Time was taken from when the last man reformed into the squad, and the company had a few fattys, who lagged behind always. Initially we just left them to their own devices, but when it was made clear to us that not having to redo something depended on these same fattys completing it in time, we took to dragging them along with us. A clever way to teach teamwork! Like most teenagers, we hadn't given the thought of teamwork any consideration at all and were only interested in ourselves until we got to the army. After a couple of weeks of not being able to get back in the squad in time, we challenged our PTI's to prove that it could be done. They just smiled and agreed, with the proviso that we would receive extra PT if they did in fact run the tower in under 13 seconds. They ran it in 11 seconds flat, and after more sweat we learned not to question their judgement again!

Push ups, one of the favourite punishments, were handed out regularly for the most minor infraction, and it wasn't uncommon to be told to "give me 50" by any Corporal. In the beginning, this too was more a matter of luck than anything else, but after a few weeks we could all do 50 push ups, and more than once a day too!

The end of any day's lectures and drill was signalled by the end of PT, but the day was far from over! We were given time to shower and then had to form up in our platoons, to be marched to the mess for dinner. Once dinner was over, it was back to your bungalow to prepare for the next day's inspection, and write letters etc., if you could spare the time.

Initially this work on your equipment used to take up most of our spare time in the evenings, as rifle and kit inspections were strict. Once we had the basic groundwork done though, like the fine boning of our boots, we could relax a little more. Our Corporals soon found other ways to occupy us though, and we would be called at odd hours to do afkak, usually for some imagined misdeed, leaving us little time to prepare for the next inspection before lights went out at 10.30 pm. This was a regular feature too, as the generator was turned off at 10.30, ending all power (and therefore lights!) to the camp.

Friends, and other strange creatures

At Elandsfontein I quickly latched on to a fellow `roof', Clyde Birch, who although not in my platoon, became my best mate while there. He was something of a rough diamond and came from Germiston. Like me, he was engaged to a girl back home and we used to spend our limited spare time having a furtive cigarette, or discussing our fiancees, and what we would do when out of the army.

Clyde was inclined to get into a fair amount of trouble with the NCO's particularly, and very quickly acquired the nickname "Beelzebub", after the demon of the same name. He wasn't particularly nasty, but was an active marijuana smoker and the Corporals were always trying to catch him with the stuff. They never did though, as Clyde was way too smart for them and hid his stash well. It helped him to be a bit of a pot head, as on one famous occasion. His platoon had just been screamed at by their Corporal and Clyde muttered, "Fok jou Korporaal" (Fuck you, Corporal), under his breath, thinking the Corporal could not hear him. He was wrong, and a bevy of angry NCO's descended on him, screaming obscenities at him. In due course, Clyde had to report just after lunch in his full gear, filled with wet sand, as well as his rifle and helmet, and was given the same afkak that I had already endured on an earlier occasion. The whole time he was being punished, he had to shout out, "Fok jou Korporaal", continuously. I think they were hoping to break him to the point that he couldn't say it anymore, but they'd reckoned without Clyde. Knowing what was coming, he spent his entire lunch break safely sequestered in the vehicle park, smoking a very large marijuana joint, and by the time he reported for his afkak, he was as high as a kite. He spent the next two hours being chased, dragged and kicked around the camp and surrounds, the whole while shouting his obscenity at the Corporal, but never once wavering. To top it off, he had this goofy smile on his face the whole time, which drove the Corporal almost mad. In the end they just gave up on trying to punish Clyde, and dismissed him back to his platoon.

On the other side of the coin, there was an Afrikaans youngster in my platoon, Jacobs, who was always bumming cigarettes from me, and anyone else who would give him one. As soldiers, and National Servicemen at that, we were paid only a pittance, my in-pocket pay being about R42 at the end of the month. This left me with enough money to buy three cartons of cigarettes, some boot polish, stamps, writing paper and envelopes, and little else! I was writing to a few people, and to my fiancee daily, so this was not an inconsiderable expense, even if postage was only four cents for local letters in those days. Anyway, being friendly, I did give this young lad more cigarettes than I probably should have, and while others stopped being so obliging, I continued to do so. I eventually cottoned on though, as I realised he was spending his pay all on pay day, and then on crap, like chocolate bars rather than the cigarettes he obviously craved. He wasn't too friendly when I declined his next request for a cigarette, as by that stage he had burned all his bridges and nobody was prepared to share a cigarette with him!

Perhaps the oddest man I encountered in my basic training was Corporal Westernberg, a PF who was assigned to our platoon and did basic training with us, suffering the same verbal and other abuse that we endured from our National Service Corporals. He kept very much to himself and fraternised as little as possible with us, spending his evenings preparing for inspections and writing letters home to his wife. We were puzzled as to his inclusion in basic training, but discovered afterwards that completing basics again was part of his required training for promotion to Sergeant. He only completed the three month first phase basics with us, and then returned to his unit elsewhere, having achieved his promotion no doubt.

Private Jacobs (left) and Corporal Westernberg (right).

Guard Duty

Being in the army, we also had regular guard duty details to perform at night, at least during basics (first and second phase). I used to love these, even though they meant less sleep and a tiring day the following day. The main reason was that we didn't have to stand inspection on the morning following a guard duty, and as one of the few who freely volunteered to stand guard, I managed to get out of a few sticky inspections over the six months I spent at Elandsfontein. Guard duty was allocated by platoon, and you were merely advised that you had drawn duty. The drill was to report in your webbing with rifle and bayonet, after dinner, at which point the guard commander would march you to the guard tent, located near the main gate. We performed guard duty at a few locations around the camp, including the vehicle park, main gate and perimeter fences.

The guards were given a large urn of coffee for the night, as well as a couple of boxes of rusks, another reason to volunteer for guard duty. One thing I could never get enough of during basic training was food! Clyde and I stood guard duty together regularly, and liked to draw the 2 am to 4 am shift. That one was in the dead of night, and you could almost guarantee not being disturbed, as most of our Corporals had gone to bed by then. The downside to this was the intense cold, as it was mid winter. You could watch the frost forming on the ground! Initially, it was also eerie as the jackals were active at night and could be heard, and sometimes seen in the form of a pair of gleaming eyes, just out of reach of the light of our gas lamps. One particularly cold morning Clyde lit up one of his joints, and offered me a few puffs, as he always did. Usually I declined but this time I accepted, as I was so bloody cold! I'm glad I did too, as it left me with a nice warm, numb feeling and I never noticed the cold after that!

Even at night, the Corporals found ways to make our lives difficult, like snap inspections to check that you had all your proper equipment, and that your bayonet was fixed to your rifle. We weren't issued with any ammunition, which was probably just as well as we were likely to have shot and killed a couple of our Corporals at the least! One night though, when I wasn't on duty fortunately, the latter decided to make a sneak attack on the camp, and they took the guard detail by complete surprise, with one exception. On being unexpectedly confronted by one of the Corporals, each sentry in turn meekly surrendered his weapon and was consequently put through further afkak the following day, for being inefficient enough to be caught short by unarmed `enemies'. The one exception was the aforementioned Private Dick, from my platoon. He was on duty with another man at the vehicle park when the attack took place, and hearing the muted commotion, he took cover behind one of the vehicles. He was eventually found by a Corporal and told to surrender his weapon, but refused to do so, insisting that the Corporal come and get it if he wanted it. We all thought Dick was sure to get crucified the following day, such was the anger directed at him by the Corporals, but he was the one sentry who didn't get punished the following day, as he had been the only one to put up a fight, albeit a symbolic protest at best.

Dick took this one step further on another occasion, when he was guarding the main gate over the weekend. I should point out that we stood sentry duties at night only during the week, but on weekends we had to do so round the clock, two hours on duty and four off. One Sunday our Company commander, Lieutenant MacFarlane, drove up to the main gate in the middle of the day. Being a PF, Lieutenant MacFarlane went home each night and on weekends, and so it was unusual for him to be at the camp over the weekend. He was wearing civvies, and had come back to the camp to fetch something he had forgotten there on Friday afternoon when he'd gone home. Orders were that nobody could get into the main gate without proper military identification, which we all carried. This was a small book with your photo and other details, and had to be presented on demand. Anyway, MacFarlane drove up to the gate and hooted at Dick to let him through. Dick refused, and stood his ground, refusing to open the gate. Instead he approached the car and asked MacFarlane very politely for some identification! By now quite exasperated, MacFarlane pleaded with Dick, saying that the latter could surely see it was him. Dick was adamant though - no proper identification, no entry - and to make his point he raised his rifle menacingly and threatened to bayonet MacFarlane's front tyre! MacFarlane had no choice, as he had not thought to bring it with him, so cursing Dick he turned his vehicle around and drove home, all the way to Pretoria, to fetch his ID, before returning to the camp.

We all thought Dick had really gone too far this time, as it was one thing to piss off the Corporals, but MacFarlane was God at our camp, being the highest rank, and could do anything he liked without much fear of recrimination. On Monday Dick was taken to the Lieutenant's office `on orders', and we waited with bated breath to see what punishment he received, imagining the worst of course. We were amazed when he emerged with the biggest grin on his face I'd ever seen, and the news that he had been praised for his devotion to duty, and been awarded an extra weekend leave pass as a reward!

At the end of July, we were finally allowed family visits at Elandsfontein, and I hastily wrote home and asked everyone to visit me. My mother drove through on the weekend of 29/30 July, bringing my sisters, plus my fiancee Sharon and her sister Sonya, plus a lot of food and other goodies. It was fabulous to see everyone again, and weekend visits became a lifeline to me when I was feeling down or pissed off at the army. I would just think of the visit just gone, or one coming up that weekend, and it would cheer me up.

The visits themselves were restricted to the hours of 1.30 to 4.30 pm on Saturdays and Sundays, and followed the time honoured format. Your relatives would arrive and announce themselves to the guards, who would fetch you from your bungalow. We were allowed outside the camp perimeter, as there was no space in the camp to receive visitors, but we had to remain within sight of the camp at all times. The rather restrictive conditions made us all long for our first weekend leave passes, which at this time were still to be granted.

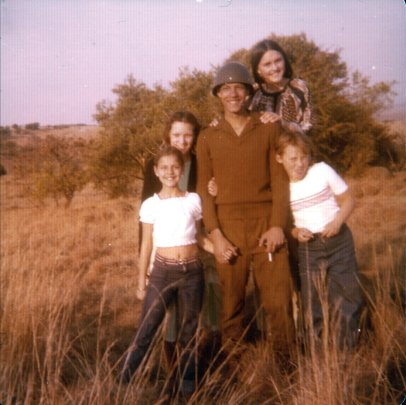

Visitors at Elandsfontein at the end of July. On my right are my youngest sister Melanie and Sharon, my fiancee, and to my left are Sharon's sister Sonya and my other sister Heather.

1 Military Hospital, Voortrekkerhoogte

Early in my basic training, a series of related events were to have a depressing effect on my health, and that of a number of the other men doing basic training at Elandsfontein. As a result of these, I, and many others, ended up in No.1 Military Hospital in Voortrekkerhoogte, suffering from pneumonia.

I have already alluded to our primitive facilities, which included cold showers and open buildings, none of which were very good for our health in a cold winter. Shortly after we started basic training, Sergeant Janse van Rensburg took exception to the state of some of our toilets, which had been soiled by unknown National Servicemen and not cleaned properly afterwards. The consequence was that we were forbidden to use the toilets at all. Instead, we were made to dig six large holes in the vehicle park area, on top of which were placed four field toilets, and these became our new toilet facilities. The field toilets were merely a plastic toilet seat with a large surround, which you placed over the hole and sat on. These were known as `go karts' as it looked like you were perched on one when you sat on it. It had a lid of course, but the whole area stank, especially as many of us were already suffering from running stomachs due to washing our greasy dishes in cold water and without soap. The toilets were entirely exposed, with no cover being placed around them, and it was in some way funny to see two or three guys at a time, sitting and chatting to each other while taking a leak or having a crap. It could be bloody cold in the dead of night though, and there was always the danger of a injudiciously placed footstep that might land you in the crap, literally!

At the same time as our toilets were taken off us, the showers were also banned, and we were ordered to wash in a fire bucket of cold water each day. This had to be done outside too, and completely naked. A water truck was brought in for the purpose, and we had to draw a bucket of water and then wash with half of it, using the second half to rinse yourself of as best you could. The results were inevitable, and another example of military stupidity.

One by one, men began reporting sick and being carted off to No.1 Military Hospital by the doctor, during his daily visits. I wasn't the first either, and by the time I fell ill, a couple of men had been to hospital and returned to us including one, Private French, who broke a leg during one of our afkak sessions.

My own illness came on very suddenly, and at the time I had no idea what was wrong with me. On 2 August, and only a few days before my 18th birthday, I began to feel feverish and listless. I wasn't coughing and had no difficulty breathing, so had no suspicion that I may have flu or pneumonia. At the time I put it down to a bout of diarrhoea I had just recovered from. I wasn't able to shake the feeling though, and shortly after lunch the following day I started vomiting violently, and couldn't keep any food down. I also was feeling decidedly crap by this stage, and one of the guys in my platoon, I think it was Dick again, called Corporal Steenkamp and told him that I was very sick. I was put to bed in the bungalow, where I shivered and burned up through the night alternately, and the following morning I stayed there, right through daily inspection by the Corporals. I still recall looking at Jordaan as he passed my bed, me too weak to even lift myself properly, and as he glanced at me he said, "Moenie vrek nie, Piela !" (Don't die, cock !).

After inspection, Dick and one other man were detailed to help me to the doctor's room, where he examined me and advised me that I was ill enough to need hospitalisation, and he would take me with him back to 1 Military Hospital once he was finished with the rest of his consultations. I could have told him that! As sick as I was, it was a tremendous relief to know I would not be doing basics for a few days, and I almost enjoyed the drive into Voortrekkerhoogte.

At the hospital, I was asked my next-of-kin details and told that a telegram would be sent to my parents, advising them that I had been hospitalised, and how they could contact me. This put my mind at ease, as I was concerned that they might not know where I was and panic when I didn't contact them. We had no telephones at Elandsfontein, and our only way of getting news home was via letters. Also, as family visits to Elandsfontein had been allowed on weekends from Saturday 29 July, my parents and fiancee Sharon might turn up at Elandsfontein to visit me when I wasn't there. As it was, my faith in the army's communication was misplaced once again, and the bloody telegram only reached them three days after I had found a phone at the hospital and managed to call them and let them know where I was.

On admission, I was moved to the lung ward, or respiratory ailments ward as it was officially known. It was quite a change from basics, as we got to lie around in bed all day. Many of the guys in the ward had pneumonia or bronchitis, most being National Servicemen like myself who had contracted their illnesses doing basic training. Some had other complaints, and were there mainly because there was no bed space available in their own wards and they were undergoing tests. Among the latter were an infantry Rifleman, Brian, who was suffering from bleeding abdominal ulcers, and a SAAF airman, Peter Rebelo, who had a suspected brain tumour, of all things! More on them in a minute though.

We were well looked after by a competent group of army nurses, all of whom were Afrikaans. To young National Servicemen they looked like angels in white, and we were always chiding them about boyfriends, or their looks. Nowadays it would be called sexual harassment, but they never complained and skilfully avoided our questions or pulled rank on us when we became insistent. The ward sister, a beautiful young blonde woman who looked about 24 years old, was a full Lieutenant, and kind to a fault. She was firm though, and used to insist that we got up and remade our beds each morning if we were well enough to do so. Those who were not, had their beds made for them by the nurses.

When I first arrived, I was in pretty poor shape and slept most of the time, day and night. Nobody told me what was wrong with me, but I was visited by doctors and put on a regime of strong antibiotics and given vapour therapy of some kind. For the latter I had to go to a special room, where I was hooked up to a vapour making thing via a mask, and I had to breathe the steam for about 30 minutes at a time. After that I received a vigorous massage of my lungs via my back, which was painful and caused me to cough up the most ghastly stuff, but I did feel that I could breath easier afterwards.

On the weekend of 5 and 6 August, my fiancee Sharon and my parents visited me in the hospital and it was great to see them again. In fact, while I was in hospital they visited me faithfully, which was bloody good considering I was in Pretoria and they lived in Johannesburg. I am still embarrassed today by my churlish behaviour on my 18th birthday, 10 August, when my mother called to visit me but Sharon didn't. I was less than gracious and managed to annoy my mother considerably with my petulance at Sharon's non arrival. It was ridiculous of me to expect her to turn up on a weeknight when she was working (it was a Thursday) and equally ridiculous to expect my mother to know why she wasn't there. My mother had come to see me from Johannesburg, after a full day's work herself, and I never gave her the acknowledgment and thanks she deserved for that at the time, as I was very happy to get a visitor on my birthday. I hope I have learned to be more gracious since then!

After I'd been in the hospital for a week or so, I had made firm friends of the infantryman, Brian and the SAAF airman, Peter. In Brian's case, he had been in hospital for at least two weeks before I arrived, and had been rushed there from 4 SAI in Middleburg with the aforementioned bleeding ulcers. These proved to be so bad that he had 80 percent of his stomach removed surgically in an emergency operation, to prevent him bleeding to death, and he was in the process of adjusting to life with the smaller stomach, eating smaller meals more frequently etc.. He firmly blamed the army for his predicament, and at the time I wrote to my mother and said I didn't know why he did so. Now I'm pretty sure he was right! His ulcers were almost certainly brought on by a nervous disposition, as he was quite a jumpy little guy, as I recall, and the infantry training was tough.

To add to poor Brian's woes, while I was at the hospital still, they discovered that he had a much enlarged liver too, his liver being three times the size it should have been, and I never did find out what the latest thing was, as we lost contact after I was returned to my unit. I sometimes wonder if he is still alive today, as he was only 18 at the time and these were serious complaints.

My other mate in hospital was Peter Rebelo, from the Air Force Gymnasium in Pretoria, who had been diagnosed with this brain tumour of sorts. They still were uncertain whether this was malignant or not, and he was undergoing tests. We used to spend a lot of time talking to one another and I found him to be quite an interesting character. A National Serviceman like myself, he had been in the SAAF since January. While they were still trying to determine the extent of his tumour, he lapsed into a coma, and the army were forced to perform brain surgery to remove it. This was towards the end of my stay in hospital, and it was quite a shock to wake up on the morning of 16 August and find his bed empty. I asked if he'd been discharged, and was told he was in emergency surgery instead!

Following his surgery he was placed in Ward 2, which was where all serious injuries and post surgery cases went, and Brian and I visited him there in the evening, following quite a few hours of serious surgery. We found him quite weak and still bleeding through a massive bandage that swathed his head. Fortunately, the tumour turned out to be benign, and the surgeons had removed all of it. Sadly, it was not the end of Peter's problems. I kept in touch with him after we had both been discharged from hospital, and learned that he had been granted a permanent discharge on medical grounds. He returned to civilian life, and made a new start, only to suffer a black out one day while driving his car. In the resultant crash he killed someone in another vehicle, and promptly lost his licence, as they could not let him drive while he was having black outs. These became more frequent, and it was shortly after he had written to me of this, that I lost contact with Peter altogether. I hope he made a complete recovery eventually.

Peter's misfortune also gave me my first disturbing glimpse of the border war, then being fought in far away South West Africa. It was barely mentioned in the media at this time, but everyone knew it was happening. On visiting Peter though, I found Ward 2 to be full of men who were recovering from wounds received on active duty in SWA, including amputations from anti-personnel mine injuries and gunshot wounds. I didn't fraternise with these men, as I was somewhat awestruck by them, little realising that many were young National Servicemen like myself. They all looked so old and worldy wise, a look I was to see again during my two years National Service.

The wounded also brings to mind another piece of stupid military thinking. Directly opposite Ward 2 was Ward 1 - the permanent force maternity ward ! What all these women thought, on arriving to have their babies, only to be confronted by the badly wounded soldiers emerging or going into the ward opposite their own, I can only imagine!

Although the doctors had hoped for a swift recovery for me, it took two weeks before I was fit to be discharged, as x-rays continued to show infections in my lungs, the right one only clearing up just before I was discharged on 18 August.

I had made good progress after being initially admitted to hospital, but had a relapse of sorts and I recall waking up one particular morning, only to discover that it was way past breakfast time and I had missed it. I was disappointed and rang for the young duty nurse, who promptly rushed over with a seriously concerned expression on her face, and asked if I was alright! I was puzzled, but said I felt OK, and she then told me I had been seriously ill during the night, feverish and hallucinating, with an ugly cough thrown in, and she had felt compelled to call the duty doctor for me at some very early hour, as she feared for my safety. I knew nothing of it, and just felt as if I had enjoyed a decent night's sleep! Evidently the doctor had been concerned enough to ask for hourly updates through the night, and had also given me an injection of some sort, all of which I was blissfully unaware of. The rest of that day I was made to stay in bed and the nurses made my bed for me when necessary - quite nice really!

Return to Elandsfontein

All good things come to an end, and I was discharged on 18 August, and returned to Elandsfontein, being picked up by the supply truck that went there occasionally from Services School. Initially I was placed on light duty, as my illness had been quite bad really, and the doctors were well aware that I was returning to my unit to complete my basic training.

As it was, my return was marked by more surprises, some pleasant and some not. The best news was to be told that, during my absence, Corporal Jordaan had been arrested, and was in detention barracks (DB)! I wish I had been there to witness it, but as I wasn't I got the full story from my mates.

It seems that he was physically abusive to one of the platoon once too often, and was caught out this time. The unfortunate recruit was Private Leslie Bromilow, whom I had actually known since school, although he wasn't a close friend. Les was in our platoon and evidently Jordaan came around one evening, as he was wont to do, and threw his weight around, as well as a few beds. When he came to Les Bromilow, he was really throwing his weight around and he smacked Les on the shoulder very hard with his swagger stick, which all of our Corporals had. Jordaan, having finished his tirade, stormed out of the bungalow, leaving Les sitting on his bed in a lot of pain and very distressed. His shoulder very quickly swelled up and he could barely move his arm.

While I was in hospital we had also acquired two new officers at Elandsfontein, both Second Lieutenants and both National Servicemen. They were Lieutenant Swart, who was to become the Company 2IC, and Lieutenant Krige who, despite his name, was English speaking rather than Afrikaans. Both were from the PSC rather than ASC, and why they had been sent to Catering School, which was an ASC camp, is anyone's guess.

Private Les Bromilow

Anyway, to return to Jordaan and Bromilow, Lieutenant Krige happened to visit our bungalow shortly after this incident took place, and found Les in his distressed state. He looked at Les' badly bruised shoulder and asked him who had struck him, but Les didn't want to answer as he feared reprisals from Jordaan. Dick came to his rescue and told the Lieutenant that Jordaan had struck Les with the swagger stick. Lieutenant Krige promptly had Jordaan arrested, and drove with him to the DB in Voortrekkerhoogte, even though it was evening and most places were closed. Once there he had Jordaan processed and locked up for striking a junior rank.

The upshot of all this was that Jordaan was formally charged, court-marshalled and just escaped being reduced in rank. He received a suspended sentence and a severe reprimand, and was warned that any repeat would see him reduced to the ranks and doing time in DB. It certainly changed his behaviour toward us as, like the bully he was, he'd had the stuffing knocked out of him by being arrested and threatened, and although we still occasionally received punishment PT from him, he never laid a hand on one of us again. I still think it's a pity they didn't shoot him, as he certainly deserved it!

My return to Elandsfontein also brought me more trouble, as I failed my first uitpak inspection on 23 August, as some twit in my platoon had spilt syrup from a hastily made sandwich right next to my bed, and I'd not noticed this. I was dragged in front of the Lieutenant and for my `crime', was given three 40 minute periods of corrective training (afkak)! I hadn't even spilt the bloody syrup there in the first place. Luckily I was still on light duty at the time, so was not able to do them right away, as any form of physical punishment was strictly prohibited while on light duty. It didn't save me from eventually being run ragged though.

To top off my misery at the time, I had my first weekend leave pass cancelled for some other indiscretion, although I cannot remember now why. Semi regular leave passes had been issued from the weekend of the 11th August, while I was in hospital, and half the Company went on leave each weekend, with the other half being released the next weekend, and so on. I had missed out on the initial couple of weekends due to being in hospital, and now to have my first weekend pass cancelled was almost unbearable. In fact, I was not to get any leave home until the beginning of September.

Target practice and other forms of afkak

Although chefs, we were still required to do basic infantry training and learn about rifles, in case we ever needed to shoot somebody (I could have thought of a few people who deserved shooting, but none of them were enemies!). Our first trip to the shooting range at Voortrekkerhoogte was interesting, but potentially dangerous and bloody bad luck for some of the guys. We were collected by a load of Bedford trucks from Services School, and driven out to the range, where we were arranged in our platoons. We'd already been given detailed instruction of disassembling, reassembling and cleaning our R1 rifles, during our daily lectures, but to date we had not fired them.

I won't go into details of my own experiences on this first occasion, as I was fortunate enough not to earn the wrath of any of our NCO's who conducted the shooting. I'd never fired a rifle before, apart from an air rifle as a child, so had no idea what it would be like. We were issued with the exact ammunition we would require for each section of the target practice, for example ten rounds rapid fire, in which the target was popped up for a few seconds by a fellow recruit behind the fire wall, and you opened fire on it from the line 100 yards away, one round at a time, until your ten rounds were finished. You had to fire off all ten rounds too, as not to do so was considered to be a very serious infraction and subject to immediate punishment. You still had to aim and your results were assessed by the person operating the target. This went on, firing slow and rapid, from kneeling and prone positions, from distances of 100 metres, 200 metres etc..

I found the whole experience exciting, but my shooting was hopeless, and although I cannot recall my score for the entire exercise, I was one of the lesser lights. This can be partly explained by my rifle's sights not having been properly adjusted, which was a common problem with these recruit rifles issued to us. We complained, and one of our Corporals, who had his sharpshooters badge, fired a series of rounds at the target with a borrowed rifle. Even he couldn't do very well, only scoring with about 60 percent of his shots. One or two of our guys did well though, enough to qualify for their sharpshooter badges.

That first experience of shooting a rifle was an eye-opener. The noise as the rifle fired seemed deafening with a whole ragged volley of shots going off down the line, and those of us injudicious enough to grip the rifle too tightly got a hell of a kick in the shoulder and cheek from the recoil - yes, I was one of them. We soon settled down though, but God help the roof who failed to follow the Corporals' instructions, as for them the dreaded ammunition cases waited. For anyone stupid enough to still have ammunition in his rifle after a shooting exercise, especially in the chamber, would be given one of these full cases of 7.62 mm ammunition, which weighed a ton, and made to run around the range, usually until they dropped and could not do so any longer.

The worst punishment dished out that day, for the worst infraction, was to poor Les Bromilow again. We had just fired off ten rounds rapid fire from a prone position and a range of 200 yards. We were then ordered to stand ready for the Corporal to walk down the line and inspect our rifles. The way this was done, was you held your rifle, barrel pointed down at an angle, with your breach block open to show that there were no further rounds in the rifle. You also removed your finger from the trigger and trigger guard completely.

If you emptied your magazine in the R1, the breach automatically stayed open, ready for you to cock it again once you'd loaded a new magazine into the rifle. If, however, you had not fired everything off, the breach would be closed as the semi automatic action would pop the current round from the magazine into the chamber and the breach closed, ready to fire straight away. Les was standing a few men down from me, rifle facing down as we had been told, but he hadn't noticed that he had not fired all ten rounds and had a round in the chamber. We were supposed to count our shots as we fired them.

As the Corporal approached from the right and in front, checking each man's breach block in turn by glancing at it as he passed, we had our rifle barrels turned slightly away from him, just in case. He was approaching Les when the latter, no doubt nervous, squeezed the trigger on his rifle - BANG ! - his cocked and loaded rifle fired, the round kicking up a puff of dust about four feet in front of the approaching Corporal as it slammed into the ground. We all just about died of fright in the immediate vicinity, and the Corporal's reaction was immediate and extreme. He rushed Les and slammed him to the ground, screaming obscenities at him as the other Corporals and Sergeant joined in. I honestly thought they would kill him but sanity prevailed. It was the last shooting Les did that day though, as he was loaded up with an ammunition case, and hounded around the range for the rest of the morning, eventually collapsing in a heap when he could no longer run. His crimes, for they were many, were not firing all his ammunition off, not counting his shots and having his finger on the trigger during rifle inspection. He wasn't the only roof punished that day, but his was by far the worst.

As a whole, we looked upon our rifles as something of a curse during basic training, as we were often given rifle PT with the damned thing, and it was the cause of many a failed inspection. Rifle PT was a particular torture, and involved holding your rifle in various unnatural poses until every muscle in your arm or arms holding the rifle would be screaming in painful protest. For example, on one occasion at Elandsfontein we were made to stand to attention and hold our rifles with straight outstretched arms for ten minutes, after which it felt as if my arms would never unfreeze again, and the pains were shooting all the way down my back and legs. We were also given no ammunition for the damned things, which was probably just as well, in hindsight!

Home at last

Finally, on 1 September, my name came up for a weekend leave pass, and it was with great excitement that I greeted the news, as I was one of the last men in the Company to be granted leave, due to my earlier stint in hospital and then having my only other leave pass confiscated for some infraction.

The ritual with regard to weekend leave was that we had our usual daily routine, but in the late afternoon, instead of having PT, those of us going on leave would be excused so that we could shower and dress in our full dress uniforms, which were worn on these occasions. Once we had done so, we had to form up in a squad for inspection, and if we passed this last step satisfactorily, we were handed our leave pass books, with our absence period duly noted therein (usually from 4 pm on Friday to approximately 9 pm on Sunday) and dismissed.

Then came the fun part, trying to get home! This wasn't as difficult as it sounded, as soldiers were so plentiful then that everyone knew one, and passing motorists were quite willing to pick us up and give us a lift if we were in uniform. In our case at Elandsfontein, we had a fairly long walk from the camp to the main road, but I never had a problem doing so when I was going on leave! It took about half an hour to get to the main road if you walked, and then we headed either west or east, depending on where you lived. In my case, it was always east, away from Pretoria, as I could get a lift out towards a nearby crossroads, and from there hitch hike south, getting to Johannesburg through the back route, via Halfway House and Bryanston. Lifts were that good that we were frequently at home by 6 pm, despite the distance, although I was a little later than this on occasion.

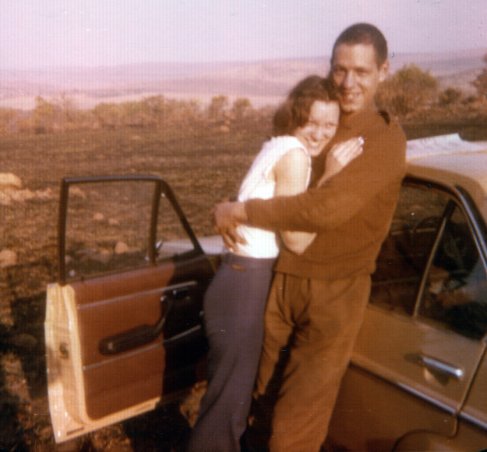

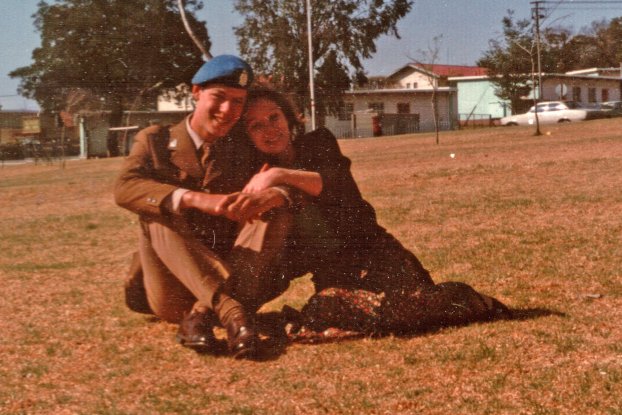

At home on weekend leave in September 1978.

That first weekend pass was wonderful, as it was my first taste of all the things that had been familiar to me before I had been to the army. I got to see my future in-laws again for the first time in two months, and actually see everyone in a more relaxed and private environment. There were the usual oohs and aahs, about the handsome young man in his uniform, and I think I had more photographs taken of myself on that one weekend than at any time in basic training. I didn't own a camera and we were forbidden to have them on us anyway, a restriction that was even more enforced in South West Africa, while on operational or semi-operational service. It didn't stop people from having cameras though, and using them, as I later did acquire one and snapped away happily, although I wish now in hindsight that I'd been a bit more discriminating in the things or people I did photograph. More of that later though.

At the end of my first weekend pass, my father drove me all the way back to Elandsfontein, so that I arrived there just before 9 pm. This was a real sacrifice as it meant he lost his entire evening off by the time he'd driven me out there from Johannesburg, and returned home, and he had an early start for work the next day. Right through my time at Elandsfontein, my parents would insist on driving me back to camp each Sunday when I had been home on leave, rather than have me risk the uncertainty of hitch hiking back.

By early September our fitness training and afkak was also taking on more of a Company feel than a platoon one. We would usually all be lined up, given instructions and split into squads based on our height and physical prowess, and then off we would go. I am fortunate in being able to use old letters, written to my mother, as well as my own recall, to provide details of some of these.

For example, on Monday 5 September we were split into four large squads after lunch, and each squad was given a metal dustbin, ⅓ filled with sand, two steel fire buckets, also filled with sand, and a huge tractor tyre. We were then taken on a five kilometre run in which we had to, as a squad, ensure that all the items completed the trip with us, and without spilling any of the sand either! I remember that trying to transport the tyre, either by rolling it or trying to carry it, was a nightmare and I was completely stuffed by the end of this particular exercise. We were then horrified to be told to report for PT when we got back to camp! We all did so of course, but the PTI chased us around the water tower once and packed it in for the day. I think he could see how stuffed we were.

Another favourite, mentioned earlier, was pole PT. This could be individual, using a pole stump, or collectively, with a group of six or eight men being allocated to a wooden telephone pole. The poles were heavy, and awkward to carry as you had to hold them on your shoulder, and every time you took a step while running, the pole would whack you in the shoulder. To try and alleviate this, we always used to take off our PT shirts or singlets and use these as a sort of cushion on our shoulder that was supporting the pole.

On one occasion the group of guys I was with, all tall and of reasonably uniform height, had Private French added to our group. Frenchie, as he was called, was a short arse and in no way of comparable size to the rest of us, and I think the Corporal just added him to our squad to make our lives difficult. When running he couldn't reach the pole we were balancing on our shoulders, but the Corporal insisted he be part of the group and attached to the pole, like the rest of us. So, he made Frenchie hang off the pole using his arms, making the rest of us run with not only the weight of the pole, but Frenchie too! Despite the Corporal's efforts to scupper us though, we still finished first on this occasion, our incentive being that all the guys doing pole PT in that exercise were going on weekend pass, and could leave as soon as they got back to Elandsfontein with their poles, then showered and dressed in their uniforms for leave parade.

Jackals, snakes and other creepy crawlies

The South African veld abounds with various nasties, such as snakes, scorpions, spiders and rats - not to mention the Jackals at Elandsfontein, which could be heard howling and barking to each other through the night. The latter were harmless enough to us, being of a shy and cowardly disposition, but it was still spooky to see their eyes glowing in the dark, just outside the camp lights.

The snakes were very abundant, and we were coming across them all the time. In my own case, I had a very close shave with a potentially lethal one, which Sergeant Janse van Rensburg saved me from. The Company was lined up in front of the Lieutenant's office just after lunch, and the Sergeant called me over to move a hosepipe that was lying coiled up on the small patch of grass in front of the office. Luckily the Sergeant was standing right there as I bent down on my haunches and lifted the hosepipe. As I did so a snake, that had been sleeping either under or inside the coiled hose, reared up in fright to strike me. Equally frightened, I stumbled backwards onto my backside but even as I did so, the Sergeant reacted instantly and stomped on the snake with his boot. Its thoughts promptly turned to escape but he continued to stomp on it until it was dead, throwing the now smashed snake away with a look of disgust on his face. I just sat there like a stunned mullet!

I do recall that one of our PTI Corporals liked to collect live snakes, captured in the surrounding bush, which he would place in cloth sacks and hang in the sun, on the fence surrounding the camp. There the unfortunate snakes died of heat exhaustion and starvation, rather barbaric in hindsight but we really didn't care about them at the time. He told us he took them home to his mum!

Another time I had gone with a driver into Services School at Voortrekkerhoogte, to collect some supplies. We were driving back to Elandsfontein, having already turned off the main road and onto the dirt road which led to the camp, when we came barrelling around a bend in the road - and saw a very big Black Mamba crawling across the road in front of us. The driver put his foot on the accelerator and we drove straight over the snake. Thinking we'd killed it, we looked back as we drove on, and saw the very angry snake rise up with its hood in threatening pose, glaring at us, or so it seemed. Boy, that snake was tough!

In October we even had one crawl right through our bungalow, in broad daylight, and one of the men tried to grab it by the tail! Rather than bite him, which he really deserved for being so bloody stupid, it just wriggled free and took off as fast as it could crawl. That same month myself and three other men found one while moving some rusty machinery that had been stored against the fence on one side of the camp, and we smashed this one's head in too, as it was a venomous snake.

The Scorpions, although less of a problem as they tended to hide under rocks, also had to be watched out for, especially when we were out in the bush doing infantry work, which on a couple of occasions would mean sleeping in the bush overnight. Scorpions hunted at night often, and I was always concerned I'd find one in my sleeping bag with me.

Infantry afkak outside of camp

As part of our basic infantry training, we were taken out one day on a route march, in full kit. All we were told was to tree aan (fall in) in full kit with rifle and helmet, and once we had done so, away we went. We marched at fairly brisk pace until we were well clear of the camp, and then we were put through a series of exercises, such as infantry attacks and leopard crawling to an objective.

After we had been at this for what seemed like hours, but was probably only two hours at most, we reached the river, which flowed along near the main road. Here we were confronted with a rope, suspended between two trees over the river. We were informed we had to cross the rope bridge, in full kit and with our rifles, and then were given a demonstration by one of our Corporals, who had neither full kit nor rifle encumbering him when he did so! The best way was to get on top of the rope and lie with your feet crossed over the rope behind you, and your arms in front, rifle cradled in them, then pull yourself along and pray you didn't over balance! Many did, and either clung on for a short time, then fell in the water, or fell straight in, encouraged by the odd thunder flash thrown in the water by our Corporals, to simulate enemy gunfire! I was lucky; I got across without falling in, merely getting my feet wet right at the end because I mistimed my leap from the rope and landed just in the water. The unfortunates who fell in were soaked, and night was falling by this stage.

We eventually began to wonder when we were returning to camp, as night had fallen, but our hopes were soon dashed when we were ordered to make camp and defensive positions, and cans of food were distributed. For the latter, we were given three tins between three of us, which we had to open with bayonets and eat as best we could. Each can had different contents, so one man would eat his share, pass on to the next man, and then the last man would finish the can off. We were so hungry and tired by this stage that we didn't care!